Nicholas II’s demise began in February 1917, after two-and-a-half years of total war and more than two decades of dissatisfaction with tsarist rule. Like the unrest of 1905, the February Revolution began spontaneously, a popular revolt rather than an organised insurrection. At the heart of this unrest were shortages of food and fuel. Russian cities had begun to suffer food shortages just months after the outbreak of war. In April and May 1915, both Petrograd and Moscow were paralysed by so-called ‘food pogroms’, as women and workers rioted in protest against the unavailability of meat and bread. But these marches were a shadow of what was to come. By 1916 urban food shortages were even more critical. The war had increased demand but food production had fallen away significantly, prompting St Petersburg to authorise grain requisitioning in 31 different provinces. Some historical research suggests that Russian farmers were producing enough to feed the nation – but this food was just not reaching the cities.

“Historians sometimes contrast the February Revolution’s ‘spontaneity’ – the idea that it arose from popular protests without direct political leadership – to the ‘conspiratorial’ October Revolution, which is often described as a coup d’etat. The idea that the February Revolution occurred spontaneously also contrasts sharply with the ‘party line’ in histories published in the Soviet Union, which held that the Bolshevik Party led the masses in the February Revolution. But neither the socialist parties in the new Petrograd Soviet, nor the liberals in the Duma’s provisional committee anticipated that the February 23rd strike would snowball into revolution.”

Michael C. Hickey

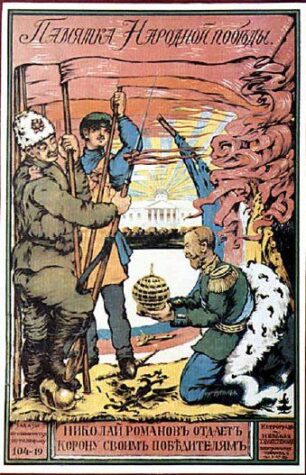

Annoyed by what he considered to be Rodzianko’s overreaction, Nicholas made one last fatal mistake: he ordered the dissolution of the Duma. This time, however, the Duma refused. Not only did it continue meeting, it also formed a provisional committee of 12 men and charged them with formulating plans for a temporary national government. On the same day (February 28th) the city’s Soviet, which first met amid the turmoil of 1905, decided to reform. Comprised mainly of Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, the Petrograd Soviet pledged to represent the interests of workers, soldiers and sailors. Russia now had two new political entities: one unelected but given delegated authority from the Duma; the other with no official authority but backed by the disgruntled working masses.

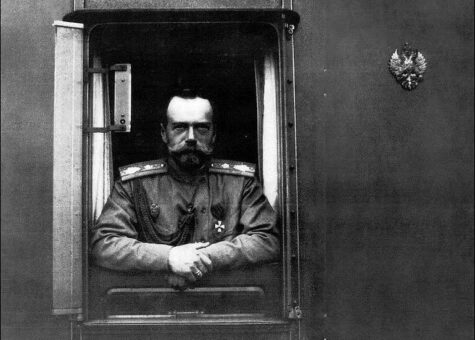

Finally succumbing to the realities of the situation, Nicholas II boarded a train back to St Petersburg – but his journey was soon stalled by breakdowns in railway infrastructure. The tsar’s train carriage was delayed on a siding at Pskov, just across the Estonian border. On March 2nd Nicholas was met in his railway car by a delegation from the Duma, which insisted on nothing less than his abdication. The tsar, still clinging to the idea that his dynasty could be saved by force, asked for time to consult his generals. But the delegation had come armed: they showed Nicholas telegrams from his generals that urged him to resign the throne. Eventually, Nicholas relented and signed the instrument of abdication, surrendering the autocratic power to Michael, his brother. Michael, however, refused to accept the crown unless an elected constituent assembly offered it to him. The throne, therefore, became empty. With the stroke of a pen, Nicholas II signed away more than 300 years of Romanov autocracy.

1. The February Revolution began as a public strike about food and fuel shortages in the Russian capital Petrograd.

2. War and domestic mismanagement had caused the transport system to fail, reducing the movement of food especially.

3. In late February food protests in Petrograd became a popular revolution, prompting the tsar to dissolve the Duma.

4. This order was ignored. The Duma instead formed a provisional committee to organise a temporary government.

5. When soldiers refused the tsar’s orders to fire on civilians, and his generals refused to back him, he eventually agreed to abdicate. The document was signed in a stranded railway car in Pskov on March 2nd 1917.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The February Revolution” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/february-revolution/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].