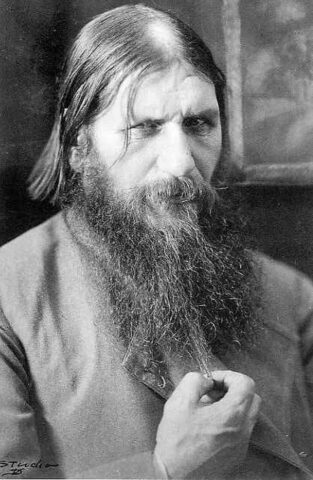

Grigori Rasputin was a Siberian starets (faith healer) who arrived in St Petersburg around 1904 and became an important friend and spiritual advisor to the Romanov royal family. In early 20th century Russia, still dominated by religion and infected by spiritualism and superstition, men like Rasputin commanded enormous interest and respect. Rasputin was a paradox: a holy man in the guise of an unwashed, foul-mouthed peasant. By day he was a spiritual advisor to royals and aristocrats, at night he crawled the streets of the city, guzzling cheap wine and seeking out sexual conquests. That such a creature could work his way into the palaces of the Romanovs was remarkable and worrying enough. But by 1916 Rasputin appeared to many as a malevolent puppeteer, pulling the strings of the tsarina and manipulating the government. He had to be stopped – and stopped he was, though not before bringing considerable shame and discredit to the tsarist regime.

“Ordinary people lined up outside his home every day to ask help in getting an apartment, to request letters of introduction for jobs as clerks, for auditions at theatres, or to beg for help in keeping their sons out of the army. Rasputin could help the little people because the important people he had helped owed him favours. ‘I can do anything’ he said, and because he could get results so often, he was believed. His confidence grew with each success and with it, his ego.”

Ted Gottfried, historian

The Romanovs supplied Rasputin with an apartment in St Petersburg and he became a regular visitor to both the Winter Palace and Tsarskoye Selo. When not with the royal family Rasputin provided spiritual advice – and sometimes sexual services – to at least two dozen upper-class women. When not with them he could be found drinking heavily in the city’s bars and cafes, dancing the kasachok and cavorting with prostitutes.

The situation worsened in September 1915, when the tsar left to take command of the army, asking Alexandra to manage domestic affairs in his absence. The German-born tsarina was already the target of scurrilous rumours that questioned her loyalty to Russia. She was variously accused of selling Petrograd’s food supplies to the Germans through an intermediary; and of having a radio transmitter under her bed so she could communicate with Berlin.

Though there is no concrete evidence of treachery, Alexandra was a political incompetent who was spellbound by Rasputin and prepared to do anything he proposed. Rasputin’s most visible impact on the government was to demand the replacement of ministers, usually to curry favour with his benefactors and drinking partners. Between September 1915 and February 1917 Russia went through four prime ministers, three war ministers and five interior ministers – most of them replaced at Rasputin’s behest. This ministerial leapfrogging destabilised an already foundering government.

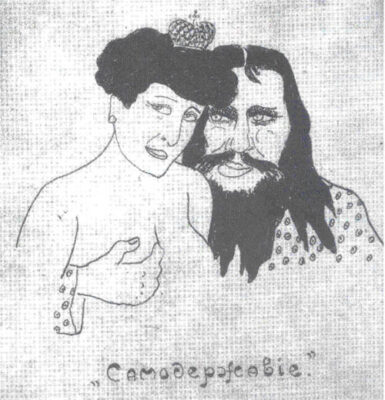

Rasputin was a godsend for socialists and reformists, who pointed to his political interference and lurid nocturnal activities as evidence that tsarism was rotten to the core. Articles and cartoons depicted the tsar under Rasputin’s spell or dancing to his music; coarser examples played on the possibility of a sexual relationship between Rasputin and the tsarina. Consternation about Rasputin was particularly strong in the Duma and among conservative aristocrats, who were fearful that the ‘mad monk’ might single-handedly bring down the dynasty. In late 1916 a trio led by Prince Felix Yusupov, a minor royal, concocted a plan to murder Rasputin as a means of protecting the Romanovs. Rasputin was lured to Yusupov’s Petrograd palace, plied with wine and fed cakes baked with large amounts of cyanide. When this failed to work, the three conspirators stabbed and shot Rasputin then threw his body into the icy Neva River. Rasputin’s murder was intended to save tsarism – but the end of tsarism was already imminent, perhaps even inevitable.

1. Rasputin was a Siberian preacher, spiritual advisor and faith healer who arrived in St Petersburg in 1904.

2. He became a regular counsellor to the tsarina because of his ability to ease the suffering of her haemophiliac son.

3. In time Rasputin won the tsarina’s trust while acquiring a reputation as a notorious drunk and philanderer.

4. From late 1915 he provided Alexandra with political advice, leading to the sacking and turnover of ministers.

5. Rasputin was also the focal point of tsarist propaganda and his presence threatened to bring down the dynasty. As a result, he was assassinated by a conservative clique in December 1916.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Grigori Rasputin” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/grigori-rasputin/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].