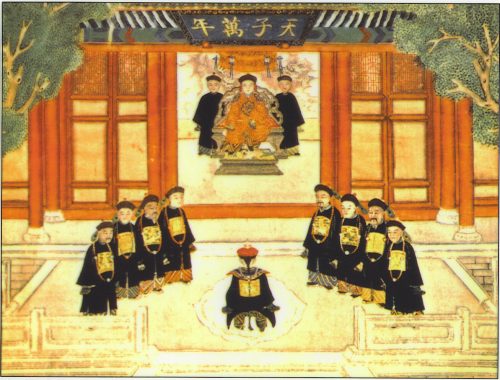

For centuries prior to the revolution, China was ruled by a number of dynasties or royal houses. Emperors from these dynasties claimed to rule the nation with a Mandate of Heaven, a form of divine approval. They also implemented and promoted Confucianism, a political and social ideology that encouraged loyalty, obedience, service and respect. These concepts and systems of thought were used to perpetuate and justify their imperial power.

China’s great dynasties

For more than 3,500 years. China was ruled by a series of dynasties or royal families, dating back to 1500BC. Each of these dynasties exerted varying levels of national power and control. Each dynasty also contributed a measure of social, cultural or religious influence on China.

One of the more influential Chinese dynasties was the Han, who reigned from the late 3rd century BC until 220AD. Han emperors implemented many changes. One of the most profound was the introduction and expansion of Confucianism, a philosophy that would permeate and shape Chinese society and government.

Another significant dynasty was the Tang (618-907AD) which made significant advances in the arts, technology and foreign trade. The Ming dynasty (1368-1644AD) has become synonymous with its cultural artefacts, especially its high-quality porcelains and works of art. Ming emperors also oversaw a growth in commerce, foreign contact and territorial expansion.

The Mandate of Heaven

These dynasties ruled through different periods of history and employed different policies and ideas. Each dynasty was bound by tianming, or the Mandate of Heaven doctrine.

The Mandate of Heaven is an Asian variation of the European ‘divine right of kings’. As in medieval Europe, ancient Egypt and other civilisations, emperors claimed their authority to rule and to govern was bestowed of them by the gods.

The Mandate of Heaven differed from the divine right of kings in three respects. Firstly, Chinese religion, unlike Christianity, was not monotheistic. The Chinese did not believe in one all-powerful god but in a number of minor gods, mythical figures, heroes and spiritual ancestors.

On that basis, the mandate to rule was granted by ‘the heavens’, a supernatural community rather than a single godhead.

Secondly, the Mandate of Heaven could be conferred on anyone, on any individual from any strata of society. The emperor did not have to be of royal or noble birth – he only had to be capable and fit to rule.

Accountability

Thirdly, and most significantly, the Mandate of Heaven held the emperor accountable to certain standards. He was answerable to Heaven and indirectly answerable to the Chinese people.

If the emperor and his government failed to govern responsibly, mistreated the people or abused their power, their authority to rule could be withdrawn. Some of the signs that Heaven had withdrawn its royal mandate included natural disasters such as floods, droughts, famines or pandemics.

Peasant rebellions were also construed as evidence that the emperor had lost the support of Heaven, as explained by Pro-ching Yip:

“As a matter of historical fact, all peasant uprisings and changes of dynasty were staged and carried out in the name of the will of heaven. It transpires that tianming means ‘destiny, i.e. orders or instructions from heaven’ and geming ‘revolution’ [both imply] the transferring of orders or instructions from heaven, taking the mandate from one ruler to give it to another. The ancient Chinese believed that intervention from heaven in terms of the heavenly mandate might take various forms. If heaven was angry, there could be floods, droughts and other natural disasters which would immediately affect the livelihood of an agricultural society. A supernatural being was believed to be behind all these doings and undoings.”

Confucius and his teachings

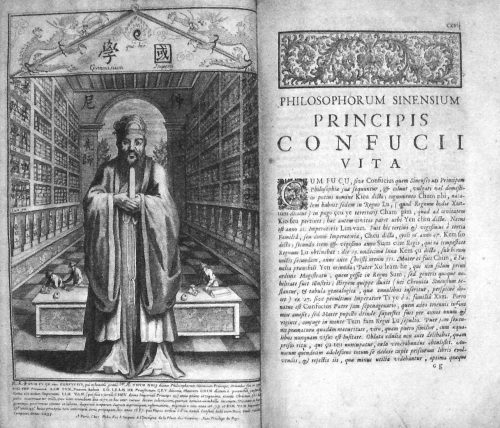

The Mandate of Heaven was reinforced by Confucianism and its teachings, a social and political philosophy derived from the writings of Chinese scholar, Kong Fuzi (Wade-Giles: Confucius) who lived between 551BC and 479BC. Most Confucian philosophy is drawn from the Analects, a compilation of Kong Fuzi’s ideas, sayings and teachings, compiled after his death.

Confucianism is sometimes considered a religion, though that is only partly true. It is also a moral and philosophical code, a guide to personal behaviour and success, and a treatise on social harmony and effective government.

Confucianism urges individuals to show respect to their elders and concern for those beneath them. Obedience, loyalty to one’s family and ancestors, dutiful service and good manners are expected at all times.

The advice given by Kong Fuzi has been stereotyped and parodied in the West as mottos that begin with “Confucius say…”. These sayings reflect Confucian concerns with wisdom, lateral thinking, good judgement and self-improvement.

Integration of Confucianism

Confucian ideas were integrated into Chinese politics and society during the Han dynasty, particularly during the long reign of Emperor Wu (ruled 141BC to 87BC).

Wu was an enthusiastic patron of Confucianism. He ordered China’s education and examination systems to incorporate the study of Confucian texts, while scholars and officials who refused to embrace Confucianism were marginalised.

In time, it became very difficult, if not impossible, for Han bureaucrats to succeed without a Confucian education. The adoption of Confucian principles in education and government saw them readily adopted by ordinary Chinese.

Emperors had an obvious agenda in their sponsorship of Confucianism, which encouraged hard work, social stability and respect for authority. But Confucianism shaped political values as much as it protected incumbent leaders. “Confucianism was not merely a passive tool of government,” wrote Xinzhong Yao, “it functioned, to a considerable extent, as a watchdog for ruling activities”.

By the 1800s, the last century of the Qing dynasty, classical Confucianism had been supplanted by neo-Confucianism, which integrated elements of Buddhist and Taoist religious philosophy. This hybrid form of Confucianism remained embedded in Chinese education and politics.

“One who managed to wrest the throne by force gained Confucian sanction for his rule. As the proverb put it bluntly: ‘He who succeeds is a king or marquis; he who fails is an outlaw’… The relative openness of the system stood in stark contrast to that of other imperial orders. In China, political challengers – be they peasants or foreign invaders – were permitted to make a bid for kingship through popular rebellion.”

Elizabeth J. Perry, historian

1. For more than 3,500 years ancient and medieval China was ruled by a number of dynasties or royal families, such as the Han, the Tang, the Ming and the Qing.

2. These dynasties claimed that their authority to rule came from a Mandate of Heaven. This was an Asian variation of the European ‘divine right of kings’.

3. Unlike in Europe, however, a royal dynasty’s Mandate of Heaven could be withdrawn if its rulers became oppressive, incompetent, neglectful or failed to govern responsibly.

4. Chinese society was also shaped by Confucianism, a philosophy based on the teachings of Kong Fuzi or Confucius. It was incorporated into China’s government, bureaucracy and education system.

5. Confucianism stressed good conduct and careful thought in all things and encouraged qualities like loyalty, obedience, self-discipline and respect for your ancestors, elders and superiors.

Citation information

Title: ‘The Mandate of Heaven and Confucianism’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Glen Kucha

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/mandate-of-heaven-confucianism/

Date published: March 11, 2019

Date updated: November 5, 2023

Date accessed: July 27, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.