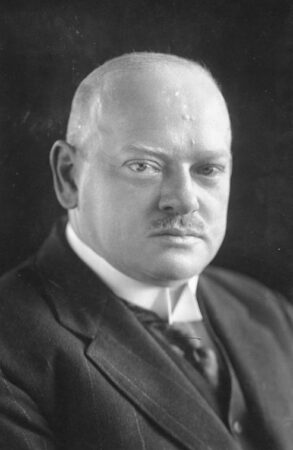

Gustav Stresemann, who served briefly as chancellor and then as foreign minister for most of the 1920s, was arguably the Weimar Republic’s greatest statesman. Unlike many of his fellow Weimar politicians, Stresemann demonstrated a thoughtful pragmatism, a passionate but rational nationalism and a capacity for getting things done. These qualities may have helped Germany endure the rocky political and economic waters of the early 1930s. As it was, Stresemann’s premature death in 1929 robbed Germany of one of the few political leaders not mired in self-interest, partisanship or extremism. Stresemann’s departure coincided with and perhaps opened the gates for Germany’s descent into dictatorship and totalitarianism.

Born to a middle-class Berlin family in 1878, the young Stresemann was a talented student who excelled in the arts, literature, economics and political studies. He entered politics, standing as a National Liberal Party candidate in Saxony. In 1907 he became the youngest member of the Reichstag, aged 28. By 1917 Stresemann’s political talents had propelled him to the party leadership. At this point in his career there was little to differentiate Stresemann from other nationalist reactionary politicians. A fervent monarchist and nationalist, he was firmly committed to the war effort. When the National Liberal Party began to dissolve in 1918, Stesemann joined the newly-formed German Democratic Party (DDP). But his nationalist views placed Stresemann in the right-wing of the liberal-centrist DDP, and he soon became disenchanted with the party’s program. By early 1919 Stresemann and several colleagues had abandoned the DDP and formed their own party, the Deutsche Volkspartei (DVP, or German People’s Party). In April he explained his vision for the DVP: “We are on course to become the old ‘middle party’ which is indispensable to the life of the state”.

The Treaty of Versailles heightened Stresemann’s nationalism. He cursed the treaty as a “moral, political and economic death sentence” for Germany; labelled the League of Nations “a farce, an American-English world cartel for the exploitation of other nations”; and condemned Weimar politicians like Ebert for believing the “foolish dreams” that Germany would be treated fairly by the Allies. Through mid-1919, Stresemann lobbied against the Reichstag’s ratification of the Versailles treaty (it was passed 237 votes to 138). In August 1919 Stresemann reasserted the nationalist view that Germany must work to restore her strength:

We are united that we must again attain a respected position in the world, and this goal can only be achieved by strong leadership. We will not be deceived by talk of a ‘League of Nations’. Already we see the triple alliance of Britain, America and France… what is this except a return to the old system. Our views have already been proved more right than even we anticipated. There will be powerful alliances again in the future, and the task for us is to become alliance-worthy again.

In the early 1920s, however, Stresemann’s nationalism began to dilute as his politics shifted towards the centre. Historians have pondered the reasons for this change in Stresemann’s outlook. Some suggest that Germany’s economic turmoil in 1922-23 convinced him that recovery was impossible without international co-operation. Stresemann was certainly disillusioned by the militant nature of German nationalist movements: he thought that reform rather than revolution was the best way to secure Germany’s future. Stresemann disapproved of both the failed Kapp putsch (1920) and the NSDAP’s Munich putsch (1923). He was also alarmed by right-wing political violence, especially the assassinations of Matthias Erzberger (1921) and Walter Rathenau (1922); though Stresemann had his share of disagreements with both men, their murders appalled him.

“With the possible exception of Aristide Briand, no figure since the war has so dominated European affairs as did Herr Stresemann; and no statesman has shown so unwavering a devotion to what he conceived to be the right course for his country. By a fortunate coincidence, it was also the right course for the world. Herr Stresemann may be said to have been the first of the Europeans.”

J. Wheeler-Bennett, historian

By 1922 Stresemann was working more closely with moderate and left-wing members of the Reichstag. In August 1923, chancellor Wilhelm Cuno was forced from office and Stresemann was invited to replace him, leading probably the broadest coalition government of the Weimar period. The ongoing occupation of the Ruhr, the spiralling hyperinflation and the weakness of Stresemann’s coalition doomed his government to inevitable collapse. But he did not shy away from making some difficult decisions, calling a halt to ‘passive resistance’ in the Ruhr and giving the Allies a commitment to restoring Germany’s reparations instalments. This did not mean Stresemann had changed his view of Versailles – he still loathed it and hoped for a revision of its strict terms. But he believed the best way to facilitate this was to abide by the treaty and begin negotiations with the Allies in good faith.

These measures were ultimately successful but they made Stresemann unpopular across the political spectrum. The Social Democratic Party (SPD), the architect of ‘passive resistance’ in the Ruhr, opposed Stresemann’s cancellation of it; the SPD would eventually withdraw from the Stresemann coalition. This forced Stresemann’s resignation as chancellor on October 3rd, though Ebert had little option but to reappoint him two days later, this time with a much thinner coalition. Nationalists were also incensed by Stresemann’s preparedness to co-operate with the Allies. On October 21st, separatists in the Rhineland – who considered the Weimar regime “spineless” and incapable of protecting their interests – attempted to establish their own republic. This was followed a fortnight later by Adolf Hitler and the NSDAP’s ambitious attempt to seize control of the Bavarian government in Munich.

Though both putsches were unsuccessful, they cast a shadow over Stresemann’s cabinet. Stresemann himself chose not to take strong action: he had a low regard for political fringe groups like the NSDAP and considered their putsch a relatively minor incident. But others in the Reichstag were more concerned about the increase in ultra-nationalist activity under Stresemann’s watch. By late November, the chancellor was facing a no-confidence vote in the assembly. He resigned the chancellorship on October 23rd, this time for good.

Though gone as chancellor, Stresemann remained as foreign minister in the newly formed government of Wilhelm Marx. Stresemann continued his political pragmatism in this role, forging reconnections with Germany’s European neighbours, restoring diplomatic ties and seeking international support (see Foreign relations). In August 1928 Stresemann’s work was interrupted by a small stroke, suffered during a party meeting. He took no time off but while his mind remained keen, Stresemann’s essential skills – reading and writing – were noticeably affected. He died in October 1929, aged 51, after another much larger stroke. The European press hailed Stresemann as a hero, a man befitting the ‘new Germany’. The London Times wrote of him:

“He remained intensely nationalist, but the necessities of Europe … led him to the wider nationalism, that sees co-operation as the only escape from chaos… It is intelligent and practical patriots – not vague idealists – who make the ‘good Europeans’ of today. Stresemann did inestimable service to the German Republic. His work for Europe as a whole was almost as great.”

1. Stresemann began as a right-wing politician: nationalist, monarchist and vehemently opposed to the Versailles treaty.

2. His position moderated in the early 1920s, as he worked in coalitions and spurned political violence.

3. Stresemann was chancellor briefly in 1923, ending passive resistance and implementing fiscal reforms.

4. As foreign minister, he worked to restore good relationships with Europe and revise the Versailles treaty.

5. Stresemann’s pragmatic approach to foreign policy was largely responsible for Germany’s re-entry into the community of nations, including the securing of foreign loans and the negotiation of several treaties and agreements.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The leadership of Gustav Stresemann”, Alpha History, 2014, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/gustav-stresemann/.