From 1924 Weimar foreign relations were shaped by the firm but pragmatic guiding hand of Gustav Stresemann. Though Stresemann began his political life as a conservative nationalist, his views aligned with those on the far right, he came to recognise that Germany’s fate was inextricably linked to her place in Europe. If Germany could not restore good relations with her European neighbours, Stresemann contended, the nation would either collapse from within or be pulled apart by external forces. It was essential that Berlin formed an effective working relationship, particularly with France, Germany’s most powerful continental neighbour, and the United States, a potential economic partner and benefactor. To achieve this, foreign governments must be convinced that Germany no longer posed any military threat – or indeed had any appetite for war.

In mid-1925 Stresemann began exchanging diplomatic notes with the foreign ministers of France and Britain. These notes were less bellicose and more conciliatory than previous communications, suggesting the Weimar government might be prepared to form a working relationship with Paris and London. These exchanges culminated in a five-nation diplomatic conference, held in Locarno, Switzerland, in October that year. The negotiations culminated in the Locarno Treaties (December 1925) which established the Franco-German and Belgian-German borders, as well as restoring normal diplomatic relations between Germany and her former enemies. All parties to Locarno agreed to abide by League of Nations rulings, should there be any future border or territorial disputes. Germany accepted that the Rhineland should remain demilitarised.

There was one area where Stresemann did not abandon his nationalism: his attitude towards Poland. Like many of the German right wing, Stresemann had a low regard for Polish sovereignty. He despised the Danzig corridor and Poland’s possession of former German territories granted to it at Versailles. At Locarno, Stresemann refused to offer any guarantees about Germany’s eastern frontiers with Poland and Czechoslovakia. He silently hoped that if Germany’s western borders could be secured, France and Belgium might not oppose moves to recover lost territory from Poland or Czechoslovakia.

“Diplomacy served as a lightning rod for the currents of opposition to the Weimar Republic. The nearly universal agreement on revising or terminating the Versailles settlement was complemented by equally widespread disagreement on the most effective means of attaining that end. Bitter public controversy accompanied every diplomatic undertaking. Foreign policy initiatives of all kinds were sure to provoke storms of outrage. Stresemann, as the chief architect of German foreign policy for the better part of a decade, was acutely conscious of the constrictions imposed upon [him] by this volatility of public opinion.”

David T. Murphy, historian

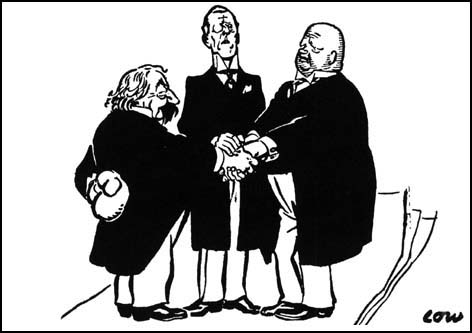

The Locarno treaties seemed to have secured European peace. Britain and Italy countersigned these guarantees and agreed to intervene if Germany’s western frontiers were violated. The treaties filled Europe with a sense of peaceful negotiation and stability – the ‘spirit of Locarno’ – that was a welcome relief following the hostilities of the war and the retribution of Versailles. Locarno also paved the way for Germany’s admission to the League of Nations; full membership was granted in September 1926. It was a triumph for the policy of Stresemann, who for two years had worked tirelessly to restore Germany’s good reputation and status within the international community. The nationalists in Germany, however, viewed Locarno as yet another back down by a government more eager to negotiate than fight for German territory. Many also distrusted the motives of the French negotiator, Briand, who is shown in this British cartoon (see picture) shaking hands with Stresemann while concealing a boxing glove.

Stresemann followed up the Locarno agreements with the Treaty of Berlin, a five-year agreement with the Soviet Union, signed in April 1926. This treaty sought to further restore diplomatic relations and ensure neutrality between Berlin and Moscow. The two countries already had a working agreement in place (the Treaty of Rapallo, signed in 1922) but the Berlin treaty extended and strengthened this arrangement. It also contained non-aggression clauses: Germany and the Soviet Union committed to neutrality if the other was attacked by a hostile power, while each promised not to enter into coalitions or alliances against the other.

The culmination of Stresemann’s conciliatory foreign policy came in August 1928, with Germany’s signing of the Kellogg-Briand Pact. This pact was effectively a multilateral declaration of peace, outlawing the use of war “as an instrument of national policy”. The agreement was hailed around the globe as a breakthrough for peace. A decade after the deadliest war in human history, world leaders seemed to have abolished war for the foreseeable future. Though Stresemann did not initiate this treaty, he nevertheless gave it his full support, both within Germany and abroad. This attitude provided the world with the image of a new Germany, now devoid of belligerent militarism and instead committed to diplomacy and peace.

1. Foreign relations under Weimar were initially troublesome but became more cordial in the 1920s.

2. Failure to pay reparations led to mounting tensions with France and, eventually, the occupation of the Ruhr.

3. Germany received financial assistance from the US, however, through the Dawes Plan and Young Plan.

4. Under Stresemann, Germany participated in the Locarno Pact negotiations, which affirmed several borders.

5. The Kellogg-Briand Pact was signed in 1928 and rejected war, ushering in hopes of a peaceful Europe.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Weimar foreign relations”, Alpha History, 2014, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/weimar-foreign-relations/.