The Weimar Republic lasted less than 15 years before falling to the oncoming storm of Nazism. Countless historians have sought to understand and explain why the Weimar Republic failed. The only certainty is that the answer is complex and many factors were involved.

A myriad of problems

The Weimar Republic failed because it was at the mercy of many different ideas and forces – political and economic, internal and external, structural and short-term. It is difficult to isolate one or two of these forces or problems as being chiefly responsible for the demise of the Republic.

To the everyday observer, Adolf Hitler and Nazism appear the main architects of the downfall of Weimar democracy – but this required a collapse in the economic order, allowing Hitler and the National Socialists (NSDAP) to emerge from the margins of German politics and become a national force.

Some historians believe the Weimar Republic failed mainly because of post-war conditions in Germany. Others suggest longer-term factors, such as Germany’s inexperience with democratic forms of government, were significant. Others still point to failings in the international order, such as Germany’s brutal post-war treatment and isolation by the Allies.

This page summarises some of the main factors that contributed to the failure and fall of the Weimar state.

The Treaty of Versailles

The post-war peace settlement signed at Versailles, France in June 1919 imposed very harsh terms on the new German republic. The severity of these terms generated intense debate and political division within Germany.

While Germans overwhelmingly opposed the treaty, they were sharply divided about how to respond to it. Nationalist groups, like the NSDAP demanded the government repudiate the treaty and refuse to comply with its terms.

The moderates and pragmatists of the Weimar Republic, while also despising the treaty in principle, rejected calls for non-compliance, believing it would provoke retaliation, economic strangulation, even a resumption of the war or an Allied invasion.

Later, under the ministership of Gustav Stresemann, the Weimar government’s approach was to restore and improve foreign relations. By doing this, the government hoped for a re-negotiation of the Versailles treaty and a relaxation of its punitive terms.

Among the German people, there was a consensus that Germany had been treated unfairly by the Treaty of Versailles – and that the Weimar government had meekly obeyed the will of foreign powers.

Germany’s reparations burden

Also stemming from Versailles was the problem of reparations: the financial payments imposed on Germany for its role in initiating World War I.

Historians have formed different conclusions about reparations, whether the final reparations figure was justified and whether Germany was capable of meeting this obligation. Most agree that the reparations burden on Germany was excessive. These obligations hampered Germany’s post-war economic recovery and as a consequence undermined its political stability.

By 1922, Germany was unable to fulfil its quarterly reparations instalments, triggering the occupation of the Ruhr region by French and Belgian troops, the hyperinflation crisis of 1923 and the collapse of two Weimar government coalitions. Reparations remained a divisive issue for the duration of the Weimar Republic.

Conspiracy theories

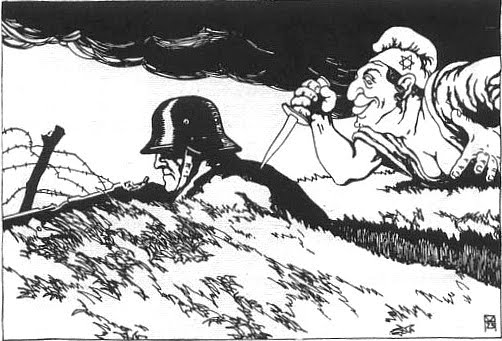

Many believe the Weimar Germany failed in part because conspiracy theories were allowed to circulate and flourish. The most prolific and poisonous was the Dolchstosselegende or ‘stab in the back’ myth. According to this fallacious theory, Germany’s surrender in November 1918 was engineered by socialists, liberals and Jews in Germany’s civilian government – it was not brought about by military defeat.

The Dolchstosselegende had three significant effects. Firstly, it undermined public trust in the civilian government and particularly the Social Democratic Party (SPD), which was painted as treacherous and unpatriotic by right-wing nationalists.

Secondly, the Dolchstosslegende perpetuated a belief that Germany could still have won the war. It implied that the German military was still strong enough to launch a counter-offensive and advance to victory. This theory is contradicted by almost all evidence on the state of the German military in late 1918.

Thirdly, the stab-in-the-back myth allowed military commanders to retain their prestige and position in German society. Despite their failures in 1918, figures like Paul von Hindenburg were able to retain their status and influence in the new republic. Evidence of this can be seen in the election of Hindenburg, who publicly supported the Dolchstosslegende, as president of the republic.

The Weimar Constitution

Germany’s post-war constitution and the political system it created must shoulder at least some of the blame for the instability of the 1920s.

The politicians who drafted the Weimar constitution attempted to construct a political system similar to that of the United States. The Weimar constitution, passed in August 1919, incorporated elements of democracy, federalism, checks and balances and protection of individual rights.

Tellingly, the constitution created an executive presidency with considerable emergency powers. The constitution allowed the president to bypass or override the elected Reichstag. Some historians suggest the Weimar president – with a seven-year term and hefty emergency powers – was not far removed from the former Kaiser.

Regular stalemates in the Reichstag meant the president’s emergency powers were frequently called into action, which only widened political divisions.

Weimar’s electoral system

The Weimar Republic’s proportional voting system was inherently democratic because it allocated Reichstag seats based on the share of votes each party received. The problem with proportional voting was that it filled the Reichstag with a large number of parties.

The first Reichstag elections in 1920 returned five parties with at least 50 seats each. There were also a host of smaller parties holding fewer than five seats and representing regional or special interests. Among these ‘micro-parties’ were the Bavarian Peasants’ League, the Agricultural League, the German Farmers Party, the Economic Party of the Middle Classes, the Reich Party for Civil Rights and the Christian Social People’s Service.

This myriad of parties and the scattered composition of the Reichstag made forming a government, passing legislation and debating issues extremely difficult.

The problems of minority government

For those reasons outlined above, no single party ever held an absolute majority of Reichstag seats during the Weimar period. This meant that no party was able to form a government on its own.

To form a government and push through legislation, parties had to group together to form a voting majority. There were several of these coalitions, or voting blocs, during the life of the Weimar Republic. The political turmoil of the 1920s meant they were fragile and unstable. A contentious bill or measure could put the coalition at risk of fracture and collapse. The fragility of these coalitions made the task of the chancellor enormously difficult.

Some parties, particularly those on the radical fringes, either refused to participate in Reichstag coalitions or entered them reluctantly or insincerely. Right-wing parties, for example, were reluctant to participate in coalitions with the large Social Democratic Party (SPD).

Germany’s defeat in World War I should have killed off or critically weakened German militarism, nationalism and faith in authoritarianism – but these powerful ideas refused to die. They survived in the post-war period and helped undermine Weimar democracy.

The main repositories for these ideas were military organisations – including the Reichswehr, the Freikorps and the various ex-soldiers’ leagues – as well as political parties on the far right, such as the NSDAP (Nazis).

Military leaders like Paul von Hindenburg, who should have been disgraced into retirement by the defeat of 1918, remained as heroes and important political players in the new society. The ‘old days of empire’ under Bismarck and the authoritarian monarchy had ended in a disastrous war – yet they were often romanticised and recalled as better times.

Hostility to democracy and parliamentarianism

Several political parties gave little or no support to the Weimar political system, instead choosing to undermine, attack or sabotage it. Parties like the Communist Party (KPD), the Nazis (NSDAP) and the German Nationalist People’s Party (DNVP) had anti-democratic platforms that sought the destruction of parliamentary democracy. These groups stood candidates in elections not to participate in the Reichstag but to damage and destroy it from within.

In the early 1930s, the NSDAP used its growing representation in the Reichstag as a platform for anti-democratic rhetoric and propaganda. Other radical parties were similarly intransigent and destructive in their approach. These attacks on Weimar democracy also contributed to the loss of public trust in the Weimar political system.

The impact of the Great Depression

Arguably the most significant reason why the Weimar Republic failed was the onset of the Great Depression. The economic collapse of 1929 had dire effects on Germany. By 1932, two-fifths of the German workforce or some six million people were without a job. This resulted in many German voters abandoning their support for mainstream and moderate parties, choosing instead to vote for radical groups.

It is unclear how much of this was genuine support for these parties and how much was a protest vote – but whatever the reasons, the NSDAP recorded significant increases in Reichstag seats in 1930 and July 1932. This propelled Adolf Hitler into the public eye, first as a presidential nominee and then as a potential chancellor.

Without the miserable conditions created by the Great Depression, Hitler and the NSDAP would likely have remained a powerless entity on the margins of Weimar politics.

Support for Hitler and the NSDAP

While Hitler and the NSDAP could not have seized power without the Great Depression, they were well placed to do so when the time came. Between 1924 and 1932, Hitler and his agents busied themselves with reforming and expanding the Nazi movement and becoming a significant political party.

They did this by presenting the NSDAP as a legitimate contender for Reichstag seats. They toned down their anti-Semitic and anti-republican rhetoric. They recruited members to increase party membership. They expanded the NSDAP from a Bavarian group into a national political party.

Hitler also chased support from powerful interest groups: German industrialists, wealthy capitalists, press barons like Alfred Hugenberg and the upper echelons of the Reichswehr. Without these tactical changes, Hitler and the NSDAP would not have been in a position to claim power in the early 1930s.

Political intriguing in 1932

The January 1933 appointment of Adolf Hitler as chancellor was the dagger through the heart of Weimar democracy. Yet just a few months before Hitler’s appointment seemed unlikely. The man whose approval was required for Hitler to become chancellor, president Paul von Hindenburg, had low regard for the NSDAP leader and no desire to appoint him as head of government.

It took weeks of intriguing, rumour-mongering and lobbying before Hindenburg, by then showing signs of senility, changed his mind. The actions of those around Hindenburg, men like former chancellor Franz von Papen, were critical factors in persuading the president that a Hitler cabinet could succeed, yet could be controlled.

Citation information

Title: “Why the Weimar Republic failed”

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/why-the-weimar-republic-failed/

Date published: October 14, 2019

Date accessed: Today’s date

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.