Murals are large works of art painted on fences, walls and sides of buildings. Northern Ireland has around 2,000 murals, most of which contain political themes or references to the Troubles. The largest concentration can be found in Belfast – the capital boasts at least 700 murals, a third of which are in excellent condition. Other locations with prolific muralling include Derry, Newtownards, Bangor, Carrickfergus, Portadown, Newry, Ballymena and Enniskillen.

Northern Ireland’s political wall art dates back to the early 20th century when it was used occasionally by Loyalists. The late 1970s and 1980s saw an explosion in muraling as a form of political expression. Some murals were created by artists commissioned by political or paramilitary groups, others by amateurs unknown to history. One notable group of muralists is the Bogside Artists, a trio of painters from Derry. Beginning in 1993 the Bogside Artists have created numerous murals about the Troubles, including the famous ‘People’s Gallery’ in Derry’s Rossville Street.

Ideas through imagery

The content of Northern Ireland’s murals varies, depending on the artist and where they are located. Murals in Catholic areas naturally reflect Nationalist views and values. They celebrate Irish culture or symbols, refer to particular incidents, pay tribute to martyrs like Bobby Sands or commemorate innocent victims of the Troubles. Loyalist murals use British or Loyalist symbols and colours, contain historical or traditional references, or honour paramilitary volunteers and units.

Some of these murals – with their ‘guardian figures’ wearing camouflage, balaclavas and brandishing weapons – can seem intimidating or confronting to outsiders. Some murals contain no political or sectarian themes at all. Instead, they promote peace or depict foreign leaders like Nelson Mandela, writers like C. S. Lewis or footballers like George Best.

Many of Northern Ireland murals are obvious political propaganda but they also stand as historical evidence, telling a story that cannot be ignored. The people of Northern Ireland understand the importance of their murals and have worked to preserve and maintain them.

Today, these murals, along with peace walls in interface areas and the occasional checkpoint, are the most visible remnants of the Troubles. Thanks to their artistic merit and historical value, the murals have become an important tourist attraction in post-Troubles Northern Ireland. Some prominent examples are discussed below.

Tributes to victims

Annette McGavigan was a 14-year-old resident of Bogside in Derry. In September 1971, the area was hit by sustained rioting. McGavigan stepped outside during a lull in the violence, possibly to collect items for a school project or to gather spent plastic bullets (a common childhood pastime during the Troubles). In the street, McGavigan was spotted by a nearby British soldier, who suspected she might be planting a bomb. He fired a single shot, hitting Annette in the back of the head and killing her instantly.

A mural dedicated to Annette McGavigan can be found on Rossville Street, Derry. Titled “Death of Innocence”, this image serves several purposes. It commemorates an innocent victim and hints at the heightened tension and paranoia among British soldiers in Ulster.

The chaos and shattered structures in the background suggest the aftermath of a bomb explosion, a reminder of violence once common in the area. McGavigan appears in school uniform to emphasise her youth. The rifle beside her is broken, a hopeful sign that the violence has now ended. Above McGavigan’s head is a brightly coloured butterfly, a symbol of beauty, hope and rebirth.

‘The Hunger Strikers’

Also located on Rossville Street is ‘The Hunger Strikers’, a mural dedicated to Raymond McCartney and his fellow prison protestors. McCartney is a Derry-born Catholic who joined the Provisional IRA after his cousin was shot dead on Bloody Sunday. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1977.

In October 1980, McCartney and several other Republican prisoners began a hunger strike, demanding the return of Special Category Status (SCS) for Republican paramilitary prisoners. McCartney went for 54 days without food and was close to death when the hunger strike was called off in December.

The Rossville Street mural shows McCartney as gaunt and emaciated. The background is a contrast of stone prison walls and open skies. The mural also depicts a female hunger striker in Armagh Women’s Prison, a group seldom mentioned in historical accounts.

Loyalist tributes

The mural of Loyalist volunteer Stevie ‘Top Gun’ McKeag on Hopewell Crescent, off Shankill Road, is typical of individual memorials. McKeag was a member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and its paramilitary wing the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). Active from the late 1980s until his death in 2000, McKeag was responsible for multiple murders. One of his victims was Lawrence Murchan, a 63-year-old shopkeeper who was the 2,000 person killed in the Troubles. McKeag is rumoured to have been involved in the 1992 murder of Philomena Hanna, a Catholic chemist’s assistant who delivered prescriptions to the elderly, including many Protestants.

Loyalists named McKeag ‘Volunteer of the Year’ several times, a decision that may have fuelled resentment among his fellow volunteers. He was found dead in September 2000, most likely from a drug overdose.

The Hopewell Crescent features a portrait of McKeag surrounded by Loyalist flags (the Union Jack and St George’s Cross), UDA and UFF logos and the silhouettes of two volunteers resting on arms. An interesting aspect of Loyalist murals of this kind is that in recent years they have become less confrontational and provocative. Recently, McKeag’s mural has been updated to photographic transferred boards in order to protect it from the elements.

William of Orange

Murals featuring William of Orange, later King William III, can be found scattered around Protestant areas of Belfast.

William (1750-1602) was a Dutch-born Protestant prince who became King of England in 1689. In doing so, he expelled the Scottish Catholic James II from the throne. The following year, William sailed to Ireland where James and his supporters, dubbed the Jacobites, continued to resist his rule.

William’s forces defeated the Jacobites at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. This victory of Protestantism over Catholicism is commemorated by the Orange Order and other Protestant groups in Northern Ireland. The anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, July 12th, is the pinnacle of the Protestant marching season. Many Loyalist murals feature portraits of William, references to the Battle of the Boyne or orange flowers, a nod to William’s Dutch homeland. The mural pictured is located at the corner of Sandy Row and Linfield Road.

Free Derry Wall

Free Derry Wall is a sign rather than an artistic mural. Despite this, the wall is one of the most recognisable visual symbols of the Troubles.

Free Derry Wall can be found in Bogside on the remains of 33 Lecky Road, a house that once served as a gathering place for political meetings. The house is gone but the wall and its sign remain as a symbol of Nationalist defiance. This corner became a common meeting place or rallying point during the Troubles.

The Free Derry Wall slogan was first painted amid violence that erupted after a People’s Democracy march in 1969. Today, the Wall serves as a blank slate for various issues and causes and is frequently repainted. Its colours have been adapted to reflect global issues like the struggle of the Palestinian people, with whom Irish Nationalists have often identified (see picture). The wall is used to protest other issues or to celebrate or promote events in the local community.

The Falls Road murals

Several community-based art projects in Northern Ireland have helped bridge the divide between Catholic and Protestant communities. Perhaps the most visible can be found on the Lower Falls Road, where a series of murals adorns walls abutting the street.

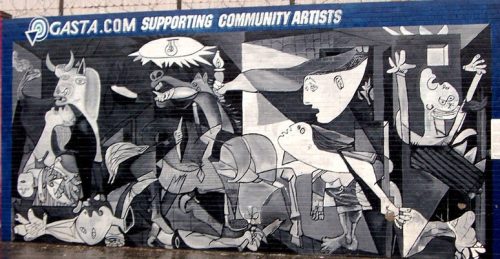

In 2007, Catholic artist Danny Devenny and Loyalist Mark Ervine joined forces to produce a replica of Guernica along the Falls Road. Painted by Pablo Picasso in 1937, Guernica depicts the bombing of a market town during the Spanish Civil War.

Though inspired by a foreign conflict, the deadly mayhem in Guernica certainly resonates with the people of Northern Ireland. Devenny said that while he and Ervine held fast to their political views, both found they had much in common and their collaboration was a success. In recent times the focus of Northern Ireland’s murals has embraced internationalist perspectives. Murals on the International Wall, for example, express sympathy and solidarity with other nationalist movements, such as the Palestinian people.

Recent transformations

In recent times, the face of ‘conflict art’ in Northern Ireland has evolved and softened – evidence of healing communities and a firming peace process.

This is particularly apparent in Belfast’s traditional Loyalist areas, where murals like the charging skeleton in military garb have been removed and replaced by community-based images such as the “Women’s Quilt”, a patchwork of images depicting the importance of women and family in the Shankill area.

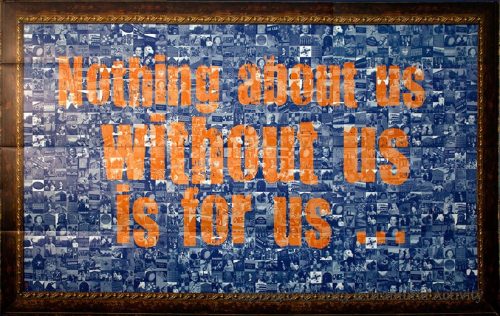

In a more political vein, the old Malvern Arch artwork – a Loyalist mural depicting a rallying point for Orangemen on July 12th – has been replaced by the Hopewell Crescent mural (pictured). Formed from a mosaic of pictures of local people and scenes, the Hopewell mural spells the slogan “Nothing about us, without us, is for us” – a reflection on the importance of community, whatever the political landscape.

Remnant sectarianism

These changes are neither absolute nor permanent. Eagle-eyed observers will note that alongside these new neutral, conciliatory murals sit framed images of the more controversial pieces they have replaced. Some interpret this as a careful cataloguing of art and history, to avoid whitewashing the past. Others consider it a stubborn grip on old ideas and values, a reminder that sectarianism is not dead and that peace may not be forever.

Murals are not the only new artwork appearing in Belfast. In the same Shankill estate stands a new sculpture, commissioned by the Arts Council’s Re-Imagining Communities Fund. It comprises three steel pillars bearing the words “Remember”, “Respect” and “Revolution”, each letter hollowed out to allow the sun to stream through. These newer pieces seek to break the cycle of violence by replacing more provocative art and its influence on the young.

Community has also become a focus in Derry. Within the Bogside, once the scene of horrific army violence and Republican paramilitary activity, a new platform sculpture depicts the changing nature of Derry streets – from the turn of the century to the modern era.

© Alpha History 2019. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole and S. Thompson, “Northern Ireland murals”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/northern-ireland-murals/