Cold War rivalry moved beyond the political and military spheres and into competition for technological superiority. This led to the so-called Space Race. From the mid-1950s to 1975, the United States and the Soviet Union struggled to outdo each other in rocket technology and space exploration. Both superpowers spent millions developing space-capable rockets, putting artificial satellites into orbit, designing and building orbiter ships, training astronauts, launching manned space missions and, eventually, attempting to land men on the Moon and bring them home safely. Unlike other aspects of the Cold War, the Space Race was a very public phenomenon. Every ground-breaking invention, test, launch or milestone was publicised and feted with extensive media coverage, verging on propaganda. Both the US and USSR repeatedly claimed to be ahead of the other in space exploration. In reality, their victories were fairly evenly shared over the duration of the Space Race.

The first phase of the Space Race focused on the development of rocket systems. Ironically, the early pioneers in rocket science were Germans rather than Americans or Russians. Arguably the leading rocket scientist of the early Cold War was Wernher von Braun, a former member of the Nazi Party and major in the much-hated Schutzstaffel or SS. In 1942, Braun oversaw a rocket launch that achieved sub-orbital space flight, the first man-made object to do so. An impressed Adolf Hitler ordered the manufacture of thousands of explosive-tipped rockets based on von Braun’s designs. In late 1944, more than 1,400 of these rockets – by then dubbed the V-2 – were launched at civilian targets in England. Travelling at the speed of sound, the V-2s hit their targets just three minutes after launch; their speed made them impossible to intercept with planes or anti-aircraft fire. Von Braun’s V-2s caused around 2,750 civilian deaths; one single V-2 rocket that landed on a Woolworth’s store killed 160 Londoners. Though von Braun’s innovations caused thousands of civilian deaths, both the Soviets and Americans eagerly sought his services. It was the latter who captured von Braun in the final days of World War II. By July 1945, von Braun and dozens of his staff were being shipped to the US under Operation Paperclip. These German scientists played a vital role in designing, developing and testing American rockets and missiles for the duration of the Cold War.

Despite America’s acquisition of German rocket scientists, the Soviets nevertheless made rapid advances in this field. Their expertise was put on show in October 1957, when the USSR became the first country to launch a man-made satellite into orbit. Sputnik I (the name is Russian for “traveller” or “wanderer”) was tiny in comparison to modern satellites, weighing just 90 kilograms. It circled the Earth at a speed of 28,000 kilometres per hour, orbiting once every 90 minutes. Sputnik created a sensation, the New York Times suggesting it would “go down in history…as one of the greatest achievements of man”. But Sputnik also shocked Washington, shattering assumptions that the Soviets lagged behind America in rocket and space technology. The Sputnik program also carried implied threats to US national security, since rockets that put satellites into orbit could also be used for military applications. Curtis Lemay, the United States Air Force chief, immediately prioritised research into new rocket technology.

The Space Race picked up speed during the 1950s and early 1960s. In November 1957 the Soviets launched Sputnik II, their second orbiting satellite and the first to contain a living creature, a dog named Laika. Two months later the US Army and Air Force launched their nation’s first man-made satellite, Explorer I. In July 1958 President Dwight Eisenhower ordered the formation of a dedicated space agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Within six months NASA had launched the first communications satellite, SCORE, which beamed down a message from Eisenhower. The following month (January 1959) the Soviets surged ahead again with the launch of Luna I, the first man-made satellite to leave Earth and take up orbit around the Sun. In September 1959 the Soviets also landed a probe, Luna II, on the surface of the Moon. A Soviet cosmonaut named Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space when his ship, Vostok I, completed an orbit of the Earth in April 1961. John Glenn, flying in Friendship VII, became the first American in space in February 1962. The first woman in space was Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, in June 1963. Another Soviet cosmonaut, Alexey Leonov, completed the first spacewalk in March 1965.

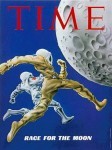

These advances were remarkable enough. The most fantastic goal of space explorers, however, was to travel beyond Earth: to the Moon or other planets. The newly elected US president John F. Kennedy sought not incremental gains in the Space Race but a surging leap ahead of the Soviets. Kennedy ordered a significant escalation in the American space program. He identified travel to and from the Moon as a long-term goal, suggesting that this could be accomplished before the end of the 1960s. In a September 1962 speech in Texas, Kennedy voiced his support for landing men on the Moon:

“But why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade, and do the other things – not because they are easy, but because they are hard. Because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills. Because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.”

The following year, Kennedy floated the possibility of a joint US-Soviet Moon mission, an idea tentatively accepted by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Unfortunately, Kennedy was assassinated weeks later so Washington and Moscow continued with their separate agendas. Through the 1960s, both countries researched and prepared for manned Moon flights. The Soviets also worked on even bolder projects, like building an orbiting space station (a feat they accomplished in 1971) and researching the possibility of manned flights to Mars and Venus. In March 1966 the Soviet space program crash-landed a probe onto the surface of Venus, the first man-made item to reach another planet. The Soviet Moon program was beset by problems and setbacks, however, and fell behind NASA’s Apollo program. In December 1968, three US astronauts onboard Apollo VIII became the first men to orbit the Moon, circling it ten times before returning safely to Earth. Then, in July the following year, two astronauts from Apollo XI, Neil Armstrong and Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin, landed safely on the Moon’s surface.

“Three domestic developments made Sputnik the enduring symbol of a crisis in American confidence: the sensationalistic response of the press, the politically motivated investigation of the ‘space and missile mess’ by Senator Lyndon Johnson, and the confused and contradictory attempts by the administration to downplay Sputnik. “I had no idea,” said President Eisenhower, “that the American people were so psychologically vulnerable.”

Walter McDougall, historian

Détente and the economic slowdown of the early 1970s affected the space program in both nations. The Space Race eventually came to a conclusion in 1975 with the launching of the Apollo-Soyuz project, the first joint US-Soviet space mission. The two powers have since collaborated on space exploration. While it often fuelled Cold War rivalry and paranoia, the Space Race also yielded considerable benefits for human society. Space exploration required and produced rapid improvements and advances in many fields, including telecommunications, micro-technology, computer science and solar power. These innovations have been utilised in a host of other applications, including consumer goods. Today, hundreds of artificial satellites orbit the Earth and provide us with international communication systems, television, global positioning systems (GPS) and weather data. Space research has also greatly enhanced our theoretical and practical understanding of astronomy, meteorology, physics and the various earth sciences.

1. The Space Race was a period of US-Soviet technical rivalry, spanning more than 25 years. During this period both superpowers competed to reach new milestones in space exploration.

2. The United States obtained a head start in the Space Race by recruiting European experts in rocket technology. Some, like Wernher von Braun, were former Nazis.

3. In October 1957 the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first man-made satellite. This development caused concern in the US, which increased its own space program.

4. The Space Race peaked in the early 1960s. During this period the Soviets put a probe on the Moon, a satellite in orbit around the Sun and the first man into space.

5. The great prize of the Space Race, however, was a successful manned landing on the Moon. This was first completed by US astronauts in July 1969. Six years later the US and USSR launched their first joint space mission, Apollo-Soyuz, which effectively ended the Space Race.

John Foster Dulles on the launching of Sputnik (1957)

A US presidential committee makes recommendations for a space program (1958)

The US National Aeronautics and Space Act (1958)

A US intelligence report on how space programs were perceived around the world (1959)

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Space Race”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/space-race/.