During the early 19th century Russia developed trade relationships with other European countries and exported large amounts of grain. But most of the export revenue that flowed into the empire simply lined the pockets of aristocrats and powerful land-owners; it was not used as capital to develop an industrialised economy. Industrial projects and incentives were often proposed – but they were rarely embraced since they threatened the financial interests of conservative landowners. There was some heavy industry – mining, steel production, oil and so on – but this was small when compared to Russia’s imperial rivals: Britain, France and Germany.

It took defeat in the Crimean War (1853-56) to expose the empire’s lack of development and the urgent need for Russian industrialisation. Russian factories were unable to produce sufficient amounts of weapons, munitions or machinery. There was very little technical innovation; most of Russia’s new technologies were imported from the West. And the empire’s railway system was woefully inadequate, with insufficient rail lines and rolling stock to move men or equipment in large amounts.

One of the anticipated outcomes of 1861 was the emergence of a successful peasant class, the kulak. The kulak would be proto-capitalist: he would own larger tracts of land and more livestock or machinery; he would hire landless peasants as labourers; he would use more efficient farming techniques; and he would sell surplus grain for profit. But while the 1861 emancipation did release millions of peasants from their land, the strength of peasant communes prevented the widespread development of a kulak class.

The emancipation had significant social outcomes but it failed to contribute much to Russia’s economic development. In the 1870s the government initiated several large infrastructure programs, particularly the construction of railways. The 1880s saw the emergence of Sergei Witte, a qualified mathematician with a proven track record of achievement, both in the tsarist bureaucracy and the private sector. In 1889 Witte was placed in charge of the Russian railway system, where he oversaw the planning and construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

By 1892, Witte was minister for transport, communication and finance. Identifying a need for capital investment, Witte made it easier for foreigners to invest in Russian industrial ventures. Existing barriers were removed, while foreign individuals and companies were offered incentives if they invested in certain industrial and manufacturing sectors. Witte also undertook currency reform: in 1897 he moved the Russian rouble to the gold standard, strengthening and stabilising it and improving foreign exchange. He also borrowed to fund public works and infrastructure programs including new railways, telegraph lines and electrical plants.

“The state participated directly in the nation’s economy to an extent unequalled in any Western country. In 1899 the state bought almost two-thirds of all Russia’s metallurgical production. By the early 20th century it controlled some 70 per cent of the railways and owned vast tracts of land, numerous mines and oil fields, and extensive forests. The national budgets from 1903 to 1913 indicated that the government received more than 25 per cent of its income from various holdings. Russia’s economic progress in the eleven years of Witte’s tenure as minister of finance was, by every standard, remarkable. Railway trackage virtually doubled, coal output in southern Russia jumped from 183 million poods in 1890 to 671 million in 1900.”

Abraham Ascher, historian

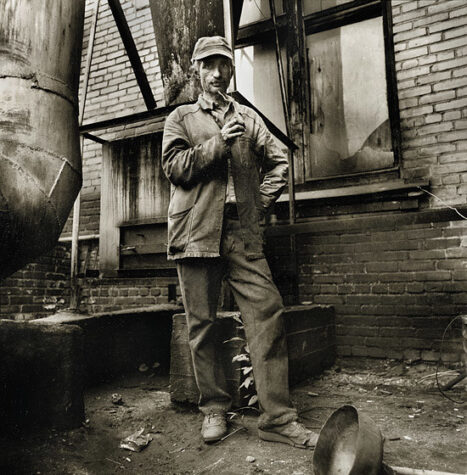

But for all its advances, the economic transformation of Russia also delivered unforeseen consequences, some of them problematic for the regime. The construction of new factories drew thousands of landless peasants into the cities in search of work. In time, they formed a rising social class: the industrial proletariat.

Russia’s cities were not equipped for the rapid urban growth that accompanied industrialisation. In the early 1800s only two Russian cities (St Petersburg and Moscow) contained more than 100,000 residents; by 1910 there were twelve cities of this size. In the decade between 1890 and 1900, St Petersburg swelled by around 250,000 people. This growth was not matched by the construction of new housing, so industrial employers had to house workers in ramshackle dormitories and tenements. Most lived in unhygienic and often freezing conditions; they ate meals of stale bread and buckwheat gruel (porridge) in crowded meal-houses.

Things were even worse in the factories, where hours were long and the work was monotonous and dangerous. Witte’s economic reforms had met, even exceeded national goals – but they also gave rise to a new working class that was exploited, poorly treated, clustered together in large numbers and therefore susceptible to revolutionary ideas.

1. For much of the 1800s, Russia was a comparatively backward economy, dominated by agrarian production.

2. Defeat in the Crimean War triggered reforms, such as the abolition of serfdom to facilitate a mobile labour force.

3. The main instigator of economic reform was Sergei Witte, who attracted foreign investment in Russian industries.

4. Witte’s changes triggered a marked growth in industrial production and the movement of workers into the cities.

5. In economic terms, the policy reforms were successful and helped Russia ‘catch up’ to western European powers – but they also created an industrial working class prone to grievances and revolutionary ideas.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Russian industrialisation” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/russian-industrialisation/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].