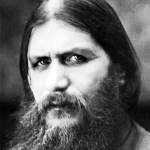

The Siberian-born starets Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (1869-1916) was one of the tsarist regime’s most notorious figures. Arriving in Saint Petersburg in 1903, Rasputin formed connections with members of the high clergy and, later, Nicholas II and his family. He would spend the next decade ingratiating himself with the Romanovs, political leaders and aristocrats, exerting influence and trading favours for his own gain. Rasputin was also notorious for his coarse manners and sexual habits. A reactionary clique murdered Rasputin in December 1916, a belated attempt to protect the monarchy from his malignant influence. In the days that followed, the Russian press had the following to say about his life and death:

The Siberian-born starets Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (1869-1916) was one of the tsarist regime’s most notorious figures. Arriving in Saint Petersburg in 1903, Rasputin formed connections with members of the high clergy and, later, Nicholas II and his family. He would spend the next decade ingratiating himself with the Romanovs, political leaders and aristocrats, exerting influence and trading favours for his own gain. Rasputin was also notorious for his coarse manners and sexual habits. A reactionary clique murdered Rasputin in December 1916, a belated attempt to protect the monarchy from his malignant influence. In the days that followed, the Russian press had the following to say about his life and death:

From the middle-class newspaper Dien:

“Grigori Rasputin was a personage about whom… there has been a deal of talk in Russia and the whole of Europe during the last few years. The influence popularly ascribed to him has tempted more than one who knows Russia to profound reflections…

The extent of Rasputin’s influence on our Russian life today cannot possibly be described at the present moment. Undoubtedly his influence has been amazingly great, particularly in the ecclesiastical sphere. A certain explanation of Rasputin’s rise in society is afforded by the company with which he used to surround himself, particularly when travelling. All wives (!), daughters and sisters belonging to the most fashionable society used to call him ‘Father’.”

From the Kadet newspaper Retsch:

“There are persons with whom he has had features in common but he distinguished himself from them all by his stubbornness and impudent interference in all affairs of state. He applied by his letters – despite being well aware that he was hardly able to write – to acquaintances, strangers, ministers of the government and bank directors. He took it upon himself to forward petitions in all possible concerns and he let nothing stand in the way of his carrying through what he had set his mind on.

His influence steadily increased. Persons of high standing sought his favour. It is often asserted that Protopopov visited him daily but the latter was by no means the only one. People had recourse to him on all and every occasion. There was nothing that might not be asked of him…

That he should end his days as he did was not difficult to foresee. But the importance lies in the fact that it was not so much Rasputin himself but this milieu he had created, which made it possible for him to play such a unique part [that] people were constrained to speak of the influence of ‘dark powers’.”

From Russkiye Vedomosti, a liberal-conservative paper based in Moscow:

“The man of whom so much has been talked of late… [The man] in whom people saw the first weapon of the ‘dark powers’, if not always its source… this man is slain. He fell not by the act of a revolutionary but by the hands of persons who stand on the highest grades of society.

In all this weird and obscure affair lies the most striking and – we may openly say it – the most humiliating offence to our political and national dignity: the sharp contrast between the murdered man’s insignificance and character on the one hand and, on the other, the unprecedented impression that news of his death made all over Russia.

Future historians will pause with amazement at the fact that in the period of the Great War, when thousands of noble lives were sacrificed for the mother country, the whole attention of Russia was taken up by the question as to whether this person was dead or alive… Under conditions that prevail with us, the drama in Petrograd comes to be not a sensational romance but an event of real significance.”