The fate of tsarist Russia and its ruling family was bound up in the tragedy of World War I. Russia was drawn into the war by the same follies and errors of judgement that affected the other great powers of Europe: imperial rivalry, poisonous nationalism, military overconfidence, too much trust in alliances and not enough in diplomacy. But while Russia entered the war for similar reasons to her European neighbours, she did not do so on an equal footing. Russia’s economy was still developing and reliant on foreign investment; her industrial sector was incapable of competing with the powerhouse German economy. Three years of total war would exhaust the Russian economy and leave its people starving, freezing and miserable. From this soil, the February Revolution would spring.

Nicholas thought it highly unlikely that the Kaiser would declare war on the kingdom of his own relative. What the tsar did not count on was Wilhelm’s own duplicity, nor did he appreciate the forces of war that had been building in Europe for more than ten years. The alliance system demanded that nations support their allies if one was attacked. This placed the tsar in a perilous position between the Balkan nation of Serbia – a nation with close political, ethnic and religious ties to Russia – and Austria-Hungary and Germany.

When the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was shot dead in Sarajevo in June 1914, it triggered a wave of threats, ultimatums and troop mobilisations. By August, Serbia had been invaded by Austria-Hungary and Russia had declared war in response, prompting the German Kaiser to declare war on his Russian cousin.

As well as the growing international crisis, Nicholas II also had pressing domestic concerns. Anti-government sentiment and unrest had been building since 1912 when tsarist troops butchered hundreds of striking miners at Lena River.

By mid-1914 the number and intensity of industrial strikes were approaching 1905 levels. Fed up with low wages and dangerous conditions, workers at the remote Baku oil field walked out in June. When news of this reached St Petersburg it triggered worker unrest there; the capital was hit by 118 strikes in June alone. At the beginning of July, around 12,000 workers from the Putilov steel plant – the same factory at the heart of the ‘Bloody Sunday’ protests – marched in the capital, where they were fired on by tsarist soldiers. Two were killed and dozens injured but the government’s response was to deny the incident happened.

This culminated in the great general strike of July 1914, which paralysed more than four-fifths of St Petersburg’s industrial, manufacturing and commercial plants. One right-wing newspaper described the situation as revolutionary, saying “We live on a volcano”.

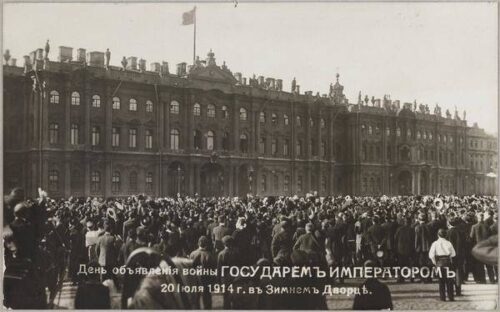

Days after the Russian declaration of war, Nicholas II and Alexandra – ironically of German birth herself – appeared on the balcony of the Winter Palace, to be greeted by thousands of people on bended knees. When conscription orders were distributed in the capital, more than 95 per cent of conscripts reported willingly for duty. The tsar too was changed by the events of August 1914. In the months prior he had shown little interest in the affairs of state, but both the war and the revival of public affection reinvigorated Nicholas, who threw himself into his duties.

“Right from the beginning of hostilities I have never been able to find out anything about our general plan of campaign. [Years before] I was acquainted with the general plan in event of war with Germany and Austro-Hungary. It was strictly defensive and in my opinion ill-conceived from many points of view, but it was not put into execution because the circumstances forced us into an offensive campaign for which we had no preparations. What was this new plan? It was a dead secret to me. It is quite possible that no new plan was ever established at all, and that we followed the policy determined by our needs at any given moment.”

General Brusilov

The Russian army’s shortfall of equipment was compounded by poor leadership from its generals and officers. The army began an invasion of German East Prussia in the first month of the war but was defeated at the Battle of Tannenberg (August 1914).

By the autumn of 1915, an estimated 800,000 Russian soldiers had died, yet the Russian army had failed to gain any significant territory. Public morale and support for the war were dwindling; Russians became more receptive to anti-war rhetoric and propaganda, much of it disseminated by the growing Bolshevik movement.

In August 1914 the Russians were forced to order a massive retreat from Galicia and Poland. The outraged tsar made a telling error, removing his army commander-in-chief, Nicholas Nicholaevich, and taking command of the army himself. Nicholas’ generals and several of his civilian advisors opposed this move. They reminded the tsar that his military experience was confined to cavalry training; he had no practical experience of strategic warfare or commanding infantry and artillery in combat. But the tsar, bolstered by encouragement from his wife, proceeded to the front.

Two years of war also had a telling impact on Russia’s domestic economy. The conscription of millions of men produced a labour shortage on peasant landholdings and a resultant decline in food production. Large numbers of peasants were also moved to the industrial sector, which generated a slight rise in production but nowhere near enough to meet Russia’s war needs. The war placed Russia’s transportation system under enormous strain, as engines, carriages and personnel were redeployed to move soldiers and equipment to and from theatres of war. Inadequate maintenance and replacement of this infrastructure caused it to fail. By mid-1916 an estimated 30 per cent of Russia’s railway stock was unusable. This had a severe impact on Russia’s cities, which relied on railway shipments for their supplies of food and coal. Short of reserves to fund the war effort, the government resorted to printing excess paper currency, which in turn led to inflation. By late 1916 inflation had reached almost 400 per cent.

1. Russia entered World War I in August 1914, after promising support to its Balkan ally Serbia against Austria-Hungary.

2. The war doused anti-government sentiment which had peaked with a general strike in St Petersburg in July 1914.

3. Russia’s first military forays were disastrous: its soldiers were poorly equipped, its officers barely competent.

4. In September 1915 the tsar took command of the army, a move that associated him with future defeats and losses.

5. By mid-1916, two years of war had decimated the Russian economy, triggered downturns in agrarian production, problems in the transportation network, currency inflation and food and fuel shortages in the cities.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Russia in World War I” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/world-war-i/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].