The Italian front and Italy’s involvement in World War I are often overlooked – but for the Italian people, the war caused significant disruption and change. Twentieth-century Italy, like Germany, was an old culture but a new national entity. For much of the 1800s, Italy was a jigsaw of small kingdoms, duchies and city-states. A nationalist push for unification emerged in the 1820s, though in its early years it remained relatively small. European revolutions of 1848, along with the endeavours of men like Guiseppe Garibaldi and Guiseppe Mazzini, intensified the nationalist movement in the mid-19th century. The Kingdom of Italy, based in Turin, was formed in 1861. Italian independence and unification was largely completed when the new nation obtained control of Venice (1866, from Austria) and Rome (1870, from the Vatican).

In 1882, Italy became a signatory to the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. This surprised many, since for most of the 19th century the Italians and Austro-Hungarians were traditional foes. Much of this stemmed from territorial disputes. Vienna continued to occupy and claim sovereignty over the Tyrol and Trieste, areas mainly populated by Italian-speaking peoples. The Austrians had objected to, and worked to undermine, Italian unification. As a consequence, many thought hat Italy’s membership of the Triple Alliance was insincere or fragile. It allowed Italy some breathing space while she consolidated her national power and military capacity, but was unlikely to last. Some suggested that in the event of a war between the Allies and Central Powers, Rome would abandon the latter and side with the Allies.

“War objectives evoked no wide popular support in Italy, unlike in a number of other countries that joined the war with enthusiasm. Thus Italian domestic differences were not papered over at the outbreak of hostilities. On the right, the church was firmly against the war, especially one against another Catholic power, Austria. On the left, the nationalist aims of the war were derided as hollow, or as a prize to be paid for by the proletariat… Throughout the war political rifts divided the country even more bitterly.”

Francesco Galassi, historian

The outbreak of war seemed to bear out this prediction. In August 1914, the Italian government refused to commit troops to war alongside Austria-Hungary. Rome argued that the Triple Alliance’s military obligations were purely defensive, and that Vienna’s moves on Serbia constituted an act of aggression. In reality, Italian politicians were busily mulling over whether to intervene in the war – and the relative benefits of backing the Allies and the Central Powers. The majority of Italian politicians believed their nation was militarily unprepared and wanted to stay out of the war. But an influential minority – including prime minister Antonio Salandra and foreign minister Sidney Sonnino – urged intervention. Attacking traditional enemy Austria-Hungary while it was also occupied with Russia and Serbia was appealing. So too was the prospect of territorial expansion and the acquisition of new colonies. The British, recognising the Italian desire for expansion, promised Rome significant territorial rewards, to be carved from the Austro-Hungarian empire once it was defeated. Among these promises were the Tyrol, Trieste, the Austrian Littoral, parts of the Dalmatian coast, the protectorate of Albania and a share of Germany’s African and Asian colonies.

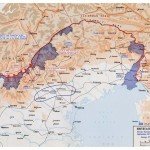

On May 3rd 1915, Italy relinquished its membership of the Triple Alliance. Twenty days later, Rome declared war on Austria-Hungary (though not on Germany) and hostilities began just days later. Between June 1915 and March 1916, Italian forces launched five separate assaults against Austrian positions in the Isonzo region. But while the Austrian defenders were heavily outnumbered, they had the advantage of elevated positions; in contrast, the Italians were led by inexperienced and overly aggressive officers who frittered away men with fruitless offensives. By the end of 1915, more than 60,000 Italians – or one-quarter of their army – had been killed. The struggle for the Isonzo continued for almost two years, with numerous counter-offensives and fallbacks. In total there were 11 different battles in the region, costing more than 130,000 Italian lives.

The stalemate in the Isonzo caused morale and support for the war to plummet. In June 1916, the failure of Italy’s military campaigns forced prime minister Salandra to resign; he was replaced by 78-year-old Paolo Boselli, a politician of no obvious talent or initiative. Pope Benedict XV was an outspoken critic of the war, calling it a “useless massacre” and a “horrible carnage that dishonours Europe”. Affected by the high death rate and the words of the Pope, Italy’s peasants shunned the war, refusing to enlist or abide by conscription orders. Desertions in the Italian army steadily increased, peaking at 60,000 in 1917. The situation worsened after the 1917 revolutions in Russia, which allowed Austro-Hungarian forces to relocate from the Eastern Front to the Italian border regions. They were joined by some German units, Rome having declared war on Berlin in August 1916.

In October 1917, some 400,000 German and Austro-Hungarian troops attacked the Italian army at Caporetto, some 60 miles north of Trieste. Despite outnumbering their attackers by more than two to one, the Italian lines were penetrated almost immediately. The Germans and Austro-Hungarians moved rapidly, outflanking and encircling much of the Italian army. When the battle had run its course by mid-November, 11,000 Italians were dead and more than a quarter-million had been taken prisoner; a great number of these surrendered voluntarily. Caporetto was an unmitigated disaster, one of the war’s worst military defeats. The government again collapsed and the prime minister and several military commanders were replaced. With the enemy now threatening Italian territory, Rome adopted more defensive military strategies. They managed to repel another much smaller Austro-Hungarian offensive in mid-1918, then counter-attacked as the Dual Monarchy crumbled in October 1918.

Italian involvement in World War I was disastrous by any measure. More than 650,000 Italian soldiers were killed, while more than one million were seriously wounded. The nation was effectively bankrupted, its national debt increasing from 15.7 billion lire (1914) to 85 billion (1919). This debt, along with economic disruption and shortages, saw inflation increase by 400 per cent. More than a half-million civilians died, most as a consequence of food shortages and poor harvests in 1918. To rub salt into these wounds, Italy did not receive everything promised to her in 1915. The Treaty of Saint-Germain (1919) gave Rome the Italian-speaking regions of Tyrol, Trieste and Istria – but sovereignty over the Dalmatian coast was granted to newly-formed Yugoslavia, while Germany’s colonies were claimed mainly by Britain and France. Many Italians believed their country had sacrificed far too much for far too little return. One of these was the fascist demagogue Benito Mussolini, who would later ride to power on the back of these nationalist sentiments.

1. Like Germany, Italy was a recently unified nation whose entry into the war was driven by nationalist ideals.

2. Italy was previously a cautious ally of Germany and Austria-Hungary, however in May 1915 she sided with the Allies.

3. Italy was lured into the war by the prospect of significant territorial gains from a defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire.

4. The Italians were militarily and economically unprepared for war, so suffered high rates of casualties and desertions.

5. The culmination of the Italian war effort was a disastrous defeat at Caporetto, which caused the government to fall and ended Italian ambitions of capturing territory from the Austro-Hungarians.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Italian Front” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/italian-front/, 2014, accessed [date of last access].