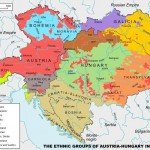

Austria-Hungary before World War I was an empire, the largest political entity in mainland Europe. It spanned almost 700,000 square kilometres and occupied much of central Europe: from the mountainous Tyrol region north of Italy, to the fertile plains of the Ukraine, to the Transylvanian mountains of eastern Europe. Eleven major ethno-language groups were scattered across the empire: Germans, Hungarians, Polish, Czech, Ukrainian, Slovak, Slovene, Croatians, Serbs, Italians and Romanians. Like Germany, the Austro-Hungarian empire was a new state comprised old peoples and cultures; it was formed in 1867 by a compromise agreement between Vienna and Budapest.

The empire’s political organisation was complex and unusual, in large part because of its origins as two separate kingdoms (it was often called the Dual Monarchy for this reason). Franz Josef was its sovereign and emperor, though he was first crowned as king both of Austria and Hungary. Each of the empire’s two monarchies continued to exist in their own right; they had their own parliament, prime ministers, cabinet and a degree of domestic self-government. As one might expect in a political union of this kind, there were grievances, dissatisfactions and frequent disagreements. The empire as a whole was overseen by a central government, responsible for matters of foreign policy, military command and joint finance. This imperial government was comprised of the emperor, both prime ministers, three appointed ministers, members of the aristocracy and representatives of the military.

At the head of the empire since its inception in 1867 was Franz Josef. In theory the emperor’s power was absolute, but Franz Josef ruled in the manner of a constitutional monarch, usually relying on the advice of his ministers. He had a difficult relationship with Franz Ferdinand, the emperor’s nephew and (from 1889) the heir to the throne. Franz Josef disliked his nephew’s liberal and progressive political views; he considered him to be wishy-washy, too easily influenced and ill-equipped for holding together the fragile Dual Monarchy. While Franz’s politics were certainly conservative, he was no warmonger and certainly nobody’s fool. He often rejected demands for strong action or the deployment of the imperial army, the interests of which he guarded jealously. Historians like Lewis Namier suggest that Franz Josef was a reluctant ruler; he was afraid of big decisions and decisive orders, in case they turned out to be wrong:

“Lonely, never sure of himself, and very seldom satisfied with his own performance he worked exceedingly hard from a compelling sense of duty, but without deriving real satisfaction from his work. Shy, sensitive and vulnerable, and apprehensive that he might cut a poor or ridiculous figure, he took refuge in a still and lifeless formalism, which made him appear wooden, and in a spiritual isolation, which made him seem unfeeling or even callous. He could not, and would not ‘improvise’: everything had to be fixed beforehand and no freedom was given to thought or to impulses.”

“Most would say that the Austro-Hungarian government decided to act as it did in 1914 because the monarchy’s ruling elite came to believe the monarchy’s interwoven external and internal problems and challenges, especially those in its South Slav regions… had become unmanageable and intolerable, calling for drastic action to change Austria-Hungary’s situation – and that the special nature, interests strongly influenced the choice of a violent rather than a peaceful solution.”

Holger Afflerbach, historian

Economically, the 19th century had been beneficial for Austro-Hungary. The empire shed its final feudal remnants and began developing and expanding capitalist institutions, such as banking, industry and manufacturing. The National Austro-Hungarian Bank was formed, supplying credit and investment funds, as well as forming a vital financial link between the two halves of the empire. Manufacturing and industrial production increased rapidly in the western half of the empire, while the east remained its agricultural heart, producing most of the Dual Monarchy’s food. Austro-Hungarian annual growth was the second-fastest in Europe, behind that of Germany. The imperial government invested heavily in railway infrastructure, chiefly because of its military benefits; by 1900 the empire had one of Europe’s best rail networks. Industrial growth and modernisation led to improvements in trade, employment and living standards.

The Dual Monarchy’s military force was essentially comprised of three armies: those which still belonged to the kingdoms of Austria and Hungary, along with a newly created force called the Imperial and Royal Army. There was considerable division between the three. The two older armies were protected by their respective parliaments, receiving more funding and better equipment and training. The imperial army was perpetually short of qualified officers, and three-quarters of those it had were Austrian. This created its own problems, since Austrian officers spoke German but the majority of soldiers were Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks and others. To combat this language gap, enlisted soldiers were taught a set of 68 single-word commands; this allowed the Imperial and Royal Army to function, though with considerable communication problems. Most soldiers were conscripts, which did not help morale. Despite these difficulties, the Austro-Hungarian imperial army was as professional as could reasonably be expected. Its high command and its officers drew on Prussian military methods, and most regiments were comparatively well-equipped with modern small arms, machine-guns and artillery.

1. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a dual monarchy, formed by a merger of the two older states in 1867.

2. Though Austrians were dominant, the empire housed many different ethnic and language groups.

3. Like Germany, went through a significant period of industrial growth and modernisation in the late 1800s.

4. Its government, led by Emperor Franz Josef, was autocratic and dominated by aristocrats and militarists.

5. Austria-Hungary had a powerful modernised army, though its was effectiveness was undermined by internal political and ethnic divisions, such as language barriers between officers and their men.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Austria-Hungary before World War I” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/austria-hungary/, 2014, accessed [date of last access].