The Proclamation of 1763 was a royal edict issued by King George III in October of that year. It prohibited the movement of persons from the 13 colonies into newly acquired western territories, in order to prevent uncontrolled settlement and dangerous encounters with Native Americans and remnant French settlers. It was a sensible policy designed to manage new territories and prevent conflict – but it was met with strong opposition from settlers and land-hungry speculators in the colonies.

Land acquisitions

Victory in the French and Indian War was met with great relief and significant optimism in the 13 colonies. For generations, the colonists had lived with the fear of French attacks and encroachment on their western borders. Many had also feared the infiltration of Catholicism practised by French settlers.

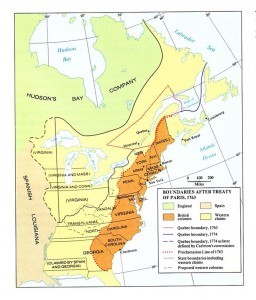

The outcomes of the war were finalised in the Treaty of Paris, signed in February 1763. Under the terms of this treaty, Britain gained large swathes of North American territory from the French. Canadian sovereignty was ceded to Britain. More significantly, London acquired almost half of French Louisiana, an area almost twice the size of the existing 13 colonies – from the Mississippi River in the west to existing colonial borders in the east, from the Great Lakes in the north to the Gulf of Mexico in the south.

These acquisitions caused great interest in the 13 colonies, exciting settlers, farmers and land speculators alike. Rapid population growth over the 1700s meant most good quality land in the 13 colonies had already been claimed. The opening of vast new lands to the west was seen as a tremendous opportunity.

The great land grab

On the western frontier, poorer elements like small freehold farmers and landless workers prepared to uproot and move westward, to lay claim on good arable land. Some had already started moving west in anticipation when the war was in its final stages.

In the cities, many affluent colonists became land speculators, hoping to snap up vast tracts in the west for resale later at profit. Land speculation companies were formed or grew in size, attracting investors and subscribers. Wealthy elites also positioned themselves to lay claims in the west.

Among these private speculators were George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, both of whom hoped to make large sums of money.

According to Ethan M. Fishman, by the time of the proclamation Washington’s landholdings had already grown to 15,000 acres “but he remained unsatiated. Washington’s quest for land was resolute, even when he knew he was not entitled to it… He declared that only a fool would bypass the chance to acquire new land.”

Pontiac’s rebellion

Another complicating factor for the British government were the Native American tribes in the western territory. Some had been allied with the French and were hostile to British rule or settlement.

These tensions increased in early 1763 following the formal peace, when British troops under General Jeffrey Amherst failed to adhere to a promise to withdraw east, instead remaining around the Great Lakes and building and maintaining fortifications.

In the spring of 1763, an Ottawa chieftain named Pontiac arranged a confederation of almost every native tribe in the region. Pontiac’s plan was to launch surprise attacks on nearby forts on a specific day, wiping out garrisons and plundering unprotected settlements. His aim was to drive the British out of the region and restore trade and relations with the French.

In May, Pontiac launched his first attack, laying siege to Fort Detroit with several hundred warriors. The fort held fast for almost six months but scores of civilians outside the fort were slaughtered. As the siege was underway, dozens of smaller forts around the Great Lakes were attacked and overrun and their garrisons butchered.

Britain responds

The British government was horrified by the attacks but understood future uprisings were likely if Native American leaders were not pacified. In October 1763, George III issued a royal proclamation pertaining to the newly acquired territories. Much of it was seen as a temporary measure until a new colonial policy could be formulated.

The proclamation was a lengthy document that outlined new government jurisdictions in Canada, Florida and the Caribbean. More specifically, it prohibited movement from the 13 colonies into the western territories, effectively drawing a border along the Appalachian Mountains and ordering that nobody settles west of this line:

“We do hereby strictly forbid, on pain of our displeasure, all our loving subjects from making any purchases or settlements whatever, or taking possession of any of the lands above reserved, without our especial leave and license for that purpose first obtained.”

Under its terms, British subjects who had claimed land west of the proclamation line – such as those already settled in the Ohio valley – were to immediately withdraw:

“We do further strictly enjoin and require all persons whatever, who have either willfully or inadvertently seated themselves upon any lands within the countries above described, or upon any other lands not having been ceded to or purchased by us… forthwith to remove themselves from such settlements.”

Colonial responses

As mentioned, one motive of the Proclamation of 1763 was to prevent further antagonism and conflict with Native American tribes. It did so by creating, in effect, a form of native title.

Under the terms of the proclamation, the western regions were reserved for the native tribes, with hunting and fishing rights granted to specific tribes according to region. Colonists were forbidden to encroach onto this land, to seize it or settle on it. Those who had already moved west were ordered to return.

Despite its sound reasoning, the Proclamation of 1763 was strongly opposed in the 13 colonies. It not only thwarted the ambitions of land speculators and settlers but disappointed veterans of the French and Indian War, some of whom had been promised land in the west for their service. The proclamation also limited colonial trade with Native Americans in the region.

The area in question was so vast, and the British military presence so negligible, that many chose to disregard the proclamation and move west anyway. An estimated 30,000 colonials crossed the line and settled in the five years that followed. Land speculators, who required the approval of grants of title, were less successful in pursuing their claims.

1. The Proclamation of 1763 was a royal decree issued by King George III to administer and regulate western territories won in the French and Indian War.

2. Britain had acquired a vast amount of land west of the Appalachians to the Mississippi River. This territory held great appeal to settlers and land speculators in the 13 colonies.

3. Facing the prospect of unrestrained settlement and potential conflicts between settlers and Native Americans, the proclamation limited movement west of the Appalachians.

4. The proclamation was intended to be a temporary measure while a better colonial policy was formulated. Nevertheless, it met strong opposition in the 13 colonies.

5. It encountered strong opposition from many in the colonies. The limited British presence and vast territory concerned encouraged many to disregard it and move west anyway.

Citation information

Title: ‘The proclamation of 1763’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/americanrevolution/proclamation-of-1763

Date published: July 15, 2019

Date updated: November 21, 2023

Date accessed: April 26, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.