The Eastern Front began with a Russian offensive against Germany in August 1914. Berlin’s Schlieffen Plan was predicated on the assumption that Russia, a gigantic country with insufficient railways and industries, would take weeks or even months to mobilise its forces. Even so, at the outbreak of war the tsar had a standing army of around 1.3 million soldiers at his disposal. Just a fortnight after the war, the tsar and his generals were planning a double-pronged offensive against the Germans and Austro-Hungarians. The first assault, they decided, would be launched against East Prussia, a German flank largely surrounded by Russian territory. Two armies, each comprised of more than 200,000 men, would be hurled against the Prussian salient from the east and south-east. The objective was to overrun East Prussia, capture its capital Konigsberg and draw German reinforcements away from Belgium and France. The Germans had anticipated this Russian offensive but not the speed at which it was organised. Berlin left the initial defence of East Prussia to ageing general Maximilian von Prittwitz and an army of 170,000 men, mostly fresh recruits from East Prussia itself.

The Russians launched their first offensive at Stalluponen on August 17th, three weeks after the declaration of war. Within days the numerically superior Russian force was moving into East Prussian territory, prompting von Prittwitz to order a mass retreat to the coast. Caught by surprise by the Russian advance, Berlin rushed reinforcements into East Prussia and replaced von Prittwitz with a more talented commander: Paul von Hindenburg. The struggle for East Prussia now hinged on talent, tactics and leadership. Hindenburg was a career soldier, highly trained and experienced at forming strategy. The two Russian armies were led by generals Alexander Samsonov and Paul von Rennenkampf. Not only were they much less experienced but each despised the other, so much that they refused to meet or even speak (a fact known to the Germans). Both were also prone to carelessness – like circulating uncoded battle plans over radio a day in advance, signals that were easily intercepted by the enemy.

Samsonov and von Rennenkampf’s inability to communicate and coordinate their armies undermined their numerical advantage. Armed with intercepted Russian battle plans, Hindenberg and his officers were able to isolate and outflank Samsonov’s army, which located to the east of Tannenberg. The Germans surrounded and bombarded them with heavy artillery for several days. Meanwhile, von Rennenkampf’s army was prevented from coming to their aid. On August 29th, General Samsonov shot himself rather than sign a humiliating surrender – but his men surrendered the following day regardless, the Germans taking almost 100,000 Russian prisoners. Ten days later, Hindenberg’s forces – now bolstered by 50,000 reinforcements – engaged von Rennenkampf’s army to the north. Now outnumbered and short of supplies, the Russians were defeated again near the Masurian Lakes. Another 45,000 Russian soldiers became German prisoners-of-war, while the rest fled back across the border. Russian soldiers would not occupy German territory again until World War II.

The defeats at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes were disastrous for Russia – but they assisted the Allied war effort by drawing German troops away from the Schlieffen offensive on the Western Front. The Russians had more battlefield success further east. In late August, the Austro-Hungarians sent a northbound invasion force into Russian-held Poland, advancing as far as Lublin. Unlike the Germans, the Austro-Hungarian army was no better trained or equipped than the Russian army. By the first week of September, St Petersburg was able to send more than 500,000 reinforcements into the area. After some of the deadliest fighting of the war, the Austro-Hungarians were soon pushed back into Galicia. The Russians eventually crossed the border but were halted by the natural defences of the Carpathian mountains. More than 120,000 Austro-Hungarians were taken prisoner, while a sizeable number defected to fight for Russia. While the Russian victory in Galicia was of marginal importance to the fighting elsewhere in Europe, it helped offset the shameful defeats at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes.

“While the Western Front experience appeared as a confrontation with modernity, the primitiveness of the East and its anachronisms sent the occupiers hurtling back through time. This sense of the primitive was heightened by the fact that in the East’s open warfare, their own advanced equipment seemed insufficient, leading to a process of ‘demodernisation’ of the Eastern Front, as technology receded in importance.”

Vejas Liulevicius, historian

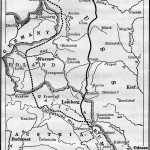

The Eastern Front took shape through 1915. By the end of the year it spanned more than 1,000 miles, running from the Baltic Sea coast near Riga, to the Ukranian shores of the Black Sea. Since it was longer, less fortified and more thinly manned than the Western Front, it was also more fluid and subject to offensives. As the stalemate on the Western Front intensified in 1915, German military commanders compensated by launching eastern offensives to drive back the Russians. The Germans and Austro-Hungarians began to coordinate their efforts, and by the end of the year they had pushed the Russians out of Poland and Galicia. The Russians attempted a massive counter-offensive in June 1916. Though it had some early successes, it eventually failed because of massive casualties, inadequate equipment and falling morale in the Russian army. The economic costs and eventual failure of the June Offensive weakened the tsarist government, which contributed to its overthrow in February 1917.

Despite the collapse of tsarism, Russia maintained its defence of the Eastern Front, which remained in place until early 1918. In October 1917 Russia was taken over by communist revolutionaries, who began negotiating a peace agreement with German generals. In March 1918 they signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ended fighting in the east. The treaty gave Russia a long-awaited peace – but it was a significant victory for Germany, which was given control of large amounts of territory in the Baltic States, Poland and the Ukraine. The three-and-a-half years of fighting on the Eastern Front claimed the lives of between three and four million men.

1. The Eastern Front saw fighting and territorial struggle between the German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian armies.

2. This front was initiated early in the war, when Russian forces attacked the German state of East Prussia.

3. By 1915 the Eastern front ran 1,000 miles, from the Baltic coast to the Black Sea, much longer than the Western Front.

4. The Eastern Front was less static: forces were more mobile and thinly spread, while trenches were used much less.

5. Fighting on the Eastern Front eventually resulted in the collapse of the tsarist government in Russia (February 1917), the Bolshevik revolution in Russia (October 1917) and Russia’s withdrawal from the war (March 1918).

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Eastern Front” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/worldwar1/eastern-front/, 2014, accessed [date of last access].