The First Indochina War (December 1946 to August 1954) saw the Viet Minh and French colonial forces battle for control of Vietnam. In the West this conflict is called the First Indochina War; in Vietnam it is referred to as the Anti-French War. It unfolded after the Japanese surrender in August 1945, which left Vietnam without a single national government. Ho Chi Minh seized the opportunity to declare Vietnamese independence on September 2nd 1945 – but the arrival of Chinese and British troops, tasked with overseeing the Japanese withdrawal, undermined the Viet Minh and its grip on power. Driven by anti-communist agendas, the Chinese and British allowed the restoration of French colonial rule, rather than leaving Vietnam in the hands of “red bandits”. By late 1946 the French had mobilised 50,000 troops in Vietnam and regained control of Saigon. In November, French naval vessels bombarded the northern port city of Haiphong, killing large numbers of civilians. The Viet Minh retaliated by attacking French positions in Haiphong and Hanoi, though these attacks were repelled by French artillery and naval guns. By mid-December, the two sides were openly at war.

Aside from Ho Chi Minh, the Viet Minh’s most notable military leader was Vo Nguyen Giap. The beneficiary of a French education, Giap graduated from the University of Hanoi, where he had studied history and politics. A learned and articulate man, Giap spent most of the 1930s teaching history, while contributing to and editing several socialist newspapers. In 1939 Giap was forced to flee Vietnam because of his anti-French political activities. He remained in exile for five years, during which French authorities arrested and executed most of his family. While in exile in China, Giap joined up with Ho Chi Minh and other Viet Minh rebels. After their 1944 return to Vietnam, Giap was tasked with overseeing the Viet Minh’s military forces. His leadership had a profound effect on the outcomes of the First Indochina War and, later, the Vietnam War.

During the First Indochina War, the Viet Minh encountered similar difficulties experienced by other anti-colonial forces. Despite heavily outnumbering French forces the Viet Minh were hindered by severe weapons shortages, particularly a lack of artillery and munitions. Most Viet Minh weapons had been retrieved from the retreating Japanese or seized from captured French. By the end of 1946, Giap’s northern Viet Minh units boasted 60,000 men – but they were armed with only 40,000 rifles. In addition, Viet Minh soldiers were largely untrained and had little understanding of military organisation, discipline or strategy. Giap was not daunted by these shortcomings. A keen student of war and revolution, Giap studied the philosophy and tactics of famous leaders, from Sun Tzu to Napoleon, from George Washington to Leon Trotsky. Giap recognised the need for strategies that made use of Viet Minh strengths and exploited French weaknesses. One invaluable source of ideas was a 1936 pamphlet called Problems of Strategy in China’s Revolutionary War, written by Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong. Though Mao was writing of the situation in his own country, his pamphlet had lessons for Giap and the Viet Minh:

“The principal characteristics of China’s revolutionary war are: a vast semi-colonial country which is unevenly developed politically and economically… a big and powerful enemy… and a small and weak [revolutionary] army… These characteristics determine the line for guiding China’s revolutionary war as well as many of its strategic and tactical principles. It is clear that we must [recognise] the guerrilla character of our operations; oppose protracted campaigns and a strategy of quick decision… and instead uphold a strategy of protracted war and campaigns of quick decision; oppose fixed battle lines and positional warfare, and favour fluid battle lines and mobile warfare; oppose fighting merely to rout the enemy, and uphold fighting to annihilate the enemy; oppose the strategy of striking with two fists in two directions at the same time, and uphold the strategy of striking with one fist in one direction at one time.”

Giap and Ho Chi Minh adapted Mao’s strategies to the situation in their own country. It was impossible for the Viet Minh to win large-scale battles against the French; they could not withstand French artillery or match French air support or supply lines. Instead, the Viet Minh sought to avoid decisive battles and withdraw to the countryside, jungles and mountains. There they established bases in areas too remote for the French to attack. In these bases, they planned to train and prepare Viet Minh soldiers for future campaigns. Meanwhile, Viet Minh cadres would move among the peasants, working to build up political support. The backing of the Vietnamese people was important because they could supply food, information and cover for Viet Minh troops (Giap often cited Mao Zedong’s saying: “A guerrilla soldier swims through the people like a fish swims through the sea”). When ready, Viet Minh soldiers would be deployed to launch surprise attacks, ambushes and raids on weaker French positions (while avoiding full-scale battles). Their aim was to prolong the war while inflicting casualties on French soldiers and damage to French resources. The intention was to make the war costly and unpopular back in France. Eventually, French forces would be weakened enough for the Viet Minh to engage them in a decisive battle.

“It is the fight between tiger and elephant. If the tiger stands his ground to fight, the elephant will crush him with its weight. But if he stays agile and keeps his mobility, he will finally vanquish the elephant, who will bleed to death from a multitude of small cuts.”

Ho Chi Minh

French military units that participated in the First Indochina War were called the Corps Expeditionnaire Francais en Extreme-Orient (the ‘French Far-East Expeditionary Corps’, or CEFEO). It was a composite military force containing native Frenchmen, pro-French Vietnamese and troops from other French colonies in Africa, as well as units of the French Foreign Legion. At its peak, the CEFEO numbered more than 200,000 men, the majority Vietnamese. While the CEFEO was better armed and equipped than the Viet Minh, it still suffered from severe shortages. France was economically devastated by World War II so the French government had to mobilise the CEFEO on a shoestring budget. During the first phase of the war, many CEFEO troops had no uniforms or standard-issue weapons; they had to rely on whatever they could scrounge or capture. The situation did not improve until 1953 when the United States began supplying the CEFEO with military aid.

The first two years of the war (1947-48) was marked by sporadic fighting. The CEFEO was able to quickly capture and control the major cities, while the Viet Minh followed Giap’s strategic plan and withdrew into the mountains. In late 1947 the CEFEO launched Operation Lea, an attempt to destroy the Viet Minh leadership base at Bac Can, north of Hanoi. More than 1,000 French paratroopers were dropped into the area, with orders to flush out the Viet Minh hierarchy. Meanwhile, a 15,000-strong CEFEO force was positioned to outflank the retreating Viet Minh and rout them in battle. Despite heavy Viet Minh losses (around 9,000 men) most of their soldiers proved too elusive. “The enemy,” according to one French soldier, “melted into the jungle”.

In early 1949 the French, frustrated by a lack of progress in the war, changed tack. Paris began looking for a political solution rather than a military victory. Hoping to undermine the Viet Minh’s supporter base, France set up an alternative Vietnamese government, more moderate and pro-French than the Viet Minh. Paris began negotiating with figurehead emperor Bao Dai about forming a government. The new regime was to remain part of the French Union but would be self-governing – at least in theory. Bao Dai agreed to the plan and the national capital was moved from Hue to Saigon. This was itself a tactical move because Viet Minh support was much weaker in the south, which contained higher numbers of Vietnamese middle class, Francophiles, Catholics, Confucians, Buddhists, political liberals and moderates. While these groups welcomed Vietnamese independence, they harboured fears about communism and refused to support the Viet Minh, viewing them as lower class bandits led by political troublemakers.

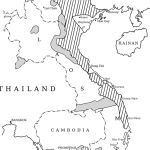

Bao Dai’s new government was encouraged to form a new military force, the Vietnamese National Army (VNA). This was done by recruiting new soldiers but also by co-opting the ‘private’ armies run by cultists, warlords and gangsters. VNA officers were given the same command training as French soldiers. Recruits were promised good pay and the opportunity to serve in France (promises that were later broken). By 1952 the VNA had more than 120,000 soldiers and was fighting alongside the CEFEO in many anti-Viet Minh campaigns. The year 1952 also saw some of the most bitter fighting of the war, as the Viet Minh launched a series of advances in the north, to restore their supply lines and expel the French. When these attacks were unsuccessful, Ho Chi Minh and Giap decided to move men and supplies into Laos – Vietnam’s western neighbour and another French colony – to further stretch CEFEO resources. This shift would facilitate the final decisive engagement of the First Indochina War: the Battle of Dien Bien Phu.

1. Tension and hostility between the independence-seeking Viet Minh and returning French colonial forces led to the outbreak of the First Indochina War in late 1946.

2. The Viet Minh had superior numbers but lack the weapons, munitions and technology of the French. Led by General Giap, they retreated to remote areas to train, gather support and instigate a protracted war.

3. The continuation of the war and some failed military operations led to France seeking a political solution. Paris sought to undermine the Viet Minh by establishing an independent republic of Vietnam.

4. The figurehead emperor Bao Dai was put in charge of this nominally independent state. He was encouraged to form a national army, which later provided support to the French CEFEO.

5. In 1952-53 the Viet Minh began to move men and supplies into remote areas of French-occupied Laos. This change in tactics led to a decisive military confrontation at Dien Bien Phu.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The First Indochina War”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/first-indochina-war/.