The Vendée is a département in western France, located south of the Loire River and on the Atlantic coastline. The Vendée was the epicentre of the largest counter-revolutionary uprising of the French Revolution and its people would pay a heavy price for their resistance. The government’s response was swift and triggered an internecine war in the region. The fight for control of the Vendée lasted three years and produced violence and mass killing that left the Parisian Terror in its wake. Sorokin suggests a conservative death toll of 58,000 but the real loss of life in the Vendée in 1793-96 may well be closer to 200,000.

Reasons for rebellion

In March 1793 provincials in the Vendée, never much interested with the revolution in Paris or its ideas, mobilised and took up arms against the National Convention. There were many reasons for this uprising but chief among them were rising land taxes, the national government’s attacks on the church, the execution of Louis XVI, the expansion of the revolutionary war and the introduction of conscription.

Viewed retrospectively, the Vendée region had all the ingredients for counter-revolutionary sentiment. Located almost 300 miles from Paris, or several days’ travel in the 1700s, it was distant and disconnected from events in the capital. The Vendée was almost entirely rural, with just a few towns and no major cities.

The vast majority of Vendeans were relatively successful peasant farmers; their living conditions were better than those of their counterparts in northern France. The Vendée peasants were not as bitterly affected by the harvest failures and bitter winter of 1788-89. They also enjoyed a comparatively better relationship with the First Estate (unlike elsewhere in France, the noblemen of the Vendée remained on their estates and did not act as absentee landlords).

The citizens of the Vendée were also devoutly religious and dependent on their local parish and clergy.

Indifference to the revolution

The attitude of Vendeans to the French Revolution can be seen in their participation, or rather lack of it, during the Great Fear. The peasants of the Vendée expressed lukewarm support for feudal reform in the cahiers but did not mobilise during the panic of July-August 1789. There were few reports of unrest in the Vendée and no chateaux were burned.

The events of 1790 further alienated the Vendeans from the revolution. Food policies determined in Paris had a detrimental impact in rural areas, where market prices slumped. Yet taxes were not lowered and in some rural areas, they actually increased.

The more pressing issue in the Vendée was the National Constituent Assembly’s attacks on the church. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy was widely resisted in the western provinces, where most of the priests refused to take the oath and were backed by their parishioners. The arrival of government officials and constitutional priests in the Vendée in 1791 and 1792 was often met with violent resistance, albeit on a small scale.

Violence breaks out

The Vendée uprising began with small steps but escalated quickly. The trigger points were the execution of Louis XVI (January 1793), then the following months’ National Convention’s Levee des 300,000 hommes, an order demanding 300,000 additional military recruits from the provinces.

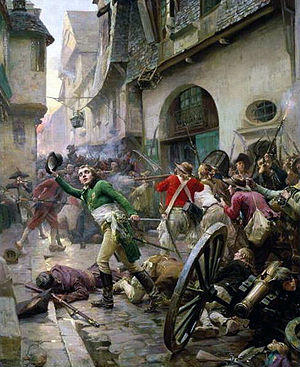

This combination of regicide and forced conscription tipped the Vendée’s peasants from localised resistance into full-scale counter-revolution. As the winter snows thawed, small bands of peasants participated in minor but provocative attacks on symbols of the republican government. Département officials, juring priests and Republican sympathisers were insulted, beaten, driven out of the region or murdered.

In mid-March, a local hawker named Jacques Cathelineau organised a group of peasants and seized weapons in Jallais. Cathelineau’s men spent the next three months clearing the region of Republican soldiers and officials.

In Beaupréau, a local peasant militia elected a former cavalry officer, Louis d’Elbée, to lead them. Under his command they captured Chemillé in April. After this victory d’Elbée prevented the slaughter of several hundred Republican prisoners by reciting the Lord’s Prayer. Another significant leader was Jean-Nicolas Stofflet, a gamekeeper and former private in the Swiss Guard, who became a general in the Vendean army.

“From March to June 1793 the movement conquered all. At the outset, the rebels were organised by villages with modest people at their head. Stofflet, an ex-soldier, was a gamekeeper; Cathelineau was a carter. But once the fighting began, the squires of the region were sought to take up the leadership. The speed of events surprised the Convention and early replies were feeble… All of a sudden the Vendée revolt broke out of its isolated bocage landscape.”

Annie Moulin, historian

Early victories

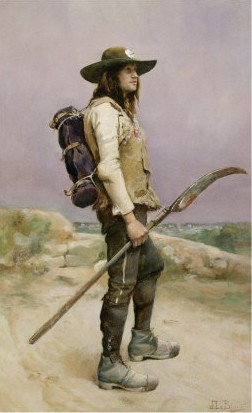

In April 1793, counter-revolutionary forces in the Vendée united to form the Catholic and Royal Army. At its peak, this army would number 80,000. Most were farmers and labourers, some were boys as young as 12 or women disguised as men.

The counter-revolutionaries adopted Dieu et Roi (‘God and King’) as their motto. Their officers wore the white cockade of the Bourbon monarchy while the soldiers wore the Sacre Couer (‘Sacred Heart’). They had little or no training and were poorly equipped, many armed with scythes and pikes rather than muskets.

While the Vendeans lacked the training and discipline to stand against a professional army, the republican armies had themselves been left weakened and disorganised by four years of disruption and desertions. For three months, the royalists of the Vendée swept all before them, capturing significant towns including Beaupréau, Vihiers, Saumur, Angers and Chemillé. They also won control of the Vendée’s most important commercial town, Cholet, and its département capital, Fontenay-le-Comte.

The National Convention had a small number of troops garrisoned in the Vendée so could do little initially.

The tide turns

The tide turned in late June 1793 when the Catholic and Royal Army marched north and laid siege to Nantes, one of France’s largest cities. Their attack was poorly planned and coordinated, and failed after just two days. Jacques Cathelineau, one of the Vendeans’ more competent commanders, was killed during fighting on Bastille Day, 1793.

In October, a 40,000-strong Vendean force marched on a smaller republican army near Cholet but was outmanoeuvred and defeated. Changing tactics, they embarked on a ‘Virée de Galerne’ (‘northern spree’), an attempt to link up with counter-revolutionaries in Brittany and Normandy. In November, the Vendeans marched on the port city of Granville, where they hoped to align with a regiment of English marines. They laid siege to Granville but found no English, only Republicans, so were forced to scatter.

Their numbers now down to fewer than 8,000 men, the Catholic and Royal Army retreated south and captured the city of Savenay. A battle-hardened Republican force of 18,000 arrived the following day and the Vendeans were soon surrounded and defeated.

Retribution

It took several months but the National Convention eventually mobilise a strong military response to the rebellion. What followed in the Vendée was a campaign of recriminations that bordered on genocide.

Under the direction of représentants en mission from Paris, Republican forces began slaughtering Vendean royalists, irrespective of their age, gender or activities. The National Convention, having already sanctioned the Reign of Terror, authorised the formation of 12 army divisions called the Colonnes Infernales (‘Infernal Columns’).

Under the command of General Louis Marie Turreau, these columns swept through the Vendée in the first half of 1794. They crisscrossed the province, tearing down buildings, burning crops and leaving death and destruction in their wake.

The instruments of the Terror were then focussed on the Vendée, where more than 6,000 people – including 400 children – were executed. Some were guillotined but most were shot, stabbed, bayoneted or forcibly drowned. Farms, crops and forests were burned across the Vendée, affecting the innocent as well as the rebels. Action against the potentially rebellious Vendée would continue as late as 1796.

1. The Vendée was a rural province in south-western France. During the spring of 1793, it became the location of the largest counter-revolutionary uprising of the French Revolution.

2. The peasants of the Vendée enjoyed better living conditions, better relations with their nobles and were less troubled by harvest failures. They were also staunch Catholics.

3. Already lukewarm towards the revolution, Vendeans responded angrily to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and other perceived attacks on the church, resisting government officials.

4. The execution of Louis XVI and the introduction of conscription tipped the Vendée into counter-revolution. By April 1793 Vendeans had formed a “Catholic and Royal Army” of 80,000 men and boys.

5. It took the Republicans several months to mobilise but by late 1793 the Vendeans had been defeated. This was followed by a long period of brutality, terror and recriminations against the Vendée that lasted for several years.

The Levee des 300,000 hommes (1793)

Reports on rebels fighting in the Vendée uprising (1793)

Benaben describes recriminations taken against rebels in the Vendée (1793)

General Turreau’s tactics in the Vendée (1794)

Citation information

Title: ‘The Vendée uprising’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/vendee-uprising/

Date published: September 20, 2019

Date updated: November 6, 2023

Date accessed: April 26, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.