The Allies’ determination to extract reparations from Germany hindered the nation’s recovery after World War I. Vast sums of money were demanded from Berlin, compensation for the Kaiserreich’s role in instigating war. Germany’s negotiators at the Paris peace conference gave an in-principle agreement to the payment of reparations. The legal basis for reparations was provided by Article 231 of the Versailles treaty, the infamous ‘war guilt’ clause that deemed Germany responsible for “all the loss and damage” suffered by Allied nations during the war. But the Paris negotiators were unwilling to fix a final reparations figure or determine how reparations should be recovered. This task was instead left to an Inter-Allied Reparations Commission, formed in 1919 by the governments of Britain, France, Belgium, Italy and Japan.

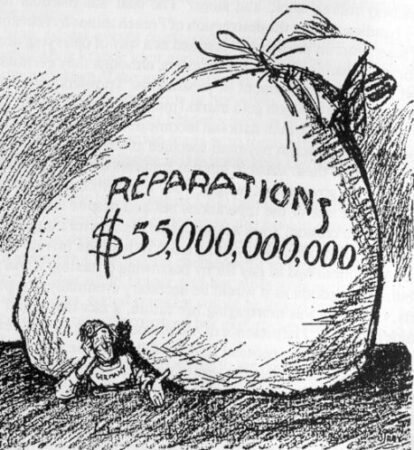

The commission met over 1920 and again in Paris in January 1921, where it proposed a final figure of 269 billion gold marks, or £UK11.3 billion. This was an astonishing amount by any measure. It was the equivalent of 96,000 tons of gold – or around half the known gold reserves of the entire world; today it would equate to almost $US500,000,000,000 (half a trillion American dollars). The German delegates refused to accept this figure, quite understandably, forcing the commission to reconvene in London in March. By then, Germany was under considerable pressure to agree to a final reparations figure. Berlin had failed to pay a £1 billion interim instalment, leading to the occupation of three industrial cities along the Rhine.

In April the London meeting of the Commission fixed a final reparations figure of £6.6 billion. The reparations instalments were to be paid quarterly in gold or foreign exchange backed by gold, along with tradable commodities such as steel, raw iron or coal. Berlin was informed that any defaults on these payments would lead to the occupation of the industrial Ruhr region and the confiscation of raw materials and industrial equipment there. Though this revised amount was less than two-thirds the figure first proposed, it remained well beyond the capacity of the war-ravaged German economy. The reparations figure generated international debate for a decade. In England, the noted economist John Maynard Keynes criticised the agreed figure, suggesting that the true amount of war damages had been exaggerated by the Allies, particularly France and Belgium. Forcing Germany to pay the full amount, Keynes argued, would not only devastate the German economy, it would have a detrimental impact on European trade and probably generate considerable political instability.

Stephen Lee, historian

Germany made an initial reparations payment of $250 million – or about 0.8 percent of the total – in August 1921. But even this placed enormous strains on the German economy, which had dwindling gold reserves, little foreign trade and was reliant on imported raw materials for its industries. In late 1921 the Weimar government asked the Reparations Commission for a moratorium on payments. This was granted in May 1922, despite the opposition of the French government. In 1922 the value of the German Reichsmark collapsed; by late in the year it took almost 3,500 Reichsmarks to purchase one US dollar. Unable to import or buy foreign exchange, the German government found itself unable to meet its reparations obligations. The French government, believing the German government was acting purposefully and dishonestly by withholding payments, began to agitate for punitive action.

Germany was not the only European nation struggling to pay its wartime debts. France was itself defaulting on instalments for its war debts, particularly those to its largest creditor, the United States. A German cartoon of the early 1920s showed the French prime minister threatening war against Germany but being obstructed by ‘Uncle Sam’, who suggested: “Why don’t you pay for your last war before starting another”. The post-war economic malaise and the issues of war debts and reparations remained divisive issues for much of the 1920s. The reparations figures were constantly being challenged and revised, most notably by the Dawes Plan (1924) and the Young Plan (1929).

1. The defeated Germany agreed to pay war reparations, as determined at the Versailles conference.

2. The French were the strongest advocates for a massive figure, hoping to keep Germany bankrupt and weak.

3. The final figure proved too much for Germany’s struggling economy to pay, though she met her first instalment.

4. The German economy slumped in 1922, with currency inflation, strikes and falling production.

5. Unable to make further payments, the Germans saw French troops occupy the Ruhr industrial region.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “War reparations and Weimar Germany”, Alpha History, 2018, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/reparations/.