Dien Bien Phu was the decisive battle of the First Indochina War. By mid-1953 the conflict was in its seventh year, with no obvious prospect of victory for either side. French generals had tried a variety of tactics to eradicate the Viet Minh, to no avail. Exhausted and devoid of ideas, the CEFEO had no long term vision or military objectives; its officers simply defended their positions and reacted to Viet Minh attacks when they occurred. In France itself, the war had become very unpopular. The French war effort was being propped up by American aid. By the start of 1954, the war had cost $US3 billion, of which the United States had contributed more than a third. France’s unstable domestic politics also undermined the war effort. During the seven years of war, there were 16 changes of government and 13 changes of prime minister – but none offered any satisfactory strategy or long term objectives for Indochina, or took any responsibility for the military failures there. The government’s handling of the war copped stinging criticism in the French press and from left wing politicians. There was also a string of scandals involving military incompetence, corruption, currency deals and arms trading. The Indochina conflict became widely known in France as la sale guerre, or ‘the dirty war’.

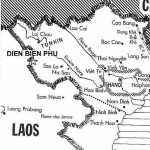

By 1953 Paris was desperately seeking an honourable solution to what now seemed an unwinnable war. Unable to corner or destroy the Viet Minh, French commanders planned a series of fortified positions across Tonkin (northern Vietnam). The CEFEO could not hope to compete with the Viet Minh in the jungles or the mountains – but a string of bases could be heavily defended and used as staging points for mobile operations. French strategists did not think the Viet Minh or its leaders would risk attacking bases protected by high terrain, artillery and air cover. Even if they did, it would play into French hands. The CEFEO also hoped to prevent the transit of enemy forces between Vietnam and Laos, where the Viet Minh was resting and resupplying. To halt this flow, French commanders decided to garrison and fortify an old Japanese airstrip at Dien Bien Phu, 10 kilometres from the Laotian border and 300 kilometres west of Hanoi. In November 1953 almost 2,000 French paratroopers were dropped into the area. They set to work extending and improving the airstrip, to allow more men and supplies to be flown in. Within a few weeks, Dien Bien Phu had been transformed into a major military base.

The Dien Bien Phu base covered five square kilometres and contained nine separate camps. According to legend, French commander Colonel Christian de Castries named the camps after his nine mistresses. It also contained a makeshift brothel, which flew in prostitutes from Hanoi to service 15,000 French troops stationed there. Dien Bien Phu’s location offered tactical advantages and disadvantages. The base sat on the floor of a large valley, surrounded by steep mountains and cliffs, some up to a mile high. Apart from one narrow track leading to the local village, there were no roads or paths into the base. Any enemy offensive against Dien Bien Phu would require a long and arduous trek through the mountainous jungle. The high mountains and inaccessible forest around the base seemed to negate any chance of an artillery assault. French officers thought the location and surrounding terrain made Dien Bien Phu unassailable. But Dien Bien Phu’s isolation, while a defensive advantage, meant it could only be resupplied and reinforced from the air. The region was also subject to low lying cloud and dense monsoonal rainfall, which hampered visibility and flights in and out of the base.

Viet Minh leaders were well aware of the French build up at Dien Bien Phu. They were also aware of the difficulties of mounting an attack in that area. General Vo Nguyen Giap, the Viet Minh’s military chief, understood the strategic importance of Dien Bien Phu – but he was also aware that the French garrison was vulnerable, hundreds of kilometres from Hanoi and surrounded by elevated positions. If an attack could be launched from the mountains around the base, the French could be besieged and starved to surrender. But it would take a monumental effort for the Viet Minh to even reach the mountaintops around Dien Bien Phu, let alone position heavy artillery there. By the start of 1954, Giap had organised around 50,000 Viet Minh troops, almost one-third of his entire army, and marched them to the hilltops around Dien Bien Phu. They were supported by thousands of local peasants, including many women, who provided labour, building roads, clearing jungle and hauling equipment. Among the cargo were several dozen heavy artillery guns, obtained by Giap from the Chinese, as well as Soviet-supplied trucks and tons of small arms, munitions and supplies. All were hauled up steep mountain gradients by hand. Artillery pieces were pulled apart at the foot of mountains and reassembled at the top.

“The huge importance of Dien Bien Phu for France and its army was almost incalculable… the great significance of [these] events was the way in which, imperceptibly at first and then with increasing inevitability, Vietnam changed from a French colonial battle-field to one on which the United States chose to make its stand against what General Matthew B. Ridgway called the ‘dead existence of a godless world’.”

David J. A. Stone, historian

By March 1954, Giap felt secure enough to launch his main offensive. On March 13th his artillery began pounding ‘Camp Beatrice’ in the base’s northern quadrant. Within 12 hours the camp was destroyed, more than 400 French soldiers were dead and the airstrip was unusable. Under cover of darkness, Giap’s men moved from the mountains down into the valley. For 20 days the French and CEFEO forces withstood ferocious attacks from the Viet Minh, with both sides incurring heavy losses. Giap ordered trenches to be dug at strategic points around the valley and the French followed suit. Days of heavy rain flooded the valley floor and filled trenches with mud and water; the battlefield at Dien Bien Phu began to resemble something from the Somme or Passchendaele. With planes unable to land because of the weather and ongoing battle, the French had to be supplied with parachute drops – but the low cloud and poor visibility saw many fall into the hands of the Viet Minh. By mid-April, the Viet Minh had lost around 10,000 men, the French and CEFEO about half that number.

The rest of the world, deep in the grip of the Cold War, watched this struggle between a European power and an Asian communist insurgency. There were repeated calls for military intervention from the United States, in order to save the French at Dien Bien Phu. For a time this was strongly considered in Washington. American military commanders quickly devised a strategy to save the French base. Codenamed ‘Operation Vulture’, it involved intensive low-level bombing runs over the valley and even, if necessary, the use of tactical nuclear weapons against Viet Minh strongholds. President Eisenhower, however, refuse to approve this operation without the support and participation of the British. When London refused, the operation was shelved.

By early May the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu was perilously short of men, munitions, food and medical supplies. On May 7th – the day before the Geneva Conference opened in Switzerland – Giap ordered one final assault. More than 20,000 Viet Minh soldiers swarmed against positions held by around 3,000 able-bodied French troops. By nightfall, they had been overrun, prompting French officers to formally surrender. Giap found himself with more than 11,000 prisoners, including 7,000 Frenchmen; more than a third of them were injured or seriously ill. These prisoners were forced to march more than 300 kilometres to Viet Minh bases in the north-east. Fatigued, brutalised and malnourished along the way, only half reached their destination alive. Of the 11,000 French soldiers stationed at Dien Bien Phu at the start of 1954, fewer than 3,500 would survive.

1. By 1953 the war in Vietnam was going poorly for France, costing both lives and money. Paris began seeking some form of political solution that would allow an honourable withdrawal.

2. In 1953 the French began fortifying an old Japanese airstrip, around 10 kilometres from the Laos border, an attempt to restrict the movement and supply of Viet Minh soldiers.

3. The French considered the base at Dien Bien Phu to be easily defendable. It was isolated, sounded by high mountains and seemingly impregnable to artillery.

4. Viet Minh military chief Vo Nguyen Giap orchestrated an attack on Dien Bien Phu. His forces cleared jungle and hauled artillery up mountains then laid siege to the base in March 1954.

5. After almost two months of battle and siege, the French base at Dien Bien Phu was overrun and some 11,000 CEFEO soldiers were captured. The Viet Minh had won the largest battle of the First Indochina War.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Dien Bien Phu”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/dien-bien-phu/.