Enforcing Russian autocracy required both ideological and practical measures. The tsar claimed to rule by ‘divine right’, his power and authority derived from God rather than the consent of the people. In the Fundamental Laws of 1906, Russians were told to obey the tsar, “not only out of fear but also for the sake of conscience”, as he had been “ordained by God”. The Russian Orthodox Church both supported and was supported by the tsarist autocracy. The church’s governing council, the Holy Synod, was run as a de facto government department; the tsar, a deeply religious man, consulted regularly with its archbishops. The church encouraged ordinary Russians to accept and embrace autocracy; its catechisms taught worshippers that it was God’s will that they should love and obey the tsar.

Defeat in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 was disastrous for both the tsar and his government. That one of the great powers of Europe could be defeated by a small Asian nation was humiliating and evidence that improvement and modernisation were needed – not just in the ranks of the military but also the industrial sector that supplied it. Historians Nik Cornish and Andrei Karachtchouk describe this process:

It became clear that reform of the armed forces and industrialisation would have to proceed together. Domestic production of small arms and field artillery was sufficient, but for heavier artillery, communications equipment and other modern necessities it was woefully inadequate. It was necessary to import these items until Russian industry could produce what was required. The period 1910-14 saw change on a scale unprecedented during peacetime: rates of pay were increased to encourage the retention of experienced men, hundreds of officers were retired as incompetent, conscription was expanded to create a larger reserve pool, and the military budget was increased. Inevitably there was some opposition to these reforms, which polarised into hostility … consequently reform was implemented only slowly.

Tsarism was also protected and bolstered by a systematic program of censorship, counter-revolutionary espionage and police activity. The last and best-known tsarist secret police force was the Okhrana, formed in the wake of the 1881 assassination of Alexander II. The Okhrana had humble beginnings, starting as two separate secret police posts – but as the number of Marxist and anarchist groups expanded in the 1890s, so too did the number of Okhrana. By 1911 there were more than 60 security stations scattered around Russia, and even in European cities like Paris, where Russian revolutionaries-in-exile were known to be active. The assassination of Stolypin in 1911 and other internal scandals led to a winding-back of the Okhrana just prior to World War I. A significant amount of counter-revolutionary intelligence then shifted to specialist military units and branches of the gendarmes (civilian police).

“Like many other espionage agencies, the secrecy surrounding the Okhrana meant that it has been the subject of rumour, exaggeration and myth. It was frequently referred to by the totalitarian school as a prototype of the all-seeing Big Brother police system, and yet the Okhrana was a relatively small organisation, with only a few thousand employees in a country of 140 million people. It has been cited both as one of the principal causes of the revolution and as the pillar of Russian reaction. Many have presented the Okhrana as evidence of the anachronistic and backward nature of the late imperial regime, yet it was a technological and methodological innovator in the arts of political control and surveillance.”

Ian D. Thatcher, historian

At its peak in the early 1900s the Okhrana used and refined secret police methods now considered as standard. They included, but were not limited to covert surveillance, infiltration, espionage, interrogation, the use of paid informants, agent provocateurs, torture and extra-legal killing. Many Okhrana methods were adopted and embraced by later secret police units and intelligence agencies. Historian Richard Pipes points out that KGB manuals written as late as the 1970s were little more than rehashed Okhrana manuals. Among the innovations implemented by Okhrana leaders like Zubatov and Plehve were the maintenance of comprehensive files on revolutionaries and suspected dissidents, containing background information, fingerprints, aliases and photographs. Another was the forgery of provocative material, such as the anti-Semitic Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, which was created to deflect criticism of the tsar and attribute social and economic problems to Russia’s five million Jews.

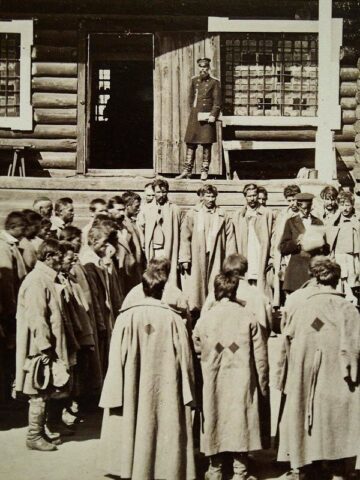

Once the Okhrana captured suspects, there were few constraints on how it could deal with them. Examination of official files after the 1917 revolution suggested the Okhrana may have been responsible for more than 26,000 extra-legal killings. Those not executed were dealt with in other ways. The more fortunate were sentenced to ssylka, a form of internal banishment where individuals were sent to live and work in remote parts of the empire. Others were sentenced to long periods in the katorga – a network of remote labour camps in Siberia, the forerunners to the gulags later operated by Stalin. Katorga inmates were forced to undertake mining, farming or construction work in appalling conditions; some were conscripted to complete ongoing work on the Trans-Siberian Railway. By the time of the Russian Revolution, the number of inmates in katorgas had dwindled to below 30,000. Among those to spend time in the katorgas were Vladimir Lenin, Bolshevik security head Felix Dzerzhinsky and the renowned novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

1. The tsar’s autocratic rule was reinforced by his claim to divine right and the teachings of the Russian Orthodox Church.

2. The military also enforced Russian autocracy by serving as a deterrent to domestic dissent or uprisings.

3. Russia had Europe’s largest peacetime army, averaging around 1.5 million men – but it was poorly equipped.

4. The Okhrana secret police also played a lead role in identifying, tracking down and dealing with political subversives.

5. The Okhrana relied on paid agents and informers, other covert methods, forced labour and extra-legal violence.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Enforcing tsarist autocracy” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/enforcing-tsarist-autocracy/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].