The ‘Battle of the Bogside’ is a name given to violence and rioting that erupted in Derry in August 1969. Many historians consider it the first significant confrontations of the Troubles. The fighting in Bogside erupted at a time when tensions were running high. The emergence of the civil rights movement had exposed injustice, inequality and discrimination against Northern Ireland’s Catholic communities. Loyalists, in contrast, saw the civil rights movement as a front for radical Republicans and a threat to British sovereignty in Northern Ireland. These sectarian tensions needed only a flashpoint to erupt into violence. As has often been the case in Northern Ireland, the flashpoint was a Protestant march. What began with insults and jibes quickly escalated into rock throwing and assaults. Within a few hours, the violence had spread elsewhere and Northern Ireland was ablaze with rioting.

Civil rights and marches

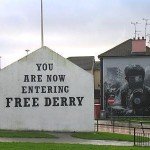

While the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) focused on the advancement of civil rights, many Unionists suspected NICRA of being a front for Catholic and Republican groups. They also rejected Northern Ireland prime minister Terence O’Neill’s political reforms and housing allocation concessions, floated in 1968. NICRA’s decision to conduct marches and protests in late 1968 and early 1969, in defiance of government bans, caused growing unease between Nationalists and Unionists. Catholic groups and communities, already embittered by a strong sense of injustice, resolved to fiercely protect areas they considered to be theirs. Nationalist suspicions increased further when a People’s Democracy awareness march (January 1969) was violently ambushed by Unionists near Burntollet, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) doing little to protect the marchers. If the government and the police were not going to defend Northern Ireland’s Catholics then Catholics, it seemed, would have to defend themselves. One visible sign of the hardening of attitudes towards their areas is the 1969 Lecky Road mural, “You are now entering Free Derry”, a reminder that the area was Nationalist.

In Northern Ireland, marches have a long history of inciting trouble and, occasionally, violence. Marches and parades are an important aspect of the country’s culture: they commemorate significant events in history and celebrate political and religious identity. The majority of marches are conducted by Loyalist and Protestant groups like the Orange Order, the Apprentice Boys of Derry and the Royal Black Institution. During the ‘parading season’, which runs from early June until mid-July, these groups organise and conduct hundreds of parades across the Six Counties. They culminate in marches on July 12th to commemorate the Battle of the Boyne (1690). Though criticised by some as triumphalist and provocative, most Loyalist marches pass without serious incident. Trouble has usually arisen when these marches approach or pass through Catholic strongholds. The annual Orange Order march in Portadown, for example, follows the same route used since 1807, even though this route now traverses Catholic residential areas. The Orange Order’s refusal to change the route of the march – and the Catholic community’s refusal to tolerate it – leads to tension, unrest and conflict almost every July.

The Unionist government intervenes

These marches were a flashpoint for sectarian violence during the Troubles, particularly in the summer of 1969 when tensions were already near boiling point. Nationalists were incensed that the Northern Ireland government, now led by James Chichester-Clark, had banned marches organised by NICRA, People’s Democracy and other civil rights groups. Loyalist parades, however, were allowed to continue, deemed to be “customary” rather than political. On August 12th around 15,000 Apprentice Boys, a Derry-based Protestant group, ignored police warnings and marched through the city. Their route took them dangerously close to the Bogside, a Catholic stronghold. Bogside residents responded by taunting the marchers and the Apprentice Boys responded in kind. As the situation intensified marchers began throwing pennies, a contemptuous gesture intended to mock Catholic poverty. Residents of the Bogside retaliated by using slingshots to fire marbles and before long both sides were also hurling stones. This led to the outbreak of a violent and bloody riot.

As additional RUC units arrived Bogside locals, fearing police baton charges, erected barricades using old furniture, wire and other scavenged materials. One company of RUC officers entered the Bogside and attempted to dismantle a barricade on Rossville Street; what this was intended to achieve is unclear. These officers were followed by a small but hostile group of Loyalists who had broken away from the Apprentice Boys’ march. On entering the Bogside both the RUC and the Loyalists were pelted with stones, projectiles and Molotov cocktails (homemade firebombs) and quickly driven back. Of the 60 or so RUC officers who entered the Bogside 43 were injured, some of them badly burned. The RUC was inadequately equipped to cope with the escalating violence. Its officers had armoured vehicles and water cannons but no authorisation to use them, while there was a lack of adequate riot gear. Many RUC officers ended up fighting hand-to-hand with Catholic rioters. On the evening of August 12th a contingent of ‘B-Specials’, the much-despised Special Constabulary, was deployed in the Bogside. This only infuriated Nationalists further. The RUC bombarded the area with almost 1,100 canisters of tear gas, a response that affected children, the elderly and the infirm more than the rioters themselves.

The violence spreads

“At least some elements of the IRA were prepared to go against the party line from Dublin and move to defend their beleaguered community in the Bogside. Sean Keenan became chairman of the Derry Citizens Defence Association. Keenan’s men knew what needed to be done. Street committees were formed with the defence of the Bogside in mind. Seven of Keenan’s co-founders were members of the James Connolly Republican Club – Sinn Fein by another name. Plans were laid to erect barricades at strategic points; Keenan announced that people were to defend themselves with ‘sticks, stones and the good old petrol bomb’. Firearms were ruled out, at least at this stage.”

Peter Taylor, historian

The sectarian violence in the Bogside soon spread to other parts of Northern Ireland. The worst rioting occurred in Belfast, where Catholics and Loyalists traded blows, missiles and gunfire for several days. NICRA hastily organised demonstrations in central Belfast, to draw police away from Derry. On August 13th around 1,500 Nationalists marched along Springfield Road while a small group, possibly made up of IRA volunteers and youth members, attacked a RUC station with petrol bombs. The following day RUC officers, under fire from snipers, fired a Browning machine-gun into the Divis flats, hitting and killing nine-year-old Patrick Rooney. Riots, destruction and gunfighting also erupted in other parts of Belfast, as well as Dungannon, Dungiven, Coalisland, Newry, Strabane, Armagh and Crossmaglen. In the Republic of Ireland taoiseach Jack Lynch described the situation as dire. Lynch condemned the RUC as partisan and dangerous and called for intervention by the United Nations; he also ordered ambulances to be stationed along the border with Northern Ireland. Lynch’s comments raised the ire of Loyalists, who considered any interference or commentary from the Republic as provocative.

After two days of rioting and violence, Stormont requested military support from London. The British Army was deployed in Northern Ireland on August 14th under Operation Banner. British troops entered Derry on August 14th and Belfast the following day. The British were warmly welcomed at first: Catholics considered their soldiers more neutral than the RUC or the ‘B-Specials’. Many believed the Army’s strong but temporary presence would arrest the violence and protect Catholics from Loyalist persecution. Arriving British soldiers were greeted with cups of tea and hearty cheers from locals. This optimistic outlook continued until Christmas 1969 when some British troops were showered with gifts. This spirit of hope did not last long. While the British Army was non-sectarian and largely apolitical, its mission was to assist the Northern Ireland government in restoring order – not to protect Catholics from the police or the government. In the first months of 1970, the Army participated in anti-rioting operations alongside the RUC. The Falls curfew (July 1970) – a three-day British Army search-and-arrest operation in the Falls district of Belfast, where four civilians were shot dead – marked the end of any honeymoon between Catholic civilians and British soldiers.

1. The Battle of the Bogside refers to several days of violence and rioting. It began in Bogside, a Catholic area of Derry in the city’s west and just outside the city walls.

2. In August 1969 around 12,000 Protestant Apprentice Boys marched dangerously close to Bogside. Taunting between marchers and residents soon escalated into violence and rioting.

3. RUC officers were deployed to suppress the violence. Several RUC officers entered the Bogside to dismantle barricades but were driven back. Later the area was flooded with CS gas.

4. The fighting and violence in Derry quickly spread to several other towns and cities in Northern Ireland. Rioting and violence were particularly severe in Belfast.

5. This unrest stretched the RUC critically thin. The government responded by requesting support from British soldiers. British troops entered Derry on August 14th, marking the beginning of Operation Banner.

BBC News: Police break up NICRA civil rights march in Derry (October 1968)

Irish taoiseach Jack Lynch on the causes of the unrest in Derry (October 1968)

Terence O’Neill: “Ulster stands at the crossroads” (December 1968)

Bernadette Devlin on the Loyalist ambush at Burntollet (January 1969)

Terence O’Neill calls for an end to marches and violence (January 1969)

A joint communique on reforms in Northern Ireland (March 1969)

BBC News: Police use tear gas in Bogside (August 1969)

Irish taoiseach Jack Lynch condemns violence in Northern Ireland (August 1969)

Britain’s Home Secretary promises reforms in Northern Ireland (August 1969)

Cameron Report on causes of disorder in Northern Ireland (September 1969)

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole and J. Llewellyn, “The Battle of the Bogside”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/battle-of-the-bogside/