Thomas Paine was a latecomer to revolutionary America. In England, Paine had failed at a number of careers, including making women’s underwear, and in 1774 it was suggested to him by Benjamin Franklin that greater opportunities might lie across the Atlantic. Taking Franklin’s advice, Paine arrived in Philadelphia in November 1774, almost dead from typhoid fever contracted during the voyage. After his recovery Paine began seeking an income through writing and printing, with negligible success.

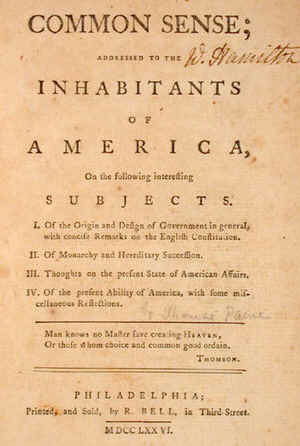

Towards the end of 1775, Paine began work on a monograph discussing the political relationship between England and America, with ongoing feedback from Benjamin Rush, a future signer of the Declaration of Independence. Rush also contributed the title, Common Sense, and the first 46-page edition was published in January 1776 – with Paine’s own money used to cover costs.

Paine suggested it was nonsensical that a continent like America should be governed by an island like England. The American colonies were not wholly or even mainly ‘English’; they were composed of peoples from all over the world. America was too economically reliant on Europe, so any European war would cause damage and suffering in America.

The distance between England and America made effective government from London an impossibility. The British parliament was supposed to be a ‘check’ on the power of the king, but the current parliament was itself corrupt. Government is inherently bad and there should be less of it, not more.

“Common Sense hit Philadelphia like a thunderclap on a calm day. It startled people. It scared some, thrilled other and enraged quite a few. The emotional impact of the pamphlet is difficult for us to appreciate, because written words no longer have such incendiary power… Yet Paine’s words encouraged [the people of America] to risk all that they held dear – their lives, livelihoods, property and those whom they loved – in a war against the world’s most formidable military power. And for what? For ephemeral concepts like freedom and equality…”

Thomas Slaughter, historian

This combination of clear reasoning and accessible language struck a chord with many colonists and thrust Paine into the spotlight as a polemicist. More than 100,000 copies of Common Sense were printed in 1776, most of them flooding around the 13 colonies as the war unfolded in Massachusetts and New York.

In a climate of dissent, rebellion and war, Paine’s writing helped to ease doubts and clarify the goal of a people in revolution.

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History 2019. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.