In the evening of October 25th, Bolshevik Red Guards moved on government positions around the city of Petrograd. They then invaded the Winter Palace, where several government ministers were resident. Within hours, the Provisional Government had been deposed and its members had either fled or been arrested. The armed seizure of power was organised and conducted by the Bolsheviks, acting the name of Russia’s Soviets. But it soon became apparent that the Soviet revolution was actually a Bolshevik revolution; that Lenin and his fellow radicals had no interest in sharing power with Mensheviks or moderates, who they condemned to the “dustbin of history”. The October Revolution was a pivotal event in world history with effects that reverberated through the 20th century. It plunged Russia into years of unrest, civil war, terror and famine.

The push for an immediate seizure of power came from Lenin. The Bolshevik leader remained in hiding in Finland through September – but he penned a torrent of letters to his colleagues urging them to overthrow the Provisional Government as soon as possible. To delay would be fatal, Lenin argued, offering a range of scenarios. Kerensky may submit to another Kornilov and impose martial law; support for the Bolsheviks may peak and tumble; Petrograd may even fall to the Germans. Within the Bolshevik hierarchy, there was some opposition to this urgent call for revolution. Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev both dismissed Lenin’s arguments as panicked. Their preferred course of action was to push for the immediate election of the Constituent Assembly, where the Bolsheviks could best exploit their rising support. Lenin’s call for revolution was premature, they argued, and would create a Bolshevik government that was fragile, surrounded and unlikely to survive. The majority of Bolsheviks preferred to wait until the second Congress of Soviets, scheduled for late October.

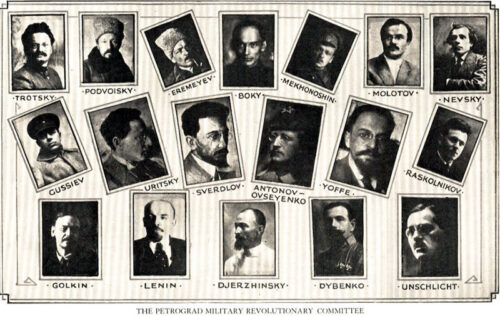

Three weeks before the congress, the Petrograd Soviet accepted a resolution by Trotsky, calling for the formation of a Military Revolutionary Committee (Milrevcom or MRC). The committee’s purported function was to organise and oversee the Red Guards, as a means of defending Petrograd and the Soviet from a military coup or counter-revolution. Milrevcom was populated by Bolsheviks and radical Left SRs, while Trotsky became its chairman and de facto leader. Through the middle of October, Trotsky and others worked to arm Red Guard units and bring them under the control of Milrevcom. Very little of this was a secret: the activities of Milrevcom were openly reported in left-wing newspapers around Petrograd. The Provisional Government’s failure to act astonished many, including British ambassador Sir George Buchanan, who wrote that he “could not understand how a government that respected itself could allow Trotsky to go on inciting the masses to murder and pillage without arresting him”.

The Bolshevik revolution was started by Kerensky rather than by a bold order given by Lenin or Trotsky. In the early hours of October 24th, Kerensky ordered troops loyal to the government – by this stage a regiment of cadets and reservists – to take action against Bolshevik activists. Armed with arrest orders for Trotsky and other Milrevcom members, they raided buildings where Bolshevik propaganda was being produced, destroying newspapers and seizing or sabotaging their printing presses. Telephone lines to the Bolshevik headquarters at the Smolny Institute were cut, however, news quickly reached the Smolny. Trotsky and the Milrevcom interpreted the government’s move as the first step in a right-wing counter-revolution: “A treasonous against the Petrograd Soviet… is being planned”. Even at this last hour there was division in Bolshevik ranks about how to proceed. Some, believing the Provisional Government to be stronger than it seemed and still able to call on loyal army units, argued that Milvrecom should undertake preparation and consolidation of military forces, instead of launching an armed insurrection. At the same time Kerensky, who was anticipating a Bolshevik response, attempted to rally political and support for the government, though with little success.

Legend has invested the events of October with heroic stature. They are presented as an epic frieze across which move figures possessing dimensions greater than life. Above them towers the commanding presence of Lenin, the leader, the master strategist, all wise, armed with the guiding truth of Marx… [In reality] the October events were encumbered by trivia, petty rivalry, miscalculation, hesitation, ineptitude, posturing and mistakes. Almost nothing was planned and what did happen was accidental. The Bolsheviks did not seize power in one bold clandestine move; they blundered into power, divided and fighting against each other. And until the final moments, Lenin had only an occasional role in what had happened.

Harrison Salisbury, historian

The takeover of Petrograd began on the morning of October 25th. It coincided with Lenin’s return to the Smolny, after weeks in hiding. Kerensky too was on the move, speeding from the Winter Palace in a car and making his way to the frontline, in a desperate mission to recruit troops to defend the government. Through the course of the day, Red Guards and troops loyal to the Soviet moved on and captured critical installations and infrastructure: government buildings, armouries, telegram stations, bridges and thoroughfares. The most significant prize, of course, was the Winter Palace, which had become the seat of the Provisional Government and a residence for many of its ministers and functionaries. The Winter Palace was loosely defended by around 3,000 officers, cadets, reservists and Cossacks. American journalist John Reed managed to sneak into the palace on the afternoon of October 25th, reporting that its defensive garrison was drunk, hungry and miserable. Meanwhile, revolutionary forces gathered outside, surrounded the palace and awaited orders to attack.

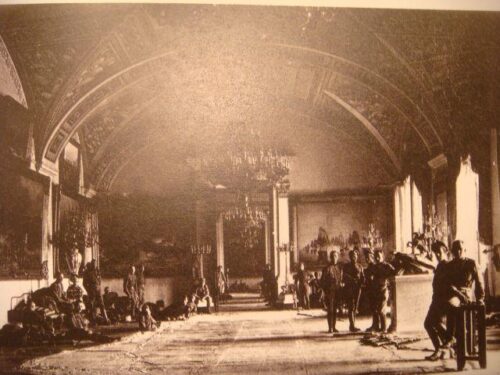

The order finally came in the evening. At 9.45pm sailors from the Kronstadt naval depot fired a blank shell from the cruiser Aurora, a signal to begin the assault. The palace was bombarded with artillery from across the Neva River, while Red Guards began firing on the building’s defensive positions with small arms. The militia and cadets inside the palace compound had little appetite for the fight: many abandoned their positions and either fled the scene or joined up with their attackers. As Bolshevik forces rushed through the palace’s entry points, Provisional Government ministers cowered in an upstairs dining room and awaited the inevitable. They were arrested four hours after the attack began, a delay worsened by the time it took to search the palace’s 1,500 rooms. Some Red Guards units went on an orgy of destruction in parts of the palace, destroying valuable art, crystal, china and glassware. The living quarters of the former tsarina, Alexandra, came in for particularly destructive treatment.

Meanwhile, as the guns were ringing out across Petrograd, the second Congress of Soviets was getting underway in the great hall at the Smolny. The Bolsheviks had around 300 delegates, their Left SR allies approximately 80; this gave them a small majority in the 670-delegate congress. But the meeting began with a flurry of speeches from Mensheviks and moderate SRs, condemning the Bolsheviks for seizing power illegally. This presumptive action, they said, would incite a military counter-revolution that threatened the future of the revolution and the Constituent Assembly. After some furious debate then some attempts at reconciliation, the Mensheviks and other moderates walked out of the congress in protest at the insurrection and the Bolshevik refusal to compromise. It was a fatal error since it left the Soviets almost entirely in Bolshevik hands. They continued their meeting for several hours, occasionally interrupting proceedings to receive good news, such as reports that the Winter Palace had been taken. Shortly before dawn, the following resolution, written earlier by Lenin (who was not yet present at the congress) was adopted with almost no opposition:

The Soviet government will propose an immediate democratic peace to all the nations and an immediate armistice on all fronts. It will secure the transfer of the land… to the peasant committees without compensation; it will protect the rights of the soldiers by introducing complete democracy in the army; it will establish workers’ control over production; it will ensure the convocation of the Constituent Assembly… it will see to it that bread is supplied to the cities and prime necessities to the villages; it will guarantee all the nations in Russia the genuine right to self-determination. The Congress decrees that all power in the localities shall pass to the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies.

1. On October 25th the Bolsheviks captured Petrograd and the Winter Palace, arresting the Provisional Government.

2. This was triggered by Kerensky’s attempt to silence Bolshevik propagandists and leaders on October 24th.

3. The takeover was carried out by sympathetic soldiers and sailors, Red Guards and the Trotsky-led Milrevcom.

4. Lenin had earlier led the push for a revolution to remove the Provisional Government, against some opposition.

5. Moderate non-Bolsheviks later walked out of the Congress of Soviets, leaving it in the hands of the Bolsheviks.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The October Revolution” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/october-revolution/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].