The Provisional Government inherited political authority after the abdication of Nicholas II. It enjoyed a brief honeymoon period marked by hope, optimism and public support. But the Provisional Government was soon confronted by the same policy issues that had undermined and destroyed tsarism. The abdication of Nicholas II might have relaxed the mood of the people – but it did not bring bread or coal into Petrograd. Even more pressing was the question of Russia’s involvement in World War I. Many argued that it should seek peace terms from Germany and withdraw from the war, to ease pressure on its economy and people and to manage its political reformation. Others believed that Russia, having made promises to its allies in 1914, should honour them. The Provisional Government chose the latter path, a decision that eventually proved fatal. By the end of July 1917, the Provisional Government was disregarded, disrespected and almost powerless. The question was not whether it would survive but when it would fall.

1. An immediate and complete amnesty in all cases of a political and religious nature, including terrorist acts, military revolts and agrarian offences, etc.

2. Freedom of speech, press, and assembly, and the right to form unions and to strike and the extension of political freedom to persons serving in the armed forces limited only by the demands of military and technical circumstances.

3. The abolition of all restrictions based on class, religion, and nationality.

4. The immediate arrangements for the calling on the Constituent Assembly on the basis of universal, equal and direct suffrage and secret ballot, which will determine the form of government and the constitution of the country.

Though its members were drawn from the Duma, the Provisional Government had no mandate; it had not been selected or endorsed by the people. Russians were aware that it was a temporary government, so its laws and decrees were not always respected or taken seriously. As the year progressed, the Provisional Government found it more and more difficult to see its policies through to completion. By the summer the government was largely impotent and its most of its directives were carried out partially or half-heartedly, if at all. One contemporary observer dubbed it the “Persuasive Government”, since it had to cajole or convince to get things done.

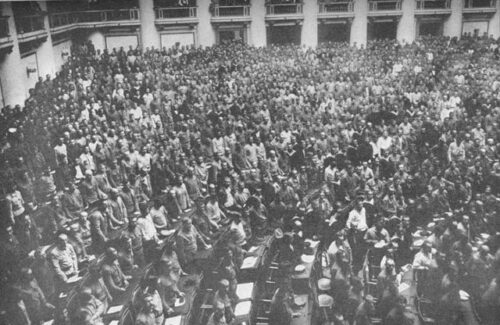

A significant factor in the Provisional Government’s weakness was the rise of another body: the Petrograd Soviet. A reincarnation of the old St Petersburg Soviet of 1905, the Petrograd Soviet came together in the final days of the February Revolution. It began as a rowdy meeting of militant workers and soldiers but within days had become a representative council, containing delegates from almost every factory, workplace and military unit in the capital. At its peak, the Petrograd Soviet boasted more than 3,000 members. While its meetings were loud and boisterous, the Soviet’s political aims were initially moderate. Its executive council (Ispolkom) and daily newspaper (Izvestia) were dominated by Mensheviks and moderate Socialist-Revolutionaries. In its first weeks the Soviet harboured very little talk of overthrowing or replacing the Provisional Government – but it was more divided on the question of war, with a sizeable number of its delegates supporting Russia’s immediate withdrawal.

One of the Petrograd Soviet’s first and most meaningful resolutions was its famous Order Number One, issued two days prior to the abdication of the tsar. This order called on all military units to maintain discipline and readiness – but to seek the approval of the Soviet before carrying out any orders issued by the State Duma. It was passed to reduce the chances of an armed counter-revolution, either from the tsarist regime, its generals or conservatives in the Duma.

Order Number One is often interpreted as an attempt to undermine the Provisional Government; this is not the case, as the Provisional Government had not yet been formed. But the order clearly demonstrated the Soviet’s willingness to ignore or countermand orders given by civilian authorities, if they conflicted with the interests of workers and soldiers. This set the scene for what was later known as the ‘Dual Power’: the eight months of 1917 when political control was divided between the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet. As Kerensky later put it, the Soviet possessed “power without authority” while the Provisional Government had “authority without power”.

“While the Provisional Government was losing power, the Soviets spread rapidly throughout Russia, reaching not only large industrial centres but also local towns and rural districts. The Soviets were unruly and in themselves posed no direct threat to the government’s existence. That situation changed when the Bolsheviks began to dominate an increasing number of Soviets, particularly in large towns and industrial centres. Since the Bolsheviks were eager to gain power by force, the Provisional Government was doomed. The giant Russian Empire was like a minor post-colonial state: a few dozen armed and determined men could stage a coup d’etat without encountering serious resistance.”

Christopher Lazarski, historian

While these arguments had some merit, the decision to sustain the war effort drove a wedge between the Provisional Government and the people. It also produced significant changes in the government itself. In mid-April, foreign minister Pavel Milyukov penned a telegram to the Allies, informing them that Russia would remain in the war until its conclusion. Milyukov’s telegram was leaked to radical socialists and then the press, which triggered large public demonstrations in Petrograd. Facing enormous public pressure, Milyukov and war minister Alexander Guchkov were forced to resign. Guchkov was replaced by Kerensky, who was joined in the cabinet by six other socialist ministers. Kerensky had learned no lessons from the April unrest or the fate of his predecessors, however. Two months after his appointment as war minister, he ordered an ambitious new offensive against the Austro-Hungarians in Galicia. Kerensky toured the frontline, worked closely with military commanders and gave rousing speeches – but these ploys had little effect. The Russian army was fatigued by three years of war, still poorly led and under-resourced and pushed to the brink of mutiny by anti-war propaganda. The July Offensive in Galicia was a costly defeat, resulting in 400,000 casualties. Kerensky’s only response was to sack his commander-in-chief, Brusilov, and replace him with General Lavr Kornilov – a move that would soon have consequences for Kerensky’s government.

1. The Provisional Government was formed in March 1917 from a temporary committee of Duma deputies.

2. Its mission was to manage Russia’s transition from tsarism to a democratic government through an elected Constituent Assembly.

3. The government had no mandate and exerted little power. Most followed its orders only when they were acceptable.

4. The Petrograd Soviet, a representative council of 3,000 delegates, also challenged the government’s authority.

5. The most pressing concern for the Provisional Government was its decision to maintain the war effort. This made the government extremely unpopular, particularly in April (forcing the resignation of Milyukov) and again in July (after Kerensky’s failed offensive in Galicia).

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Provisional Government” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/provisional-government/, 2014, accessed [date of last access].