Bayonets

The bayonet was a comparatively simple weapon: a bracketed dagger attached to the end of a rifle barrel. Its primary function was to turn the rifle into a thrusting weapon, so its owner could attack the enemy without drawing too close. Bayonet charges were designed for psychological impact: men were trained to advance in rows, with faces contorted, lungs blaring and bayonets thrusting. Small arms and machine guns made these charges largely ineffective, but they were effective propaganda.

When not employed as weapons, bayonets were detached and used as all-purpose tools, used for anything from digging to opening canned food.

“Bayonet injuries were cruel, particularly since British soldiers were trained to ‘thrust the bayonet home then give it a sharp twist to the left, thus making the wound fatal’. Perhaps the shock-and-awe value of the bayonet is what made those 19th-century generals so enamoured of it.”

Jonathan Bastable, historian

Rifles

The rifle was standard issue for infantrymen from each country. It was relatively cheap to produce, reliable, accurate and easy to carry. British soldiers were issued with the Lee-Enfield 303, while most Germans received a 7.92mm Mauser. Both were known for their durability and long range (both could fire accurately at around 500 metres, while the Enfield could potentially kill a man two kilometres away).

This long range was largely wasted on the Western Front, where distances between trenches could be as low as 40 metres. Rifle-cleaning, maintenance and drilling occupied a good deal of an infantry soldier’s daily routine.

“The Lee-Enfield was not as effective as a semi-automatic, but with a ten-round magazine and a quick bolt action, it was far better for rapid fire than the German Kar 98K Mauser… Unfortunately British rifle training emphasised pinpoint accuracy rather than volume of fire.”

Allan Converse, historian

Pistols

In World War I, pistols or revolvers were issued mainly to officers. Enlisted soldiers only received pistols if they were required in specialist duties, such as military police work or in tank crews, where rifles would be too unwieldy.

The most famous pistol of the war was the German-made Luger, with its distinctive shape, narrow barrel and seven-shot magazine. British officers were issued with the Webley Mark IV, a reliable if somewhat ‘clunky’ weapon. The Webley could reportedly fire even when caked with mud, but it was also heavy and difficult to fire accurately. For this reason, many British officers resorted to using captured Lugers. Pistols were not usually significant on the battlefield, though they were sometimes important as concealed weapons or for close combat in the trenches.

“About 1.6 million Luger pistols of all types were made by the end of the Great War, and they earned the affection of the troops. They fired rapidly, pointed easily and were superb pistols for their time, giving excellent service if properly cared for.”

Stephen Bull, historian

Machine guns

The image of infantrymen charging pointlessly into machine gun fire is a common motif of World War I. There were fewer machine guns deployed in the war than is commonly thought – but where used they often proved deadly.

At the outbreak of war Germany had the upper hand in both the quality and quantity of machine guns. The German army had more than 10,000 units in 1914, while the British and French had fewer than 1,000 each. Machine guns of the time were capable of firing up to 500 rounds per minute – but they were cumbersome, very heavy (often more than 50 kilograms) and required at least three well trained men to set up and operate effectively. Their rapid rate of fire also caused machine guns to quickly overheat, requiring elaborate water and air-based cooling systems to prevent them from jamming or exploding.

“Few technical developments had quite the impact of the machine gun on the Western Front during the First World War. The German army’s Maxim guns effectively ended an entire, attrition-based, strategy of military campaigning, although it took the best part of the war for the allied generals to realise this.”

Peter Squires, writer

Grenades

Grenades are small bombs, thrown by hand or launched from a rifle attachment. They could be manufactured to detonate on impact or from a timing mechanism.

Germany, as it did for most other small arms, led the way in grenade development. Early British models like the Mark I (a cylindrical device attached to a long stick) were awkward to use and prone to accidental detonation. These were superseded by the pineapple-shaped Mills bomb, with its safety pin and firing lever. Mills bombs were produced with four and seven second fuses. Allied soldiers were trained to hurl Mills bombs over-arm – in fact the best cricket players were often co-opted as grenade specialists.

“The Mills bomb was a simple, rugged and effective hand grenade… At the start of the war, Britain lacked an effective grenade and troops often resorted to the use of home-made ‘jam tin’ bombs.”

Roger Lee, historian

Mortars

Essentially a 1-2 man small-calibre artillery piece, mortars launched grenades or small bombs short distances. Since most focus had been on long-range artillery, mortars had fallen out of favour with military strategists (in 1914, Germany had just 150 mortars, Britain barely any). But the development of trench warfare created an important use for mortars: they could be fired from the safety of a trench, lobbing explosives into enemy trenches from on high.

Mortars were often used to target machine-gun nests, sniper positions or smaller defensive positions. They made a distinctive ‘whoomp’ sound when launched, which was often a signal to take cover.

“The Stokes mortar… was little more than an ‘educated drain-pipe’, without wheels and divisible into man-portable loads. Its bomb was detonated by a firing pin as it fell to the bottom of the tube, and it could fire quickly enough to have three rounds in the air simultaneously.”

Hew Strachan, historian

Artillery

No development had a greater effect on the battlefields of World War I than heavy artillery. Artillery pieces were essentially huge cannons that fired explosive rounds against enemy positions, causing enormous damage to men, equipment and the landscape. During World War I they become larger, easier to handle and more accurate in their fire. They were also mobile, though moving large artillery guns became difficult if not impossible in ragged or muddy areas.

There was no denying the deadly impact of artillery: more soldiers were killed by exploding shells and shrapnel than any other weapon of the Great War. At the Battle of the Somme in 1916, almost 1.8 million shells were fired on German lines in the space of a week. The largest single artillery piece was the German-built ‘Paris gun’, used to shell the French capital from 120 kilometres away.

“Even after the appearance during World War I of machine guns, tanks and attack aircraft, artillery remained the major source of firepower on the battlefield… World War I is an example of a period in which firepower technology got far ahead of mobility technology, and the result was trench warfare.”

Spencer Tucker, historian

Tanks

Tanks are another of World War I’s legacies to modern warfare. These large armoured carriers, impervious to rifle and machine-gun fire, were initially called ‘landships’. When the first prototypes were being developed, the British military’s cover story was that they were building ‘mobile water tanks’, hence the name.

The first British tank, the Mark I, was rushed into battle at the Somme and proved susceptible to breakdown and immobility. But designers and operators soon learned from these problems, and by late 1917 the tank was proving a most useful offensive weapon, though none of them could move faster than just a few kilometres per hour.

“The effectiveness of the tank was severely curtailed, even into 1918, by the evolving nature of its technology, its limited speed and its mechanical unreliability. The British Mark V… was the first that could be controlled by one man, but carbon monoxide fumes could poison its crew.”

Hew Strachan, historian

Mines

Mines are large bombs or explosive charges, planted underground and detonated remotely or by the impact of soldiers’ feet. Navies also used sea mines, which floated on the ocean and exploded on contact with ships.

The relatively immobile warfare of the Western Front meant there was little use for anti-personnel mines – however trench soldiers often dug tunnels to plant huge mines under enemy trenches and positions. One such attack occurred at Hill 60 during the Battle of Messines (June 1917) where Australian tunnelling specialists detonated 450,000 kilograms of underground explosives, killing thousands of German troops.

“The Flanders campaign of 1917 opened June 7th. Nineteen underground mines were exploded by the British at different points in the German front line, causing panic among the German troops… A million pounds of explosives were detonated and the sound was heard in London, 130 miles away.”

Martin Gilbert, historian

Barbed wire

Barbed wire and caltrops (single iron spikes scattered on the ground) were used extensively in ‘no man’s land’ to stop enemy advances on one’s own trench. Barbed wire was laid as screens or ‘aprons’, installed by wiring parties who often worked at night. Attacking infantry often found large barbed wire screens impossible to penetrate; many died slow lingering deaths entangled in the wire.

The positioning of wire often had strategic purpose: it could keep the enemy out of grenade range from the trench, or funnel them toward machine-gun positions. More than one million kilometres of barbed wire was used on the Western Front.

“If you want to find the old battalion / I know where they are, I know where they are, I know where they are / If you want to find the old battalion, I know where they are / They’re hanging on the old barbed wire.”

British trench song

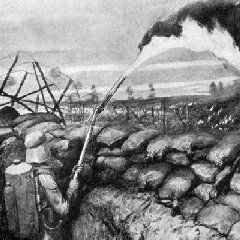

Flamethrowers

Flamethrowers, pioneered by the Germans but not widely used, were terrifying weapons. Usually wielded by an individual soldier sporting a backpack or tank, flamethrowers used pressurised gas to spurt burning oil or gasoline up to 40 metres.

The chief use of flamethrowers was as a trench-clearing weapon: the burning fuel filled trenches, landing on equipment and soldiers and forcing them to withdraw. But the comparatively short range of flamethrowers required their carriers to be within close proximity of the enemy, where they were easy pickings for a competent rifleman. The British experimented with a larger fixed-position flamethrower, using it to clear frontline trenches at the Somme.

“The psychological effects were comparable to those of gas, and that was not all the two had in common. Just as many soldiers became the victims of their own gas, the flame-thrower gave a new slant to the term ‘friendly fire’… The weapon became extremely hazardous for those using it.”

Leo van Bergen, historian

Torpedoes

Torpedoes are self-propelled missiles that can be launched from submarines or ships, or dropped into the sea from the undercarriage of planes. The first torpedoes, produced in the 1870s, ran on compressed air and were slow and inaccurate. The German navy pioneered the diesel-powered motorised torpedo. By 1914, German torpedoes could travel at up to 75 kilometres per hour over a range of several miles. This gave German U-boats a deadly advantage over Allied ships, particularly lightly armed naval vessels and unarmed civilian shipping.

As the war progressed, the British made rapid advances in torpedoes and sank at least 18 German U-boats with them.

“The Germans’ combination of submarine and torpedo technology came close to winning the First World War for the German navy in 1917. The Allies were terror-stricken by the invisible enemy. By World War I, German models weighed almost 2,500 pounds and cruised at speeds close to 40 miles per hour.”

Jason Richie, historian

© Alpha History 2019. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Weapons of World War I” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/weapons/, 2014, accessed [date of last access].