The Lena River is one of the longest watercourses in the world. It flows almost 3,000 miles through north-east Siberia and into the Arctic Ocean. The Lena occupied one of the most remote regions in the Russian empire – but it also contained substantial mineral resources. In the early 1900s, a group of wealthy Russians and Britons purchased shares in a company planning to mine gold from the area. Some of these investors included the dowager empress (the tsar’s own mother) and several other members of the royal family, as well as the former chief minister Sergei Witte and Putilov, the steel-factory mogul. The company, Lena River Mining, began drilling and excavation near the town of Bodaybo, 2,000 miles to the northeast of Irkutsk. Several thousand Russian workers were hired and transported to the mine, most of them from outside Siberia.

The company’s manipulation of supplies was another source of worker unrest. The Lena River miners were reliant on the company for supplies of food, vodka, clothing and other necessities. These commodities were purchased from canteens owned and operated by the company, a standard practice on mining sites in remote areas. Company prices, however, were exorbitantly high, while the goods themselves were often sub-standard. In 1911 the company reduced the cash wages of workers and declared that it would instead pay a sizeable portion of their salary in canteen coupons, essentially forcing them to shop at the canteens. In late February 1912, the food canteen attempted to distribute rotten horse meat disguised as beef. This, on top of other long-standing grievances, sparked a spontaneous but widespread strike amongst the miners.

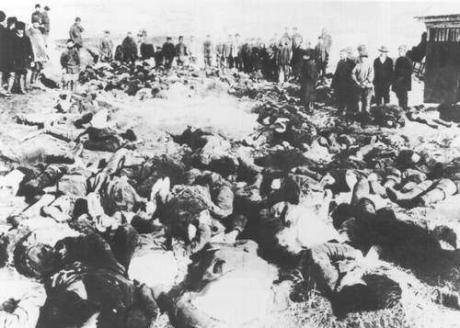

Within four days, 6,000 miners had formed a strike committee and handed the company a set of demands. They included the introduction of an eight-hour day, a significant increase of wages, the abolition of company fines, caps on food prices in the canteens as well as improvements in the quality and delivery of food delivery. The company flatly rejected these demands. The strike continued for weeks into March, freezing production. The company requested a detachment of troops from the government. The troops arrived in early April and immediately arrested the leaders of the miners’ strike committees. This led to even more unrest in surrounding goldfields not yet affected by the strike. On April 5th a crowd of around 2,500 workers marched on company headquarters, demanding the release of their compatriots. They were confronted by a brigade of soldiers who were given orders to fire on the mob, killing around 250 men and injuring a similar number.

“Into a deceptive calm burst the news of the Lena shooting. The Lena massacre soon became the empire’s major story, supplanting the sinking of the Titanic that occurred at the same time… Readers of the press could hardly avoid the issue. The State Duma plunged into a heated discussion, as several political parties offered angry interpellations filled with accusations against the government… Russian society reacted furiously and, in a certain way, unexpectedly to the slaughter on the distant Lena River.”

Michael Melcanon, historian

1. The Lena River goldfields were located in remote Siberia and funded by wealthy Russian and English investors.

2. Miners at Lena River endured long working hours, unsafe conditions, company fines and over-priced supplies.

3. In 1912 around 6,000 miners went on strike after being supplied with rotten horse meat in the company canteen.

4. Their demands for improved conditions were rejected by the company, which called in government troops.

5. The arrest of strike leaders triggered more unrest and led to the killing of around 250 miners by the troops. The Lena River massacre reignited anti-tsarist tensions and led to a wave of strikes, particularly in St Petersburg.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Lena River massacre” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/lena-river-massacre/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].