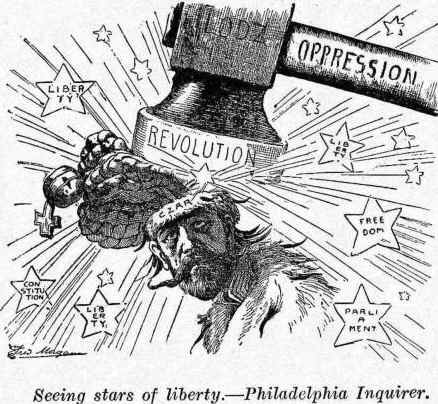

The shooting of protesting industrial workers in St Petersburg on ‘Bloody Sunday’ generated horror both in Russia and around the world. It also sparked what became known as the 1905 Revolution. Unlike some other revolutions, the 1905 Revolution was spontaneous, uncoordinated and lacked a single guiding movement or objective. Instead, it was a series of rebellious behaviours by several unconnected groups and classes, each with their own set of grievances. Though the heart of the 1905 Revolution was in the cities, which it had started, the spirit of rebellion spread across the empire to include mutinies in remote naval bases, peasant uprisings around the empire and worker unrest in Siberia. By mid-1905 the revolutionary fervour had reached such an intensity that the overthrow of tsarism seemed more likely than not. But tsarism was able to survive, in part through promises of liberal reform, in part because the revolutionary forces lacked organisation, cohesion and a common objective.

“1905 was a notable event in Trotsky’s life for other reasons, in that it offered a first opportunity of participating in an actual revolutionary situation. In 1905, he acted as a revolutionary journalist and orator, joined the St Petersburg Soviet and, briefly (for one week) became one of three co-chairmen of the Soviet’s Executive Committee. During the trial of the Soviet leaders, he made a characteristic denouncement of tsarism from the witness stand… Trotsky emerged from 1905 with a reputation of a man of action and a revolutionary of great courage and daring.”

Ian D. Thatcher, historian

Another worrying sign for tsarism was a spate of mutinies that erupted in military units through the middle and end of 1905. The most famous of these occurred aboard the battleship Potemkin on the Black Sea, triggered by officers with a liking for corporal punishment and the serving of maggot-ridden meat to mistreated sailors. In June 1905 the sailors, inspired by civilian uprisings in the cities, rebelled and killed or expelled the ship’s officers. Now in command of the Potemkin, they sailed it first to Odessa (which was under a general strike) and then to Romania, where most of them disembarked. Another mutiny broke at in November at the naval depot in Sevastopol, where several thousand sailors formed their own soviet and demanded the abolition of tsarism, a constituent assembly and improvements to their conditions.

The tsar reacted to the events of 1905 by promising reforms – but equivocating about what they should be. A day after the assassination of Sergei Alexandrovich, Nicholas declared that his ministers would investigate plans for a representative Duma (assembly). This task was largely left to the newly appointed interior minister, Alexander Bulygin, who was given the difficult task of constructing an elected Duma that did not weaken the Tsar’s autocratic power.

The Bulygin plan promised an assembly of “the most trustworthy men, having the confidence of the people and elected by them, to undertake the preliminary examination and consideration of legislative measures”. Bulygin’s memo also discussed language rights for the Poles and a reduction in the peasants’ redemption payments. But this vague proposal failed to gain support and was strongly criticised by socialists and some liberals. It also failed to assuage unrest and strikes in Russian cities.

Through all these horrible days, I constantly met Witte. We very often met in the early morning to part only in the evening when night fell. There were only two ways open; to find an energetic soldier and crush the rebellion by sheer force. That would mean rivers of blood, and in the end, we would be where we had started. The other way out would be to give to the people their civil rights, freedom of speech and press, also to have laws confirmed by a State Duma – that, of course, would be a constitution. Witte defends this very energetically. Almost everybody I had an opportunity of consulting, is of the same opinion. Witte put it quite clearly to me that he would accept the Presidency of the Council of Ministers only on the condition that his program was agreed to, and his actions not interfered with.

1. The 1905 Revolution was not a coordinated revolution but a series of anti-tsarist strikes, protests and actions.

2. Triggered by the January shootings in the capital, it began as general strikes imposed by industrial workers.

3. There was also political violence, such as the assassination of the tsar’s uncle Grand Duke Sergei.

4. Other features of the revolution were military mutinies and the formation of workers’ soviets.

5. The tsar responded by promising a representative Duma but this was not done either promptly or sincerely.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The 1905 Revolution” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/1905-revolution/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].