Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945) was Reichsfuhrer (supreme leader) of the Schutzstaffel (SS) and the highest-ranking Nazi leader after Hitler and Hermann Goering. As the leader of the SS, Himmler was directly responsible for ordering and overseeing the detention, transportation and annihilation of the Jewish people.

Early life

Born in Munich to a family of devout Catholics, Himmler was a sickly and physically weak child and a loner, but a bright student. As a teenager, he attempted to enter the army but was rejected. Instead, he turned instead to paramilitary groups, joining an anti-Semitic group in 1922.

In the early 1920s, Himmler took a job in a manure-processing factory near Munich. During this period he came into contact with the growing Nazi Party and became a member. Himmler participated in the NSDAP’s ill-fated Munich putsch in November 1923. He later left the party for a time and worked as a chicken farmer.

In 1926, Himmler joined the SS, at the time a small but specialised division of the much larger Sturmabteilung (SA). Himmler’s fascination with discipline, control and organisation impressed Hitler, who in 1929 placed him in charge of the struggling SS. This was a fateful decision that initiated the SS’s rise to dominance.

Establishing the SS

Few in the NSDAP believed Himmler could maintain the SS, let alone manage its expansion. But despite his unimpressive, bookish appearance, Himmler was a racial fanatic who nurtured a vision of the SS as a vanguard of both racial purity and paramilitary elitism. He was determined to raise the profile of the SS and establish it as an elite army of Aryan warriors.

Himmler did this by selling the idea to Hitler. By the end of 1933, he had become one of Hitler’s most trusted advisors. With the Fuhrer’s blessing, Himmler set about reforming, rebranding and expanding the SS.

Membership was restricted to those of verifiable Aryan racial heritage. Aspiring SS officers had to demonstrate the absence of undesirable racial influences in their background by tracing their family tree back three centuries. SS officers and soldiers were also forbidden from marrying, conceiving children or having sex with non-Aryan women.

Himmler also instilled the SS with rigorous discipline and fanatical loyalty to Hitler, two attributes missing from the SA. This appealed to many ex-soldiers unhappy with the rowdiness and disorder of the SA. By late 1939, SS membership had swelled to around 512,000 men.

Himmler’s racial views

In late 1933, Himmler was given control of all concentration camps. In 1936, Hitler appointed him chief of all German police forces, including the notorious Gestapo. By this time, Himmler had found himself a willing deputy, a former naval officer named Reinhard Heydrich, a Nazi as efficient and effective as he was ruthless.

This oversight of concentration camps gave Himmler responsibility for what he later described as a difficult but necessary task: ridding Germany of its Jewish population. According to historian Christopher Hale, Himmler saw Germany as the “custodian of human culture” and his anti-Semitism was driven largely by conspiracy theories:

“Like many others, he was taken in by that faked blueprint for Jewish world conquest: ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’. Himmler added Freemasons and Jesuits to his growing list of villains, and astrology, hypnotism, spiritualism and telepathy to his enthusiasms.”

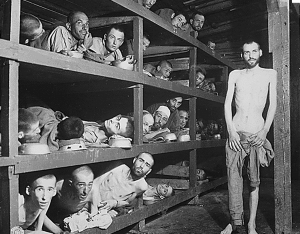

While Himmler was intensely anti-Semitic, his racism extended beyond a hatred of Jews. He considered all non-Aryan races to be untermensch (‘sub-human’) and marked for either expulsion or extermination. In a January 1937 speech, Himmler claimed “there is no more living proof of hereditary and racial laws than in a concentration camp”, full of “hydrocephalics, squinters, deformed individuals, semi-Jews; a considerable number of inferior people.” His self-declared mission was “the struggle for the extermination of any sub-humans all over the world who are in league against Germany”.

Minister of death

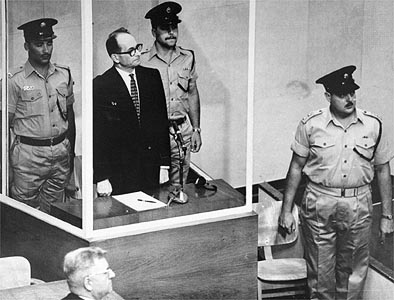

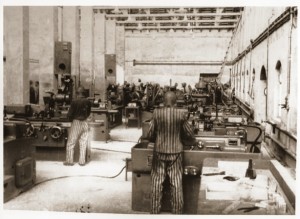

The onset of World War II gave Heinrich Himmler the opportunity to put this plan into operation. As SS Reichsfuhrer, he had overall command of the concentration camps, most labour camps, the extermination centres and the einsatzgruppen (mobile killing squadrons).

Himmler’s evils were chiefly bureaucratic: he murdered with orders and policies, his weapons the pen and telephone. It is unlikely Himmler ever killed anyone himself, in fact, one anecdotal account claims that he vomited after being sprayed with blood at an execution.

To many historians, Himmler ordered the construction of death camps and the other instruments of the Final Solution but for the most part remained distant and detached from its horrific realities. It is perhaps for this reason the deluded Himmler believed he could negotiate peace with the Allies in 1945, avoiding trial or punishment. In his own twisted mind, he had done nothing beyond what might normally be expected of a military commander in a time of war.

Complicity in the Holocaust

The weight of historical evidence lays responsibility for the Holocaust directly at Heinrich Himmler’s feet, probably more so than any other individual, including Hitler. Himmler’s awareness of the Final Solution, its motivations, objectives and methods can be found in hundreds of documents, written orders and speech transcriptions, including some pre-dating the war.

In one famous address to SS officers, given at Posen in October 1943, Himmler said:

“We have never conversed about it amongst ourselves, never spoken about it. Everyone shuddered, and everyone was clear that the next time, he would do the same thing again if it were necessary. I am talking about the ‘Jewish evacuation’: the extermination of the Jewish people. It is one of those things that is easily said. “The Jewish people is being exterminated,” every Party member will tell you. “Perfectly clear, it’s part of our plans, we’re eliminating the Jews, exterminating them. Ha! A small matter.”… But all together we can say: We have carried out this most difficult task out of love for our people. And in doing so, we have taken on no defect within us, in our soul or in our character.”

1. Heinrich Himmler was the Reichsfuhrer of the SS, putting him in charge of internal security. He was the overseer of the Final Solution and Hitler’s most loyal ally.

2. Himmler had no war or military service but his fascination with discipline, organisation and structure, as well as his intense racism and anti-Semitism, earned him favour with Hitler.

3. Himmler was given command of the SS in 1929. With Hitler’s backing, he transformed it into a highly disciplined and racially pure paramilitary group.

4. Himmler was also the Nazi Minister of the Interior, responsible for domestic security. He also had oversight over the network of Nazi concentration camps and, later, labour and death camps.

5. Historians have debated his contribution to Nazism but his role as an instigator of the Holocaust is not in dispute.

Citation information

Title: “Heinrich Himmler”

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: http://alphahistory.com/holocaust/heinrich-himmler/

Date published: August 29, 2020

Date accessed: May 17, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.