Who are Catholics and Protestants?

Catholics and Protestants belong to two different branches of the Christian religion. Roman Catholicism is the oldest form of Christianity. The theology and organisation of the Catholic church date back to the Apostles of Jesus Christ and the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD. Since then the Catholic church has been led and guided by the Pope and his office, the Holy See, which is based in the Vatican City in Rome.

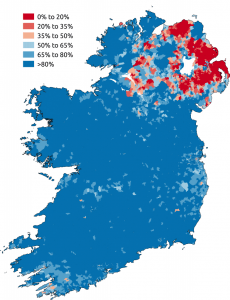

Catholic missionaries introduced their religion to Ireland during the 400s. The most famous of these missionaries was a British-born priest, Patrick, who became the patron saint of Ireland. In 1971 around 80 per cent of people in the Republic of Ireland identified as Catholic. The figure was much lower in Northern Ireland, where almost 32 per cent of the population identified as Catholic.

Protestant religions are much younger. Protestantism emerged in the 16th century as a breakaway movement from Catholicism. This period of separation is known as the Protestant Reformation. The Reformation was instigated by religious leaders like Martin Luther, who questioned the doctrines of the Catholic church and protested against some of its rituals (hence the name ‘Protestants’).

The Reformation gave rise to a number of Protestant churches, including the Anglicans (Church of England), Presbyterians, Lutherans, Baptists, Methodists and Adventists. Protestantism was imported into Ireland, particularly northern Ireland, by English colonists and settlers.

By 1971 approximately 53 per cent of Northern Irelanders belonged to a Protestant religion. The vast majority were members of the Presbyterian Church or the Church of Ireland. In the Republic of Ireland only four per cent of citizens identified as Protestant.

Who are Nationalists and Republicans?

Two groups you will encounter when reading about the Troubles are Nationalists and Republicans. In literal terms, a nationalist is someone who demands political independence and sovereignty for their country, while a republican supports government without monarchy or hereditary rulers.

In the context of Northern Ireland, the labels Nationalist and Republican are often assumed to mean the same thing: any group or person who believes in a unified Ireland, free of British control.

This is a generalisation, however. There may be subtle differences between a Nationalist and a Republican, and some Northern Irelanders may identify as one but not the other. Some historians and commentators claim that Nationalists seek Irish reunification through negotiation and peaceful methods, while Republicans are more radical and may advocate violence.

Most Nationalists and Republicans are Catholic, though the socialists among them are atheists and a smaller number belong to Protestantism or another faith.

Who are Unionists and Loyalists?

At the opposite end of the spectrum are Unionists and Loyalists. As with Nationalists and Republicans, many use these terms interchangeably – but there are some subtle but important differences.

The Unionist position is chiefly political: Unionists support the existence of Northern Ireland, its ongoing union with Great Britain and its right to self-government.

Loyalists hold a firmer position. Ulster Loyalism draws heavily on British nationalism, history, tradition and culture. Loyalists venerate the British monarchy and emphasise their historical and cultural ties with Britain. They utilise and cherish British motifs like the Union Jack, the St George’s Cross, the St Andrew’s Cross and symbols of monarchy.

Ulster Loyalists are usually more strident and intense than Unionists; some have described them as being ‘more British than Britons’. Loyalism is associated with paramilitary groups while Unionism tends to reside in political parties. Most Unionists and almost all Loyalists are Protestants.

What is sectarianism?

Sectarianism refers to stark and dangerous divisions within a society or community. Sectarian divisions can be based on political differences, class, religion, ethnicity or tribal identity. As these divisions evolve and widen they may lead to bigotry and prejudice, discrimination, tension and conflict.

Religious sectarianism between Catholics and Protestants has shaped and disrupted Ireland for centuries. It dates back to the anti-Catholic Penal Laws, passed by English rulers in the late 1600s.

Despite this painful history, the sectarian violence of the Troubles was not entirely religious. The civil rights movement of the 1960s exposed the extent to which Northern Ireland’s Catholic population had been marginalised, disenfranchised and suffered discrimination in jobs, education and housing. These revelations fuelled a more potent sectarianism that combined political, economic, religious and cultural differences.

What is Ulster?

Ulster is a name for the northern regions of Ireland. Ulster has both historical and modern interpretations. Traditionally, the name Ulster referred to nine counties in the north of Ireland: Antrim, Armagh, Cavan, Donegal, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry, Monaghan and Tyrone.

When Ireland was partitioned in 1920, six of these counties (Antrim, Amargh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone) were combined to form Northern Ireland. From this point the name Ulster assumed different meanings for Nationalists and Loyalists.

When Nationalists say “Ulster” it is usually in its traditional context, a reference to the nine northern counties that once belonged to Ireland. When Loyalists use the word “Ulster” they refer to the six counties of Northern Ireland under British sovereignty. These disputes over the meaning of a single word are symbolic of the historical divisions in Northern Ireland.

What are paramilitary groups?

A paramilitary group is an organisation that resembles a military force. Most paramilitary groups have a strategic mission, employ a command structure and use military-style training and tactics. They assemble caches of weapons, engage in espionage and produce propaganda.

Unlike military forces, however, paramilitary groups are not organised or sanctioned by the state. These groups have no formal connections with the government and often operate outside the law. For this reason paramilitary volunteers usually conceal their identity, wearing balaclavas or similar.

Several paramilitary groups were active in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. These groups are categorised as either Republican or Loyalist. Republican paramilitary groups included the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and its various splinter groups – the Provisional IRA, the Official IRA, the Continuity IRA, the Real IRA and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). The main Loyalist paramilitary groups were the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF). These groups were responsible for the vast majority of deaths and injuries inflicted during the Troubles.

Visit our glossary pages A-K and L-Z for definitions of more specific topics related to the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

© Alpha History 2021. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole, Jennifer Llewellyn and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole et al, “Northern Ireland glossary”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/northern-ireland-glossary/