By the end of 1905, Russia boasted several major groups or parties desiring political reform. The events of 1905 served as a catalyst for this. In February the tsar ordered the relaxation of laws governing political censorship, publication and assembly. This unleashed a tsunami of political propaganda, publications and documents, as well as the organisation of scores if political meetings. Groups once forced to meet illegally or semi-legally could now gather openly, form political parties, draft party manifestos and produce propaganda for public consumption. Not all these Russian political parties were Marxist or socialist. Some wanted Russia to develop into a liberal democracy, underpinned by a constitution, a constituent assembly and individual rights and freedoms. Others believed the promises laid out in the October Manifesto went far enough.

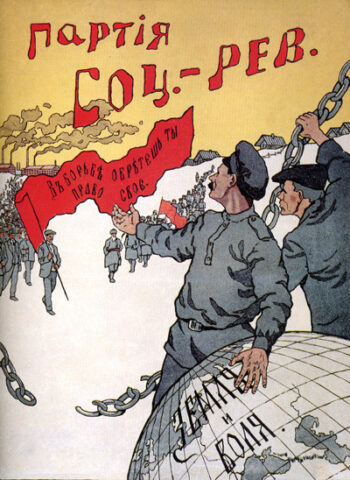

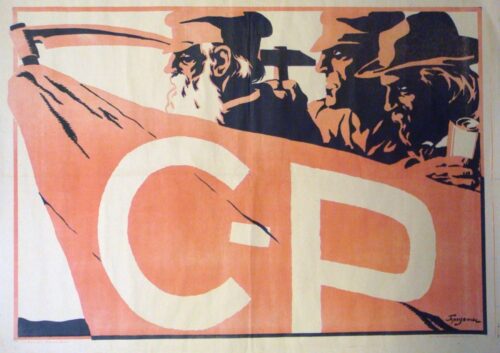

The Social Democrats (SDs) were Russia’s largest Marxist party but not its largest socialist party. That honour went to the Socialist-Revolutionaries, a group often referred to as the SRs or ‘Esers’. Formed in Kharkov in 1900 from a coalition of populist groups, the SRs soon became the largest political organisation in Russia. As its name suggests, the party was explicitly revolutionary: it called for the removal of the tsarist government – or radical reforms at the very least. The SR party platform was socialist but non-Marxist: its agenda lacked the complicated political philosophy of Marxism and had little interest in world revolution. The SR focus was instead on Russia, particularly on the fate of its peasantry. Agrarian policy and land reform were the cornerstones of SR policy. Its members called for ‘land socialisation’: the abolition, confiscation and equitable redistribution of large landholdings, especially those owned by the tsar and his nobles. These promises of land reform, along with their simpler philosophy and policy positions, saw the SRs become the most popular political party with Russian peasants.

“The Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party is one of the losers of history. As a result of the October Revolution of 1917, it was driven from power by the Bolsheviks and soon banned. The party leaders were degraded to ‘yesterday’s people’ and had to emigrate… Nevertheless the downfall of the SRs should not obscure the great importance of this party in the Russian revolutionary movement.”

Manfred Hildermeier

The 1905 Revolution produced changes in the party structure. The core of the party became more moderate and began to function as a legitimate political party, while the assassins and terrorists were pushed to the party’s fringes. The SR leadership suspended all terrorist activity after the publication of the October Manifesto. The party began to receive support from the middle-classes and trade unions. The SRs boycotted the first state Duma in 1906, despite having 34 party members elected as deputies; they participated in the second Duma in 1907 but again boycotted the third and four Dumas, in the wake of Stolypin’s electoral rigging.

The size of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party should have been its strength – but it instead became a weakness. With such a large membership and diversity of positions, the SRs struggled with party unity and cohesion. Sections of the party disagreed and bickered over whether to stand candidates in the Duma, whether to support or oppose the war, what to do about the Provisional Government. The party’s moderate core, referred to as Right SRs, were led by Victor Chernov, who later in the Provisional Government as a minister. Its radical faction, the Left SRs, were led by Maria Spiridonova, a former terrorist who once murdered a tsarist official by shooting him in the face. Alexander Kerensky, the first socialist minister in the Provisional Government, belonged to the Trudoviks, another SR faction. After 1905 these fractures in the SR party widened further, chiefly over disagreements about the war, and by late 1917 the party was irrevocably split. Despite this schism in their party, the SRs retained peasant support and won a small majority in the Constituent Assembly elections of November 1917.

The Kadets

“The core of the Kadets’ message [in the election of 1905] was that they deserved the people’s support because they alone defended the true interests of the country. Their appeals contained alluring promises and dire predictions about the country’s fate, should the conservatives win. ‘The future of Russia depends on the result of these elections. If they produce a constitutional and democratic majority, Russia will enter the path of peaceful cultural, political and social life. If they produce a majority that is not for decisive reform, then civil war, shooting and blood will inundate Russia, will grow and spread, producing anarchy in the economic life of the country.'”

Abraham Ascher, historian

Most Kadets favoured the development of a British-style political system, with the tsar remaining as the head of state but his political authority constrained by a constitution and an elected constituent assembly. The Kadets also pushed for the introduction of Western-style civil rights and liberties: equality before the law, universal suffrage for men and women, an end to hereditary noble titles, free and universal state education, official recognition of trade unions and legislation protecting the right to strike. They also objected to state censorship of the press. Their liberal policies made the Kadets popular in the cities and larger towns. In the wake of the 1905 Revolution, they recorded 37 per cent of the urban vote in elections for the State Duma, ending up with about one-third of the seats.

Also represented in the Duma from 1906 were the Octobrists. More conservative than the Kadets and generally loyal to tsarism, the Octobrists derived their name from the October Manifesto, a document they enthusiastically endorsed as the solution to Russia’s problems. The Octobrists supported a limited constitutional monarchy, private farming, the reactionary policies of chief minister Peter Stolypin and the continuation of the Russian Empire. They did not share the Kadet desire for improvements to civil rights, education and union legalisation. After Stolypin rigged voting for the 1907 Duma elections, the Octobrists became the largest faction in the Third Duma (1907-1912). Like the Kadets, the Octobrists supported Russia’s war effort during World War I, a policy that cost them some support. Several Octobrists occupied some key government positions during the war and the Dual Power of 1917. Probably the most notable was Mikhail Rodzianko, who served as chairman of the Duma and was instrumental in convincing Nicholas II to abdicate in March 1917.

1. Russian political parties emerged from the shadows after censorship laws were relaxed in 1905.

2. The SRs sought land reform and changes to agrarian policy, a position that made them popular with peasants.

3. The large size of their party, however, invited differences of opinion, divisions and factionalism.

4. The Kadets were the largest liberal-democratic party, favouring a British-style constitutional system.

5. The Octobrists were moderates and conservatives who were loyal to tsarism and supportive of the changes outlined in the October Manifesto.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Other Russian political parties” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/other-russian-political-parties/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].