The fate of the Weimar Republic was shaped to a large extent by the Treaty of Versailles. Drafted in Paris in the opening months of 1919, the treaty was one of several multi-national agreements that formally ended World War I. The Paris peace conferences had a wide and complex array of tasks to perform. They examined pre-war territorial disputes and attempted to resolve them by re-drawing Europe’s borders. They considered and evaluated movements for independence and self-determination, establishing several new sovereign nations. They finalised the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire (Treaty of Saint-Germain) the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire (Treaty of Sevres) and the composition of eastern Europe (Treaty of Neuilly). But the most pressing issue in Paris was what should be done with Germany.

One long-standing peace proposal was United States president Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Point plan. Wilson’s Fourteen Points had been on the table for almost a year, having been unveiled in a speech in January 1918. Wilson’s plan called for a reduction in armaments in all nations, the lifting of economic barriers, an end to secretive and disruptive alliances and freedom on the high seas. It also proposed international negotiation and dispute resolution, to be facilitated by a newly formed League of Nations. The Fourteen Points contained no specific punitive measures against Germany, other than the return of captured French and Belgian territory. For this reason, it became popular with the anti-war movement within Germany in the final months of the war; in 1918 it was cited and praised both in the Reichstagand by the Kiel mutineers. The German government’s final decision to surrender was largely motivated by its belief that Wilson’s Fourteen Points would form the basis of a post-war treaty.

Wilson’s plan, however, was not widely supported in France or Britain, where attitudes towards Germany were much less conciliatory. The prevailing attitude in Paris and London was that Germany had been chiefly, if not entirely responsible for the outbreak of the war. For that, many argued, Germany should be held accountable and punished. They also called for measures to reduce Germany’s ability to make war in the future, by dismantling or reducing her military and industrial sectors. The push to castrate Germany’s military capacity came chiefly from the French, who had the most to fear from its eastern neighbour. At the Paris negotiations, French prime minister Georges Clemenceau argued forcefully for punitive and restrictive measures against Germany. Clemenceau wanted to send Germany’s economy backwards, from a first-world industrial nation into a weak cluster of provinces concerned with agricultural production and small-scale manufacturing.

The Treaty of Versailles came to reflect much more of Clemenceau’s punitive approach than Wilson’s conciliatory one. Among its main terms and conditions:

- Germany lost substantial amounts of territory. She was stripped of all overseas colonies and forced to surrender large amounts of European territory, including some of significant strategic or industrial value. Alsace and Lorraine were returned to France, while other areas were surrendered to Belgium, Lithuania, Czechoslovakia and Poland.

- The Rhineland, an area of German territory bordering France, was ordered to be demilitarised, as a means of protecting the French border. Another German border region, the Saarland, was occupied and administered by France.

- Germany was banned from entering into any political union or confederation with Austria.

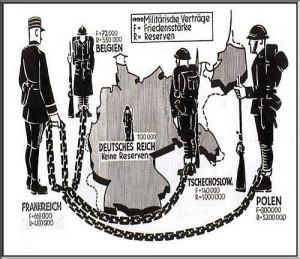

- The German Reichswehr (army) was restricted in size. It could contain no more than 100,000 men and was forbidden from using conscription to fill its ranks. There were also restrictions on the size and composition of its officer class.

- The German military was subject to other restrictions and prohibitions. Naval vessels were restricted in tonnage while bans were imposed on the production or acquisition of tanks, heavy artillery, chemical weapons, aircraft, airships and submarines.

- The treaty’s Article 231 (the ‘war guilt clause’) determined that Germany was single-handedly responsible for initiating the war, thus providing a legal basis for the payment of war reparations to the Allies.

These terms were formulated by the Allies without the input of Germany, which was not permitted to attend the Paris peace summit. In May 1919 German delegates were finally invited to Paris. After being kept waiting for several days, they were presented with the draft treaty. The German foreign minister, Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau, spoke at Versailles, suggesting that while his country was prepared to make amends for its wartime excesses, the suggestion that Germany was alone in starting the war or exceeding the rules of war was baseless:

We are ready to admit that unjust things have been done. We have not come here to diminish the responsibility of the men who have waged war politically and economically, or to deny that breaches of the law of nations have been committed… But the measure of guilt of all those who have taken part can be established only by an impartial inquiry, a neutral commission before which all the principals in the tragedy can be allowed to speak, and to which all archives are open. We have asked for such an inquiry and we ask for it once more… In their hearts, the German people will resign themselves to a hard lot if the bases of peace are mutually agreed on and not destroyed. A peace which cannot be defended before the world as a peace of justice will always invite new resistance. No one could sign it with a clear conscience, for it could not be carried out. No one could venture to guarantee its execution, though this obligation is required by the signing of the treaty.

When news of the treaty reached Germany it generated a firestorm of public anger. Germans had expected a fair and even-handed agreement based on Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Instead, they were handed what they called the “Versailles diktat” – a treaty that was not negotiated between equals but was forced on a war-ravaged and starving people at the point of a gun. There were few moments of national unity in Weimar Germany – but the response to Versailles was one of them. Erich Ludendorff considered the treaty the work of Jews, bankers and plotting socialists. Gustav Stresemann described it as a “moral, political and economic death sentence”. “We will be destroyed,” said Walter Rathenau. In the Weimar Reichstag, delegates from all political parties except the USPD rose to condemn the Versailles treaty and the conduct of the Allies. Almost every newspaper in Germany slammed the treaty and screamed for the government to reject it.

For two tense months, the Weimar government debated the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles. The issue brought about the demise of Weimar’s first chancellor, Philipp Scheidemann, who resigned rather than ratify the treaty, which he deemed a “murderous plan”. President Friedrich Ebert was also opposed to the Versailles treaty. In June he contacted military commanders and asked whether the army could defend the nation if the government refused to sign the treaty and the Allies resumed the war. Both Paul von Hindenburg and Wilhelm Groener advised the Reichstag that the army lacked material and munitions and could not withstand an Allied offensive or invasion of Germany. Any refusal to comply with Versailles would also prolong the Allied food blockade, which was still ongoing in June 1919 and contributing to thousands of civilian deaths from starvation. Confronted with this advice, the Reichstag had no alternative but to submit to the Allies. Germany’s delegates signed the treaty on June 28th 1919. It was ratified by the Weimar assembly almost a fortnight later (July 9th), passed 209 votes to 116.

For the SPD and other moderates, the acceptance of Versailles was a necessary measure, given reluctantly to prevent more war and bloodshed, an Allied invasion of Germany and the possible dissolution of the German state. Some accepted Versailles in the hope that it could be renegotiated and relaxed later. Those in the military and the far right, however, saw it as yet another betrayal. “Today German honour is dragged to the grave. Never forget it!” screamed one nationalist newspaper. “The German people will advance again to regain their pride. We will have our revenge for the shame of 1919!” Conspiracists on the far right claimed the ratification was more evidence of destructive forces at work in Germany’s civilian government. The Treaty of Versailles – or rather the question of how Germany should have responded to it – would contribute to political divisions for the life of the Weimar Republic.

1. The Treaty of Versailles, drafted in 1919, formally concluded hostilities between the Allies and Germany.

2. Germany was not a party to treaty negotiations but was handed peace terms in May 1919, inviting protest.

3. The treaty was widely opposed within Germany, the government briefly considered refusing to sign and ratify.

4. Faced with a resumption of the war and an Allied invasion, the Weimar government reluctantly ordered the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and organised its ratification by the Reichstag.

5. This acceptance of the treaty outraged nationalist groups, who considered it another example of the Dolchstosselegende. Versailles and its harsh terms contributed to more than a decade of political division in the Weimar Republic.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “What impact did the Treaty of Versailles have on the Republic?”, Alpha History, 2018, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/treaty-of-versailles/.