The main theatre of fighting in World War I was the Western Front, a meandering line which ran from the Swiss border in the south to the North Sea. Most of the Western Front’s 700 kilometre length traversed the north-east of France, with its ends in Belgium and southern Germany. The largest battles of the war – Marne, Ypres, Verdun, the Somme, Passchendaele and others – were fought along the Western Front. Though the death toll from Western Front battles will never be accurately known, at least four million were killed there. Despite the size, frequency and ferocity of attempts to break through the line or push back the enemy, the Western Front remained relatively static until 1918. Many aspects of the Western Front have become symbolic of World War I: mud-filled trenches, artillery bombardments, appalling tactical blunders, futile charges on enemy positions, periods of stalemate, high death rates and atrocious conditions.

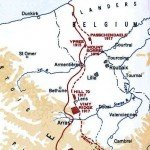

The Western Front began to take shape in the autumn of 1914, after the German advance through northern France was halted at the Battle of the Marne. The Germans then retreated to the Aisne River, where they dug a network of trenches to consolidate and hold their position. The Allies, believing the Germans were awaiting reinforcements and preparing a further assault into French territory, reciprocated by constructing their own trench system. Over the next few weeks both sides extended their trench systems further to the north, racing to outflank each other and to reach the North Sea coastline. Their aim was to prevent an enemy advance, to secure supply lines and to seize control of key ports and French industrial areas.

As the Allies and Germans carried out this ‘race to the sea’, a major battle erupted at Ypres in Belgium. At the personal order of the Kaiser, German generals launched a massive assault on the Allied line, using divisions of their most experienced infantry and cavalry – but the attack was repelled at the cost of more than 40,000 men. By the end of 1914 the Western Front trenchline had grown to more than two-thirds of its eventual length. Commanders on both sides developed grand plans to outmanoeuvre and outflank the enemy, or to break through the front. But as weeks passed, home-front enlistments pumped hundreds of thousands of reinforcements into the area. By early 1915 many parts of the Western Front were thick with soldiers on both sides of ‘no man’s land’. This weight of numbers contributed to the front’s impenetrability and the stalemate that developed through 1915. Germany’s early defeats in northern France also shaped its tactical approach. German military strategists embraced defensive positions, determined not to be forced out of France. Victory, they asserted, would pass to the side that could better withstand assaults and lose fewer men. German military planners abandoned the Schlieffen Plan and adopted a strategy of attrition, aiming to inflict death and injury on as many Allied men as possible. (The German chief of staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, famously declared that his goal was to “bleed France white”). The consequence of this was that Germany launched few major assaults in 1915; they instead relied on weapons like artillery and poison gas to weaken and debilitate Allied personnel.

“By the end of 1914, fighting on the Western Front had cost Germany 667,000 casualties, the French 995,000, the British 96,000 and the Belgians 50,000. The old professional British army had virtually ceased to exist… The Allies, who were now staging the bulk of the attacks, adopted a strategy of attrition, what General Sir Douglas Haig called ‘wearing out’ the enemy, and Joffre referred to as ‘nibbling’. This strategy, pursued by massive front assaults, resulted in hundreds of thousands of casualties. The Western Front became one great charnel house.”

Priscilla M. Roberts, historian

In contrast, British and French generals were more committed to battlefield offensives and attempts to break through the front. They tried to penetrate the German line at Champagne and Loos during the autumn of 1915, but against positions fortified with artillery and machine-guns this proved almost impossible. Falkenhayn changed tack in early 1916, hoping to lure the French army into a gigantic battle from which it could not retreat or withdraw; his aim was to inflict maximum casualties and to sap French morale. For this showdown the German commander chose the town of Verdun, near a heavily-fortified section of the Franco-German border. The Battle of Verdun, which began in February 1916, was the longest and the second-deadliest battle of World War I, claiming between 750,000 and 1,000,000 lives. It ended with no decisive victor: neither army was able to achieve their objective. Even more deadly was the Battle of the Somme, from July to November 1916. With many French generals occupied at Verdun, the Somme assault was planned and led by the British, particularly General Sir Douglas Haigh. It was to be part of a simultaneous three-way offensive: with the Russians attacking on the Eastern Front and the Italians from the south. But the choice of location, the Somme River, was problematic. German defences there sat on an elevated position; they had seen minimal action since late 1914 so had been able to construct a comprehensive system of trenches and bunkers.

The Somme assault began with an artillery barrage that lasted seven days and used more than one million shells. This assault did not wipe out or push back the Germans, who sat it out in deep bunkers; it also failed to destroy the masses of barbed wire strewn in front of German trenches. At 7.30am on July 1st 1916, more than 120,000 British soldiers leapt from their trenches and advanced on the German line. Expecting to find obliterated trenches and dead Germans, they were instead met by machine-gun fire, artillery shells, mortars and grenades. In the coming slaughter, more than 50,000 soldiers were killed in just one 24-hour period – the deadliest single day in British military history.

1. The Western Front was the main theatre of World War I, a 700-kilometre line from Switzerland to the North Sea.

2. It took shape in late 1914, as fighting in northern France stalled and both sides attempted to outflank the other.

3. Eventually the Western Front became a long line of trenches, fortifications and defences crossing western Europe.

4. Most of the major battles of the war – and therefore most of its casualties – were fought along the Western Front.

5. Breaking through the Western Front was a critical objective of military planners on both sides. These offensives were often overly ambitious, poorly planned and wasteful of men and resources.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Western Front” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/western-front/, 2014, accessed [date of last access].