Transforming China into a communist society required massive social reform and restructuring of established social hierarchies. Traditional Chinese society was shaped by social structures, beliefs and practices that defined daily life. Many of these were challenged by communist ideology and forcefully reversed by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) policy and campaigns, particularly the dismantling of feudalism. Other significant CCP social reforms focused on education, religion, marriage, gender roles and family life. Mao Zedong promised that socialism would deliver equality and an egalitarian social order for all. While equality in employment, pay and marriage certainly improved, strict social controls also curbed people’s freedoms. Mass movements and campaigns were established to give the impression of democratic participation. Some of the more significant ‘democratic front’ groups included the All China Federation of Democratic Youth, the All China Federation of Trade Unions, China Democratic Federation, the All China National Women’s Federation and the Young Pioneers for children aged nine to 14. These groups were ostensibly democratic and populist – but they also acted as vehicles for social coercion and dissemination of propaganda.

One of the CCP’s first major social reforms was the Marriage Law of 1950. In theory, this law offered all citizens, particularly women, new rights, including the freedom to choose their own partner, choose their employment path and have equal ownership. Women were also liberated and empowered by the banning of old regime practices like polygamy, concubinage, child betrothal and foot binding (though this was already in decline, due largely to a ban imposed by the Dowager Empress Cixi in 1902). Divorce was legalised, though obtaining official approval remained very difficult.

The radical nature of these reforms meant they remained out of reach for many women, particularly women in rural areas that were still in the grip of patriarchal and Confucian traditions. While attitudes to marriage appeared more liberated in the new society, the CCP worked to repress social norms in regards to sex and relationships. In his book Behind the Red Door: Sex in China, Richard Burger suggests that sex and relationships were severely restricted by the CCP. Premarital sex and homosexuality were forbidden, as was prostitution, pornography, sex education – indeed any reference to sex in books or film was prohibited. According to Burger, the CCP wrapped its people “in a cocoon of chastity” and was “intent on creating a society that was basically sexless outside of their homes”.

“Prior to 1949, the [CCP] leadership had shown concern that marriage reform would undermine and complicate the class-based land reform struggles. Marriage reform issues cut across class lines and might divide class ranks. Not only did the Marriage Law raise controversy over long established moral values, but it threatened male economic positions as well: a poor male peasant might find that the gains he hoped to make through land reform would be partly or wholly cancelled out if his wife or daughter-in-law used the Marriage Law to leave his family and take her legal land share with her. No doubt many land reform authorities felt the problems of land reform were complicated enough without having to simultaneously deal with these sorts of women’s issues.”

Kay Ann Johnson, historian

In addition to marriage reform, the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (1954) also codified gender equality. Article 86 of the Constitution stated “all citizens of the People’s Republic of China, who have reached the age of 18, have the right to vote and strand for election, irrespective of their nationality, race, sex, occupation, social origin, religious belief, education, property status, or length of residence”. Article 96 declared that “women in the People’s Republic of China enjoy equal rights with men in all spheres of political, economic, cultural, social and family life”. Provisions for maternity leave and childcare made workplaces more accessible to women. The All-China Women’s Federation, formed in 1949, helped deliver some of these new freedoms to women – however historians Lily Lee and Sue Wiles argue that Chinese women were still largely excluded from the all-male party hierarchy. The political involvement of women was limited to issues pertaining to women, rather than broader policy areas. The All China Women’s Federation (formed 1949 and retitled eight years later) was more about rubber stamping government policies than developing into a politically significant body.

Social life at household and community levels was significantly disrupted by new CCP reforms. While the Agrarian Reform Law (1950) triggered significant social restructuring and delivered new freedoms and rights for China’s peasants, social life was later decimated by agricultural collectivisation, the People’s Communes and the disastrous effects of the Great Leap Forward. In addition to these changes, the hukou system of household registration was instituted in the late 1950s, in order to restrict the movement of rural and urban populations. Citizens were classified as ‘agricultural’ or ‘non-agricultural’ residents, a status that limited their place of residence and the socio-economic benefits to which they were entitled. Hukou identification was administered – and sometimes misused – by local authorities, as a means to organise resource distribution, control migration and monitor targeted groups.

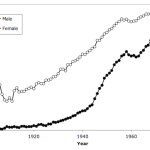

Another reform with significant social consequences was the push for improved literacy standards across China. When the communists took power, up to 85 per cent of the country was illiterate. In the old regime literacy was the domain of scholars and elites and was traditionally cultivated through the art of calligraphy. The CCP moved to simplify written characters; established the Beijing vernacular as the standard or official Chinese language; and introduced pinyin (literally, ‘spelt out sounds’) as the official system for romanising and pronouncing Chinese characters. Pinyin built on other systems, such as the older Wade Giles system, and proved effective for delivering literacy to the masses. The Committee for the Reform of the Chinese Written Language was formed in 1954 – and in 1958 the 1st National People’s Congress gave its assent to the adoption of pinyin. The pinyin system was integrated into the compulsory primary school curriculum, while thousands of illiterate adults were also taught how to read and write.

Religion was also targeted by social reformers. Confucianism and Buddhism were both in decline by 1949, however many Chinese continued to practice or at least respect elements of these faiths. Reverence for ancestors, the tending of ancestral shrines and annual religious festivals all continued in the new society. Christianity also survived through its charity work and the establishment of churches and schools. By 1949 there were still 10,000 Christian missionaries active in China. The CCP’s atheist leadership denounced all three religions, declaring them to be relics of China’s feudal past. Adherents of foreign religions were encouraged to adopt Marxism and Mao Zedong Thought as their belief system. Party cadres were more proactive in deconstructing religion, forcing the closure of churches and Christian schools and harassing and intimidating priests, nuns and missionaries.

The first decade of the People’s Republic produced antagonism between Christians and Chinese communists. Pope Pius XI had denounced communism in 1937. When his successor Pius XII was critical of the new regime in China, it increased the pressure on Christianity there. By 1951 almost all Christians had either fled or been banished from the People’s Republic. Confucianism and its fundamental beliefs about filial piety (respect for parents and ancestors) were also challenged. The family, once the cornerstone of Confucianism and Chinese society, was dramatically undermined by the reforms of the 1950s. In Mao’s China, children were considered the equal of parents. They were encouraged to be as loyal to the state as they were to their own mother or father. These changes were most noticeable during the Cultural Revolution, with hundreds of radical students and Red Guards denouncing their own parents.

1. Socialist ideals of equality and egalitarianism underpinned the social reforms implemented in China after 1949 – but they were often counterbalanced by repressive measures and social coercion.

2. Social reform was felt acutely at a household level. Social hierarchies were turned upside down, especially through the tumultuous changes instigated by the Agrarian Reform Law, collectivisation and communal living.

3. The 1950 Marriage Law and the 1954 Constitution offered women new rights and a greater sense of equality in marriage and employment. This did not necessarily result in political involvement, nor did it break down established patriarchal traditions in rural areas.

4. Literacy rates in China were greatly improved with the introduction of pinyin, a language system that made the phonetic teaching of characters much simpler, as well as other reforms.

5. The communist state was officially atheist and the major religions, including Confucianism and Christianity, were publicly denounced, undermined and attacked. Christianity was almost entirely driven out of the People’s Republic.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebecca Cairns. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Cairns, “CCP social reforms”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/ccp-social-reforms/.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.