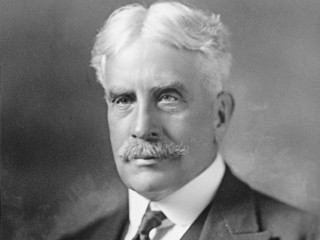

Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) was British prime minister for the first half of World War I, governing from April 1908 until his resignation in December 1916.

Born in Yorkshire and educated there and in London, Asquith won a scholarship to Oxford, studied classics and law and became a successful junior barrister. In 1886, he stood for and won the parliamentary seat of East Fife; Asquith would remain in parliament for almost 40 years, serving as home secretary, chancellor of the exchequer and, from 1908, leader of the Liberal Party and prime minister.

Asquith’s government pushed through a number of significant social and economic reforms, most notably changes to welfare. It also funded the arms race and expansion of the navy. When Germany invaded Belgium in 1914, Asquith led his government into war, despite his natural inclination being for peace.

For the first six months of the war Asquith’s popularity remained high – but falling enlistments, the lack of military progress in Europe, the failed Gallipoli campaign and the Shell Crisis of 1915 all weakened his government. In May 1915 Asquith was forced to form a coalition government with conservatives, creating divisions in the cabinet. Asquith’s personal handling of the war effort also came in for criticism, with claims that he was affected by poor health, fatigue, heavy drinking and other distractions.

The situation worsened through 1916, leading to Asquith’s resignation in December. Historians have long debated Asquith’s effectiveness as a wartime prime minister, with the majority suggesting he was too distracted and indecisive for the role.

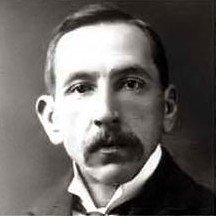

Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg (1856-1921) was a civilian politician in Germany and its chancellor (prime minister) for much of World War I. The son of a wealthy landowner, Bethmann qualified as a lawyer and joined the Prussian public service. He served as Prussia’s minister of the interior, before shifting to federal politics and becoming chancellor in 1909.

Bethmann was an intelligent but bland and uninspiring figure, more an administrator than a politician or a statesman. He did not share the militaristic or imperialist dreams of the Kaiser and his generals, nor did he support the arms and naval build up of the early 1900s. Bethmann wanted peaceful relations with Britain and Russia but in the end, his voice was lost amid the calls for war in 1914.

After August 1914, Bethmann threw himself into managing the home front. He also drafted the Septemberprogramm, a list of expansionist goals Germany hoped to fulfil after securing victory in the war. By 1917 the war had taken its toll on Germany and on Bethmann’s reputation and influence. With Germany effectively governed by the ‘Silent Dictatorship’ of Hindenburg and Ludendorff, Bethmann was reduced to a figurehead. When the Reichstag (German parliament) pushed through a resolution calling for peace negotiations in July 1917, Bethmann had no alternative but to resign the chancellorship.

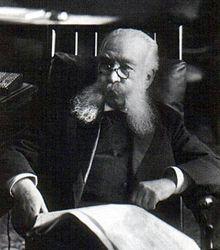

Robert Borden (1854-1937) was the prime minister of Canada from 1911 to his retirement in 1920. Born into a Nova Scotia farming family, Borden started his adult life as a teacher before becoming a successful lawyer in Halifax. He entered the Canadian parliament in 1896, by which time Borden’s legal practice and business interests had made him independently wealthy. He became the leader of Conservative Party in 1901.

Ten years later, Borden was elected as Canada’s eight prime minister since confederation. Borden threw his weight behind the war effort in 1914, reorganising the government, passing the War Measures Act and increasing the military. Borden promised that Canada would send 500,000 men to Europe by the end of 1916 – however the prolonged duration and heavy losses of the war saw enlistments decline.

Under pressure from the Allies and concerned at the lack of volunteers from French-speaking Quebec, Borden and his government passed the Military Service Act (1917), authorising the prime minister to impose conscription if deemed necessary. This controversial policy triggered riots in Quebec, and conscription itself was never fully implemented in Canada. Borden also ensured that Canadian regiments fighting in Europe retained a degree of autonomy, rather than being absorbed into the British military.

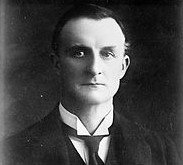

Charles de Broqueville (1860-1940) was the prime minister of Belgium for almost the entirety of World War I. From an affluent family near Moll, Broqueville was elected to the Belgian parliament before his 22nd birthday. A member of the powerful Catholic Party, Broqueville held several ministerial portfolios, before becoming party leader and prime minister in 1911.

With European tensions deteriorating, Broqueville assumed personal control of the war ministry in 1912 and ordered the expansion and modernisation of the Belgian military. His preparations were later justified by the German ultimatum and invasion in August 1914. Even as German troops occupied Belgium and its major cities, Broqueville – now in exile in France – maintained his country’s neutrality and refused to consider either an alliance with Britain and France, or a negotiated surrender with Germany.

These issues plagued his war leadership and eventually led to Broqueville’s resignation in June 1918. He remained in politics nevertheless, holding several post-war ministries and serving as prime minister again in 1932-34.

Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) was a French political leader who served two terms as the nation’s prime minister. Born in the Vendee, Clemenceau trained as a physician and worked in the United States during the 1860s. On his return to France Clemenceau joined the left wing Radical Party, entered local government in Paris and eventually took up a seat in the national legislature.

When the French government fell in 1906, Clemenceau became prime minister, a position he occupied for three years. Known for his strong speeches and barely restrained anger, Clemenceau was dubbed ‘the Tiger’ by many pundits. The outbreak of war rejuvenated Clemenceau, who had returned to journalism. He became a stringent critic of the government and its management of the war, while refusing offers of ministerial posts.

Clemenceau became prime minister again in November 1917 and immediately set about intensifying the French war effort. His personal style and authoritarian approach did not please everyone – but many welcomed Clemenceau’s strength and determination, as the British would rally behind Winston Churchill in World War II. Clemenceau made several visits to the front and worked closely with Allied commanders from all nations.

Clemenceau is perhaps best known for his actions at the Paris peace conferences in 1919, where he demanded a punitive treaty that would dismember or cripple Germany forever. He retired from politics in 1920 and returned to writing, dying nine years later.

William “Billy” Hughes (1862-1952) was an Australian politician and the nation’s prime minister from late 1915 to early 1923. Hughes was born to a working class Welsh family in England and emigrated to Australia in 1884. There he worked a series of humble jobs before becoming a union leader, a lawyer and then a member of Australia’s first federal parliament.

Hughes served three terms as the nation’s attorney general – but he was also difficult to work with and prone to stubbornness. Hughes became prime minister after the October 1915 resignation of Andrew Fisher. A strong advocate for the war effort, Hughes campaigned for an increased Australian and colonial commitment to the fighting in Europe. He visited England in 1916 and sat in on cabinet and war committee meetings. Hughes’ agitated speeches demanding stronger action proved popular with the English people, who were tiring of their dithering prime minister, Asquith.

Returning home in July 1916, Hughes sought to replace falling enlistment figures by introducing compulsory military service – but his calls for conscription were met with considerable opposition, not least from the ranks of his own party. In 1916 and 1917, Hughes initiated plebiscites (general votes) to obtain public endorsement of conscription, but the issue divided Australia and both plebiscites were defeated.

Hughes later played an important role at the Paris peace conferences. He remained prime minister until 1923 and held a seat in Australia’s parliament until his death, aged 90.

David Lloyd George (1863-1945) was a Welsh-British politician who occupied several important positions during the war, including chancellor of the exchequer, secretary of state for war and (from late 1916) prime minister.

The son of a Welsh-speaking teacher, Lloyd George was born in Manchester and raised in Wales. He trained as a lawyer, qualifying in 1884, and became involved in politics, joining the Liberal Party. Lloyd George won a seat in the British parliament in 1890 and quickly excelled as a skilled politician and a passionate public speaker. He became chancellor of the exchequer in 1908 and unfurled a range of progressive reforms, including welfare improvements funded by increased land and wealth taxes.

Initially opposed to British involvement in a European war, Lloyd George backed intervention after the German invasion of Belgium. In May 1915 he was appointed minister for munitions following the Shell Crisis and oversaw significant improvements in weapons production. Frustrated with Asquith’s lack of wartime leadership, Lloyd George played a part in his removal in December 1916. Becoming prime minister himself, Lloyd George established a five man ‘war cabinet’ and, in November 1917, a multinational Supreme War Council to coordinate Allied strategy.

Lloyd George’s war leadership was much more visible and decisive than Asquith’s but it was not without its turmoil. He clashed with his generals over military strategy, preferring to isolate and ‘starve’ Germany by attacking her allies and adopting a defensive war of attrition on the Western Front.

After the war Lloyd George was one of the ‘big three’ leaders who dominated the Paris peace talks. Historians consider him the moderate negotiator, caught between Woodrow Wilson’s idealism and Georges Clemenceau’s determination to crush Germany forever.

Ivan Goremykin (1839-1917) was chairman of the Council of Ministers (prime minister) of Russia from February 1914 until his retirement in February 1916. Like most Russian politicians, Goremykin came from a wealthy and influential land owning family. He entered the Russian bureaucracy in his early 20s and proved an effective administrator, rising through the ranks.

In 1895, Goremykin was appointed minister of the interior, holding this office for four years until his retirement. He was twice plucked from retirement, serving briefly as prime minister in 1905 then returning to this role in January 1914. Unlike prime ministers in other nations, Goremykin had almost no impact on the conduct of the war, which was overseen by the tsar and his generals. A conservative who demonstrated absolute loyalty to monarch, Goremykin accepted the tsar’s decisions and dismissed any criticism or calls for democratic reform.

When Nicholas II decided to take personal control of the army in September 1915 it was widely opposed by his ministers – except Goremykin, who supported it without question. By the end of 1915 Goremykin was in his 77th year and showing signs of dementia. He petitioned the tsar for retirement and was replaced as prime minister in February 1916. The following year, Goremykin was beaten to death by a street mob during the Russian Revolution.

Sir Edward Grey (1862-1933) was a long-serving British politician who held the office of foreign secretary during the formative years of the war. Born into a privileged family, Grey’s youthful years were listless: he was a mediocre student with uncertain career ambitions.

In 1885, Grey was elected to the House of Commons at the age of just 23. Seven years later be became an under-secretary for foreign affairs, despite having almost no experience or expertise in the field. In 1905 Grey became foreign secretary in the Asquith government, a post he held for the next 11 years.

Grey’s involvement in the outbreak of World War I has long been a topic of debate. Numerous contemporaries and historians have sharply criticised Grey for his handling of British pre-war foreign policy, and particularly the July crisis. During his tenure, British foreign policy tended to be unclear or secretive. Other than to support Belgian neutrality, Grey gave no clear indications about how Britain might respond in the event of a war on the continent. This aloofness and lack of commitment, many have argued, only encouraged German belligerence.

During the war Grey negotiated several treaties and agreements between Britain and her allies, the best known of these being the 1915 Treaty of London that brought Italy into the war. He resigned from the cabinet in December 1916, moved to the House of Lords and played little role in the wartime government thereafter.

Lord Kitchener (1850-1916) was a British general who served as minister for war until his death in June 1916. Born Herbert Kitchener in Ireland, as a teenager he followed his father into military service and saw action with the French during the Franco-Prussian War.

From the early 1880s Kitchener served almost three decades as a military commander and consul in the colonies, most notably in India, Egypt, the Sudan and South Africa. He was second in command during the Boer War and helped engineer a victory for Britain, albeit at heavy cost. When the war broke out in 1914 Kitchener, by now a field marshal, was appointed Secretary of State for War.

Unlike most of his contemporaries Kitchener expressed pessimistic but tellingly accurate views about the coming war. Rather than ‘being over by Christmas’, as some claimed, Kitchener believed it would run for years and cost millions of human lives. He also become the public face of the British war effort, appearing on a famous series of propaganda posters that indignantly insisted that British men volunteer for service.

Identifying the immovable nature of the Western Front, Kitchener supported attacks on German allies, beginning with an invasion of the Ottoman Empire; this led to Kitchener’s association with the disastrous Gallipoli campaign, which brought him some discredit. Kitchener was also subject to criticism during the Shell Crisis of mid 1915, with claims he had failed to identify the need for increased munitions production.

In June 1916 Kitchener was killed while travelling to Russia, when the Royal Navy vessel he was aboard struck a mine during a heavy storm off the Scottish coast. He was the highest ranked British military or political figure killed during World War I.

Raymond Poincare (1860-1934) was a French politician who served for eight years as the nation’s president, including the duration of World War I. Born into an affluent middle class family, the young Poincare lived through the Franco-Prussian War and the occupation of Lorraine, an event that coloured his attitude to Germans and German militarism. He went on to study and practise law before entering politics in 1886.

By his early 30s Poincare was already minister for finance and a skilled public orator. He became prime minister in January 1912 and worked to strengthen France’s alliances with both Britain and Russia. The following year Poincare was elected president of France.

Despite the presidency having been largely symbolic, Poincare used it to continue his foreign policy agenda and advance war preparations. Universal military service was increased from two years to three, while an income tax was introduced to fund arms purchases. During World War I Poincare chaired the Council of Ministers and continued to influence both domestic policy and military strategy; he also made several publicised visits to the front.

As the war took its toll on France, Poincare’s popularity also waned. In late 1917 he was forced to appoint Georges Clemenceau, a man who had often attacked Poincare in his newspapers, as prime minister. Clemenceau came to dominate both the war effort and the peace process, while Poincare took a back seat. He remained in politics, however, and returned to the prime ministership twice during the 1920s.

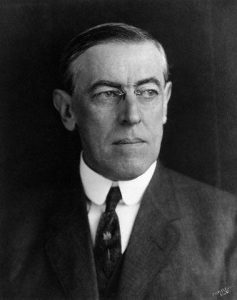

Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) was the 28th president of the United States. He held this office for the duration of World War I, oversaw America’s entry into the war and played a significant role in post-war peace negotiations.

Wilson was born in Virginia, the son of a Presbyterian minister, and as a child experienced the conflict of the American Civil War. He studied at Princeton, the University of Virginia and Johns Hopkins, qualifying as a lawyer and receiving a doctorate in history and politics. Wilson then entered academia, eventually becoming president of Princeton in 1902. In 1910 he was elected governor of New Jersey on an anti-corruption ticket, then two years later ran for the US presidency, winning comprehensively.

Wilson presented as a statesman and an isolationist opposed to war – but he was also prepared to use military force, such as his decision to land American troops in Mexico in April 1914. When war broke out in Europe in August, Wilson declared neutrality and pledged to keep America out of the conflict. He rebuffed calls to expand the US military and took a measured approach to attacks on American shipping, applying diplomatic pressure on Germany to abandon its policy of unrestricted naval warfare.

The progress of the war, along with several broken promises and the treacherous Zimmerman telegram of early 1917, convinced Wilson that American intervention was required. Reluctantly, he sought a congressional declaration of war in April 1917, declaring that “the world must be made safe for democracy”. Wilson also set about drafting a plan for post-war reconciliation and conflict resolution, to avoid future catastrophic wars.

Many of his famous Fourteen Points were later adopted at the Paris peace talks in 1919. But while Wilson’s foreign policy was successful abroad, it was not welcomed in his own country. He failed to convince Congress to ratify the Treaty of Versailles or accept membership of the League of Nations, decisions that undermined their effectiveness in Europe. Wilson suffered a significant stroke in October 1919 that left him paralysed, partially blind and able to do little work. Despite this incapacity he remained president for another 15 months, shielded by his wife, his advisors and cabinet.

© Alpha History 2018-23. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “World War I political leaders” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/world-war-i-political-leaders/, 2018, accessed [date of last access].