The Weimar Reichstag (the German parliament or assembly) was notorious for its division, instability and ineffectiveness. Historians often cite these conditions as a contributing factor to rising extremism in Weimar Germany. Under Bismarck and Kaiser Wilhelm II, Germans had grown accustomed to a strong, stable and decisive government. But the Weimar political system was fundamentally democratic, designed to allow a multiplicity of voices and points-of-view. This arrangement may have worked if there had been a national consensus about Germany’s political and economic future. But the Weimar period was one of extreme political divisions – and the troubled Weimar Reichstag reflected and exacerbated these divisions, rather than serving to close them.

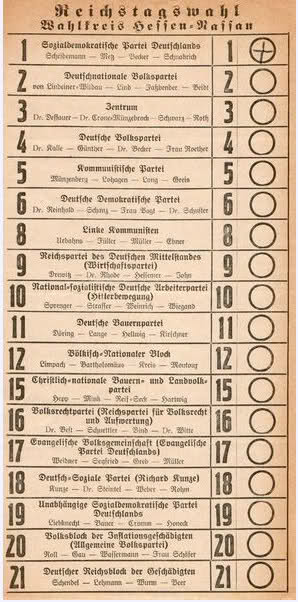

A significant problem in the Reichstag was its plethora of divergent political parties. The electoral law adopted in April 1920 implemented a proportional system of voting. Parties were awarded Reichstag seats not by winning an absolute majority but by meeting a quota, based on the proportion of votes cast. This system encouraged the participation of a wide variety of parties, including fringe or regional groups. It was quite common for ballot papers to contain more than 30 parties and candidates (the ballot paper on this page, from the 1928 election, contains 21.) But the system not only encouraged smaller parties to participate, it made it easier for them to win seats. In most Reichstag elections around 60,000 votes, sometimes less, was enough to win a seat. In 1920 the tiny Bavarian Farmers’ League party won just over 200,000 votes – almost all from Bavaria – yet this was enough to net it four seats in the national Reichstag.

As a consequence, the Reichstag was clogged with more than a dozen different parties from across the political spectrum. In the 1920 election, 11 different parties won Reichstag seats. By 1930, there were 14 different parties represented on the floor of the Reichstag. Proportional voting and the abundance of parties made it impossible for one or even two parties to ‘dominate’ the Reichstag. No party ever held a majority of seats in its own right; the closest any party came was the NSDAP in July 1932 when it won 37 per cent of seats. This political disunity in the Reichstag required the chancellor and his cabinet to organise coalitions (voting blocs containing different parties) in order to get legislation passed.

The lack of majority government in the Reichstag made executive government difficult and, at times, almost impossible. The nominal head of government was the chancellor, who led a cabinet of ministers. All were appointed by the president, who in most cases selected a cabinet he believed could steer laws through the Reichstag. Passing legislation was necessary to govern effectively – but in the Weimar Reichstag it was difficult at the best of times, and impossible at the worst. Coalitions were continually being formed and consolidated, tested by legislation, undermined by different views, fragmented, patched up and dissolved – only for the process to begin again. Parties found it difficult to set aside their ideological differences for any length of time. The Reichstag was often paralysed by division and unable or unwilling to pass legislation.

Richard Thoma, writer

These difficulties meant that most Weimar chancellors found it impossible to get much done. When it seemed that a chancellor could no longer work with the Reichstag to pass legislation, there were two options: the chancellor could ask the president to pass emergency decrees, or the president could replace him. Between 1919 and 1933 the German chancellor was replaced fifteen times, each change also requiring a new cabinet of ministers. The Reichstag itself was hardly more stable: there were nine general elections held during the same fourteen-year period.

The period after 1924, with its less frequent changes of government and improved economic conditions, is often described as the ‘Golden Age of Weimar’. To the outsider, it seemed a brief period of stabilisation. Political violence and extremist rhetoric eased; domestic government functioned better than it had done in the early 1920s; Stresemann led reforms in foreign policy and international relations. But these outcomes disguised a lack of fundamental stability and cohesion, particularly within the Reichstag. Forming and maintaining coalition governments continued to be enormously difficult. The lack of trust between the SPD and centrist and right-wing parties remained the most significant obstacle to enduring coalitions.

1. The Weimar government is known for political instability and frequent changes of chancellor and ministers.

2. This is in part due to the voting system, that encouraged the presence of many parties in the Reichstag.

3. With no party ever winning an absolute majority, government was formed by coalitions of several parties.

4. Chancellors were chosen based on their ability to steer laws through the Reichstag, a most difficult task.

5. Changes in government eased after 1924, though the appearance of greater stability was superficial.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Weimar Reichstag”, Alpha History, 2014, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/weimar-reichstag/.