Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s reformist policies, glasnost and perestroika, had a telling effect not just on his country but the rest of the Soviet bloc. By the late 1980s, the winds of change were blowing through eastern Europe. After four decades of life in the iron grip of socialism, ordinary people in Soviet bloc nations were calling for – and often demanding – changes and freedoms. From Poland to Romania, cities in the Soviet bloc were gripped by strikes, protests and public demonstrations. Most demanded political liberalisation and economic reforms, at least on a par with those enacted in Gorbachev’s Russia. Without the backing of Moscow, the socialist governments in Soviet bloc countries had no option but to bow to public pressure. The year 1989 was particularly significant as, one by one, several former Soviet republics took the first steps to becoming free, independent and self-governing nations. For the most part, this wave of revolutions – dubbed the “Autumn of Nations” by some – took place peacefully with little or no bloodshed.

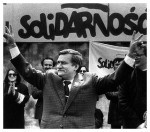

Poland was one of the first nations divided by the Cold War – and it became the first nation to shrug off communism. Poland’s was a long and protracted struggle, spanning most of the 1980s. At the heart of Polish anti-communism was a trade union called Solidarnosc (‘Solidarity’) and its plucky leader, Lech Walesa. Solidarnosc grew in popularity following years of political repression, food and goods shortages and dire working conditions. By 1981, the movement boasted more than nine million members. Poland’s communist regime responded to union-led unrest by implementing martial law and declaring Solidarnosc an illegal body; its members were thrown into prison or offered emigration to the country of their choice. In mid-1988, Polish workers began a wave of strikes. One of their conditions was the lifting of the ban on Solidarnosc, which had continued its work ‘underground’ through the 1980s. The government finally backed down in April 1989, allowing Solidarnosc to legally re-form and agreeing to hold free elections in June. Solidarnosc candidates were swept into power in this election, winning 99 percent of seats. By August 1989 Poland had a non-communist prime minister and, in December 1990, Solidarnosc leader Walesa was elected as the national president.

Hungary was the next domino to fall. In the three decades since the 1956 uprising, Hungary had taken a relatively moderate road. Hungary’s pro-Soviet leader János Kádár was brutal in his suppression of political opposition after taking power but his position moderated in the mid-1960s. Kádár maintained most socialist economic controls but sought to increase production of food and consumer goods. Some observers dubbed Kádár’s policy “goulash communism” because it combined centralised socialist economics with elements of free trade. Standards of living in Hungary improved while social controls like censorship were also eased. Kádár was replaced as leader in mid-1988, triggering a wave of public demonstrations and internal political reforms. The Hungarian government began negotiating with non-communist parties, which had re-emerged after years of banning. In May 1989 the government stunned its Soviet bloc neighbours by tearing down its border fence with Austria and allowing free movement between the two countries. Hungary’s rollback of communism was fulfilled in March 1990, with the country’s first free elections in more than 40 years.

The final months of 1989 also saw political change in Czechoslovakia. In the two decades following the famous Prague Spring of 1968, Czechoslovakia became a place where nobody dared speak against the government or socialism. Those who did were blacklisted, sacked from their jobs or expelled from school or university. The Czechoslovak state security police (StB) kept a close eye on suspected dissidents and silenced troublesome writers. But as news of Gorbachev’s glasnost rippled into Czechoslovakia, the people grew bolder in their words and actions while the Husak government became less inclined to suppress its critics. Student demonstrations in Prague in mid-November 1989 quickly grew into public rallies and labour strikes. Within two weeks the government bowed to pressure and redacted Czechoslovakia’s status as a one-party state. The Velvet Revolution, as it became known, concluded with the release from prison of liberal playwright Vaclav Havel. Havel was elected to the nation’s presidency on December 29th 1989.

A communist regime had governed Bulgaria, largely unchallenged, since 1946. Like Hungary, Bulgaria’s communists rulers permitted some economic liberalisation during the 1960s. Bulgarian farmers and manufacturers, for instance, could sell small amounts of surplus goods for profit. Bulgaria had many bars and cafes and greater emphasis on luxury items like chocolate and cigarettes; even some American goods like Coca-Cola could be purchased in Bulgarian cities. All this made Bulgaria a popular holiday destination for citizens from other Soviet bloc countries. Despite this economic diversity, the Bulgarian Communist Party ruled autocratically, suppressing dissident writers, journalists and academics. Developments elsewhere in the Soviet bloc gave rise to large public demonstrations in the Bulgarian capital Sofia in November 1989. By February 1990 the Bulgarian Communist Party had released its grip on power, leading to the nation’s first free elections four months later. Bulgaria’s first non-communist president, Zhelyu Zhelev, took power in August 1990. Zhelev had been a strident critic of Soviet socialism, likening its authoritarianism to Nazism in Germany and fascism in Italy.

The socialist republic of Romania was home to Nicolae Ceausescu, one of world’s few remaining Stalinist dictators. Ceausescu came to power in Romania in 1965 and was initially popular for his willingness to work with Western governments. He even stood up to Moscow, refusing to participate in the Soviet bloc’s 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia. In his own land, however, Ceausescu was a tyrant shielded by a deceitful cult of personality and the 80,000-strong Securitate, arguably Europe’s most brutal secret police force. In the 1980s Ceausescu’s determination to pay off Romania’s foreign debt generated massive domestic food shortages. Through 1988 and 1989, while other communist states were reforming and liberalising, Ceausescu’s Romania was becoming more oppressive and austere. By mid-December 1989, the Romanian people had tolerated enough. Tempers flared while Ceausescu was addressing a political rally in the capital Bucharest, the unrest quickly expanding into a revolution. Ceausescu and his wife attempted to flee but were arrested days later. They were given a hasty show trial and executed, bringing one of Europe’s worst Cold War dictatorships to an undignified end.

The push for democratic and liberal reforms even reached as far as communist China. Unlike in eastern Europe, however, there was no happy ending for Chinese dissidents. On April 17th 1989 around 5,000 Chinese students massed in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, calling for political change and greater accountability by the government. By mid-May, the gathering had grown into around 300,000 protestors, mainly high school and university students. At first, the communist government attempted to bargain with the protestors but to no avail. Meanwhile, numbers continued to grow as the protestors were joined in Tiananmen Square by civilians, workers, even some army personnel. Recognising the dangers, Beijing decided to act. On May 20th the government declared martial law and mobilised tanks and soldiers to clear Tiananmen Square, which by now was drastically overcrowded. By June 5th China’s military had cleared the square of protesters. As many as 2,500 people had been killed while countless others were injured or beaten. The uprising’s student leaders were hunted down, arrested and probably executed.

1. The reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union rippled through Europe, undermining socialist governments in Soviet bloc nations and prompting demands for change.

2. The earliest developments occurred in Poland, where union leader Lech Walesa and the popular movement Solidarnosc led the push for political reform.

3. Popular demonstrations led to political change elsewhere. There were liberal reforms and changes of government in Soviet bloc nations like Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria.

4. Not all communist regimes went so easily. In Romania, the authoritarian regime of Nicolae Ceausescu had to be forced from power following a revolution in December 1989.

5. The push for liberal reforms also reached China, where more than 250,000 students and civilians massed in protest in Tiananmen Square. The Chinese government reestablished control, however, by declaring martial law, sending in troops and tanks and targeting dissidents.

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The winds of change”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/winds-of-change/.