Opposition to World War I was ever-present, though it never gained sufficient numbers to challenge the perpetuation of the war. The declaration of war in August 1914 generated an upsurge of patriotism across Europe. Ordinary Europeans set aside many of their internal divisions and grievances, and rallied behind their monarchs, governments and armed forces. Enlistment offices were rushed by thousands of men, eager to ‘join up’ and play a part in what they considered an inevitable victory. Throngs of men and boys queued at recruitment fairs, eager to sign up; women and children lined the streets as their brothers, boyfriends, fathers and sons marched off to war. Newspapers like London’s Times proclaimed the great necessity for war and urged all to contribute to its succesful conduct. Yet while this confident, even euphoric mood was dominant, it was by no means universal. One British newspaper, the Manchester Guardian, wrote of the imminent declaration of war on August 1st 1914:

“War will continue to be made, until the great masses who are the sport of professional schemers and dreamers say the word [and] a determination that wars shall only be fought in a just and righteous and vital cause. If that word is ever to be spoken there never was a more appropriate occasion than the present, and we trust that it will be spoken while there is yet time. The time has come for the common sense of England to say that word now.”

All countries had anti-war movements, usually formed from disparate socialist or pacifist groups, radical unions and outspoken individuals. The main anti-war political organisation in Britain was the Independent Labour Party (ILP), a small and radical faction of the larger Labour Party. While the Labour Party was opposed to war on principle, but committed to supporting the war effort, ILP members were more stringent in their opposition. In 1914 the Labour Party had 40 Members of Parliament, of which at least six were aligned with the ILP. The war eventually created serious divisions in Labour Party ranks. Ramsay McDonald, the chairman of the Labour Party and himself an ILP member, resigned rather than give his support to a bill appropriating 100 million pounds for the war. Keir Hardie, a Scottish ILP member, spoke vehemently against the war in parliament, then tried to freeze support for it by organising a general strike in Britain and abroad. Phillip Snowdon, one of Labour’s brightest politicians, was also a bitter opponent of the war.

“The British took the lead in propaganda activities because they were forced to think seriously about such activities earlier than any of the other belligerent powers. Only in Britain was there internal disagreement about entering the conflict. Unlike major powers on the continent, Britain did not have universal conscription into the army, and thus the decision to mobilise its armed forces was more political than in France and Germany. In Britain, the Liberal Party that had been in power since 1905 was predominately anti-war, as was the opposition Labour Party, and the pressure to remain neutral in what was seen as primarily an Austro-Hungarian dispute was widespread.”

Garth S. Jowett, historian

Women’s rights groups, like Britain’s suffragette movement, also had a divided approach to the war. Many in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WPSU) were opposed, but the WPSU’s domineering leader, Christabel Pankhurst, overruled them. Pankhurst’s argument was that the fight for female equality and voting rights should be put on hold until victory had been achieved. More socialist groups, such as the East London Federation of Suffragettes, condemned the participation of British servicemen and women in the conflict. In the United States the Women’s Peace Party (WPP) was formed in January 1915, and called on neutral countries to help broker a peaceful solution. Three months later the WPP convened a three-day peace conference in the Netherlands, attended by more than 1,100 delegates from 150 countries. Their draft resolutions for peace were ignored by warring nations, though they undoubtedly shaped the peace proposals later put forward by Woodrow Wilson.

In Australia – one of the few nations where women enjoyed full voting rights – women were targeted during public campaigns about conscription. In 1916 the Australian government attempted to boost falling enlistment numbers by introducing conscription. It sought an endorsement of this move with a plebiscite (public vote), asking Australian citizens to vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ for conscription. The plebiscite unleashed a wave of public debate and propaganda for both sides of the issue. Female voters were often the target of this propaganda, which encouraged them protect their husbands and sons by voting ‘no’ to conscription – or attempted to shame them into voting ‘yes’. In the United States, a popular 1915 song called I Didn’t Raise My Boy To Be a Soldier expressed strong anti-war sentiments. Former president and pro-war advocate Theodore Roosevelt condemned this song, suggesting that any woman who was opposed to the war belonged “in China – or a harem”. (Ironically, Roosevelt’s youngest and favourite son was killed in action in France in 1918, an event that devastated him.)

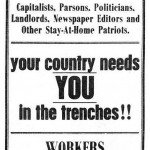

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, colloquially known as the ‘Wobblies’) was at the forefront of the anti-war movement in the United States, and to a lesser extent in Australia. An international union, the IWW was formed in America in 1906; by 1914 it had more than 10,000 members. As the chances of American involvement became more likely by late 1916, the IWW leadership became more vocal, arguing that the conflict was an ‘imperialist war’, fought to benefit land-hungry governments and profit-hungry industrialists. After the US formally entered the war in April 1917 the IWW and its members were targeted in government crackdowns, raids and arrests. Mobs occasionally enacted their own vigilante justice: in August 1917 IWW executive member Frank Little was lynched from a railroad bridge. In Australia the IWW had barely a few hundred members, yet IWW members were instrumental in forming the Anti-Conscription League which engineered the defeat of the 1916 plebiscite. The response from Australian prime minister Billy Hughes was to declare the IWW an ‘unlawful association’ and have more than a hundred of its members rounded up, arrested and sentenced to prison.

1. The initial reaction to the war was one of widespread support, fuelled by the intense nationalism of the period.

2. In Britain, political opposition to the war came from the Independent Labour Party, a faction of the larger Labour Party.

3. Some women’s rights and suffragette groups also took a leading role in trying to broker a peaceful end to the war.

4. The Australian government’s attempts to introduce conscription led to two plebiscites and strong opposition to the war.

5. The International Workers of the World (IWW) was a socialist organisation that agitated against the war, condemning it as an imperial war and calling on workers to boycott military service and participation in war industries.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Opposition to World War I” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/opposition-to-the-war/, 2014, accessed [date of last access].