In the first days of July 1917, a spontaneous uprising erupted in Petrograd. The July Days, as this uprising became known, was fuelled by several factors: the Provisional Government’s attempt to escalate the war effort, a collapse in the government ministry and a constant stream of Bolshevik propaganda condemning the government and calling for a transfer of power to the Soviets. By the beginning of July, thousands on the streets of Petrograd thought the time had come for a Soviet revolution. Most were disgruntled factory workers, soldiers and sailors; many were card-carrying members of the Bolshevik party. But when they made their move on July 3rd, neither the Soviet nor the Bolshevik hierarchy was prepared to take command of the uprising. Starved of leadership, the July uprising dwindled and failed. Rightly or not, the Bolsheviks were held responsible for the uprising, their leaders arrested, driven into exile and targeted by hostile government propaganda. By late July 1917, the Bolshevik movement seemed to have been defeated.

The slaughter continues and there is an industrial collapse in the making. We see the rich lining their pockets from this criminal war and we sense and know that a sinister and terrible famine is approaching. We also see the jackals from the State Duma and State Council reaching out with their filthy paws to strangle freedom. The rights of the soldier are falling by the wayside; so is the reinforcement of the rights of freedom… We hotly protest any kind of bourgeois ministry and we demand that the ten bourgeois [ministers] make way. We demand that the All-Russian Soviet of Soldiers’, Workers’ and Peasants’ Deputies seize all power.

A dangerous situation was made worse by a disastrous military offensive. It was authorised in mid-June by Alexander Kerensky, since been ‘promoted’ to the Provisional Government’s war minister. In mid-June Kerensky approved a massive assault on Austro-Hungarian defences in Galicia. Kerensky’s decision to attack seems to have been motivated by the arrival of dozens of heavy artillery pieces from Britain and Japan; he also hoped to improve morale, both in the ranks of the army and in Russia generally. The first two days of the ‘Kerensky Offensive’, as it became known, was more successful than not, as the Allied guns blasted openings in the Austro-Hungarian defences that allowed Russian infantrymen to make early advances. But the offensive soon encountered stronger resistance from German units and began to collapse. By mid-July the Russians had suffered 400,000 casualties and were forced to retreat, surrendering more than 200 kilometres.

News of the offensive was met with anger and hostility in the cities. Perhaps aware of the oncoming crisis, the Provisional Government’s coalition ministry collapsed, triggered by the resignation of prime minister Lvov and all four Kadet ministers. News of the disastrous offensive, along with the implosion of the government, sparked unrest in Petrograd not dissimilar to the events of February.

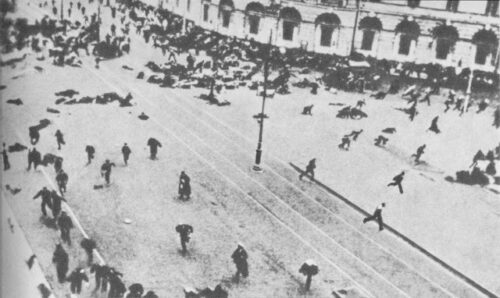

On the evening of July 3rd, street demonstrations and riots involving thousands of factory workers broke out in the capital. The following day they were joined by mutinous soldiers from the Petrograd garrison, as well as sailors from the nearby island fortress of Kronstadt (they had earlier taken control of their base, murdering more than 40 officers and establishing their own form of direct democracy). Estimates of their numbers vary: some sources suggest there were 100,000 involved, others more than a half-million. With another revolution seemingly building, the question arose of who would lead it.

One large group assembled outside the Tauride Palace, the meeting place of the Petrograd Soviet, expecting a declaration that the Soviet had assumed power. All they got, however, was the moderate SR leader Victor Chernov, who gave a raft of excuses why the Provisional Government should re-form and continue. Chernov’s equivocation angered the crowd – including one heckler, who famously shouted: “Take power, you son of a bitch, when it is handed to you!”

“One of the most widely circulated post-July Days indictments of the Bolsheviks was written by the famous populist Vladimir Burtsev. On July 6th, in an open letter printed in many papers in Petrograd, he joined the onslaught: “Among the Bolsheviks, provocateurs and German agents have played and continue to play a great role. In regard to the Bolshevik leaders… thanks to them – to Lenin, Zinoviev, Trotsky, etc. [Kaiser] Wilhelm has achieved what he had previously only dreamed about… In those days Lenin and his comrades cost us no less than a major plague or cholera epidemic.”

Alexander Rabinowitch, historian

Lenin eventually appeared before them but his comments were brief, restrained and anti-climactic. The Bolshevik leader offered the crowd neither inspiration, instruction nor his full support. After Lenin finished speaking and withdrew, the deflated mob soon broke up and scattered across the city, many of them resorting to heavy drinking, looting and vandalism. When government forces arrived from the front a day later, they were able to crush the uprising without much opposition. Around 700 people were killed, most of them Bolsheviks or Bolshevik sympathisers; more than a thousand Bolsheviks were arrested.

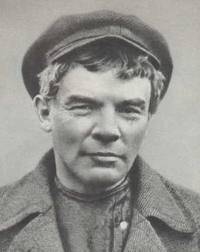

The Bolshevik hierarchy gave the July demonstrations tacit support but refused to back a direct challenge to the Provisional Government. This seems to have been driven by Lenin, who was aware that spontaneous and unplanned revolutions usually failed; he did not trust the unforeseen and was not prepared to stake his political future on a disorganised mob. Some historians put Lenin’s lack of action down to uncertainty. Richard Pipes, a historian ordinarily critical of Lenin’s thirst for power, describes him as a “hopeless vacillator” during the July Days. The outcomes of the July Days, however, are more certain. Responsibility for the uprising was laid squarely at the feet of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, both by the Provisional Government and moderate elements in the Soviet. Kerensky, who in late July was appointed prime minister, took immediate action. He ordered the arrest of Lenin and authorised publication of material claiming that the Bolshevik leader was in receipt of German financial support. Being painted as a traitor eroded Lenin’s popularity and he was forced to flee Russia to Finland, disguised as a fisherman. Hundreds of Bolsheviks were rounded up, imprisoned or forced into exile. With their leaders dispersed and discredited, the Bolsheviks seemed finished – but August was to produce yet another twist in the tale.

1. The July Days was a spontaneous uprising of workers and soldiers in Petrograd in the first week of July 1917.

2. It was sparked by continued opposition to the war, a major offensive in Galicia and the collapse of the government.

3. At least 100,000 gathered in the streets of Petrograd, calling for the Soviets or Bolsheviks to seize power.

4. When both refused to take command of the uprising, it was eventually dispersed and crushed by government troops.

5. The Bolsheviks footed the blame for the July Days uprising, their leaders targeted by government propaganda and arrests, while Lenin was forced to disguise himself and flee to Finland.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The July days” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/july-days/, 2014, accessed [date of last access].