A decade has now passed since devolved government was restored in Northern Ireland and the unlikely duo of Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness were sworn in as First Ministers. The Good Friday Agreement has held, for the most part, and the Six Counties have enjoyed almost 20 years of relative peace. Despite this, there are lingering questions about the stability and durability of peace in Northern Ireland. While paramilitary terrorism has faded and sectarian violence is less common, Northern Ireland remains a society divided by clear political, social and religious fault lines. There have been attempts to integrate and reconcile Protestants and Loyalists with Catholics and Nationalists – yet the gulf between them remains significant. As recent events have demonstrated it does not take much – a removed flag, a disputed policy or a single act of violence – to reignite and inflame sectarian tensions. So, what next for Northern Ireland? Will peace grow and mature, washing away the old prejudices and hatreds that sparked the Troubles? Or is sectarianism and paramilitary activity only dormant and destined to recur?

Troubles tourism

A sense of hope certainly prevails in Northern Ireland, in part due to its recent economic recovery. The end of the Troubles has seen greater economic activity and investment in the Six Counties. Unemployment has tumbled to almost one-third of its level 30 years ago, though youth unemployment remains uncomfortably high. Some of this recovery has been driven by tourism. After stagnating during the Troubles, Northern Ireland’s tourism is now one of its fastest growing industries. Many international visitors are Americans, eager to visit the land of their ancestors. Others cross the border from the Republic to explore the ‘other half’ of their island. Some of Northern Ireland’s tourist attractions are internationally acclaimed. Located on the northern tip of County Antrim, the Giant’s Causeway contains thousands of black basalt columns, supported by a multi-million dollar visitor centre. In the capital, visitors flock to Titanic Belfast, an interactive centre exploring the doomed White Star liner and the slipway where she was constructed.

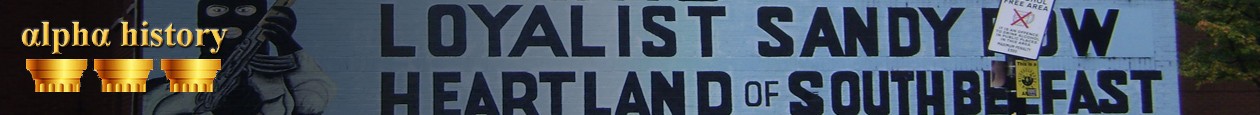

The Troubles themselves have conceived a thriving tourist trade. Beginning several years ago as a niche market, ‘Troubles tourism’ now attracts a significant number of Northern Ireland’s visitors. Many are older Britons or foreigners who followed the violence of the 1970s and 1980s in the media. Visitors interested in this turbulent period can photograph some of Northern Ireland’s colourful political murals or the peace walls separating Protestant and Catholic communities. Walking tours, black taxis and open top buses take tourists into areas once notorious for paramilitary activity and violence, such as the Shankill and Falls Roads. The Ulster Museum and the Museum of Free Derry contain hundreds of Troubles-related artefacts and images. Tourists can view the two Bloody Sunday memorials on Rossville Street; explore the memorial gardens and paramilitary tributes; or wander around the Milltown or Roselawn cemeteries, where many prominent volunteers or victims of the Troubles are buried.

Divisions maintained

Terrorist incidents and violent crime have fallen steadily since the Troubles abated in 1999. Since 2011 Northern Ireland’s homicide rate has fallen below one victim per annum per 100,000 people, a figure comparable with Britain and the Republic of Ireland. Property crime remains a concern, though it is worst in areas of unemployment and low socio-economic growth. Each year sees a handful of incidents that hark back to the Troubles. Political targets, police officers or prison guards are occasionally attacked or targeted by extremists or rogue paramilitary volunteers, usually dissident Republican groups (see below). The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) continues to monitor dangerous individuals. Several ‘lone wolf’ attacks have been thwarted by surveillance and raids. In February 2017 a former Royal Marine was arrested and charged with making bombs and planning terrorist attacks. Four months later a female Republican, Christine Connor, was jailed for 16 years for plotting to murder police officers.

Visitors to Northern Ireland will find a peaceful, orderly society – but astute observers will understand the fragility of this peace. While the Good Friday Agreement provided a political means for ending the violence, it was ambiguous about how to build a peaceful society. Most experts believe the future of peace in Northern Ireland hinges on integration (Catholics and Protestants living and working together) and reconciliation (both sides coming to terms with the past). Until then, order in Northern Ireland is maintained through segregation rather than reconciliation. Catholic and Protestant communities continue to be separated by peace walls: there are 79 of these structures in total and 17 in Belfast alone. Despite the success of integrated schools like Belfast’s Lagan College, more than 90 per cent of Northern Ireland children continue to attend segregated schools. A 2016 report by the Housing Executive noted that 90 per cent of social housing also remains segregated on religious lines.

If there is hope for the future it rests with Northern Ireland’s young people. Perhaps the best indicator of their attitudes is NI Life and Times, a nationwide survey of students aged 18 and under. Results from the 2016 poll reveal that young Northern Irelanders are acutely aware of sectarianism, segregation and the impact of religion. Their responses also suggest a measure of frustration with sectarianism, as well as signs it will away fade with newer generations. Of the young Northern Irelanders surveyed in 2016, 88 per cent said they preferred to work with people of mixed religion, while 77 per cent favoured living in mixed-religion neighbourhoods. When asked if they socialise or play sport with people from a different religion, 65 per cent said “very often” or “sometimes”.

The flag protests

Sectarian tension can still be found if one cares to look for it. It usually rears its head over issues or disputes about culture, identity or symbology. The July marching season still generates antagonism and heightens tensions across Northern Ireland. Disputes over flags have been another sticking point. In May 2011 Belfast City Council elections returned more Nationalist councillors than Unionists. In December 2012 these councillors voted to remove the British flag from atop City Hall, where it had flown daily since 1906. The Nationalists wanted the flag removed altogether but a compromise engineered by Alliance, a moderate party that held the balance of power within the council, means it will be flown on 18 special occasions each year. This ruling actually brought Belfast into line with other British councils, which followed Westminster’s guidelines on the use of the national flag.

The decision to remove the Union Jack infuriated Belfast Loyalists, who interpreted it as a Nationalist assault on their ‘Britishness’. Loyalist protestors surrounded City Hall on the day of the vote and engaged in violence after it was passed. Some protestors attempted to storm the building and 15 PSNI officers were injured. Loyalist demonstrations and violence continued across Belfast into January 2013, egged on by members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association (UDA). Much of their fury was directed at Alliance Party politicians. One Alliance MP, Naomi Long, a previous Lord Mayor of Belfast, received death threats; another Alliance politician, Linda Clelans, had her Newtownards home attacked. The flag protests continued into February 2013 before abating. The unrest and sporadic violence drew media attention and caused some damage to Northern Ireland’s tourism industry. The flag disputes persist today and still ignite heated debate between Loyalists and Nationalists.

Sleeping paramilitaries

For the Troubles to reignite, one or more paramilitary groups would have to reactivate, rearm and end the ceasefire. The status of paramilitary groups is therefore of some importance. In 2015 the British government, under pressure from Unionists, ordered an assessment of the status of Northern Ireland’s paramilitary groups. This report, handed down in October 2015, declared that major paramilitary groups were still in existence and remained a “feature of life in Northern Ireland”. Loyalist groups maintain their command structures and continue to recruit, while the Provisional IRA‘s Army Council was also in operation. The report claimed these groups were incapable of returning to their own levels of membership, firepower and operational status. “The Provisional IRA of the Troubles era”, it noted, “is well beyond recall”.

This does not mean the risk of political violence has completely evaporated. Paramilitary groups still have a capacity for violence and access to some weapons, despite the progress of decommissioning. Since 2007 numerous killings and shootings have been attributed to paramilitary volunteers. Most are attributed to internal feuds or punishment attacks on local criminals and drug dealers. While all groups have engaged in sporadic violence, only dissident Republican groups pose any serious terrorist threat. The Real IRA has continued its military campaign against the PSNI and British forces, carrying out dozens of attacks in 2010 alone. In mid-2012 the Real IRA merged with the Derry-based Republican Action Against Drugs (RAAD) and other dissident Republicans to form the New IRA. Since its formation, this new group has carried out numerous attacks and attempted attacks. In November 2012 New IRA members shot dead prison officer David Black on a freeway in County Armagh. Black’s murder, the first of a serving prison officer since 1993, shocked the public and raised fears the Troubles might be reignited. New IRA operations have continued into 2017, with gun and bomb attacks on PSNI officers.

Shifting demographics

“Two key questions will need to be answered if Northern Ireland is to move from its current uneasy stability and reluctant peace to a new phase of development characterised by cohesion and mutual respect… First, can Northern Ireland deal effectively with the enduring sectarianism that still plagues its society? [And] can Northern Ireland manage to ‘write a new history for future generations’ that is not infected by its violent past?”

Feargal Cochrane, historian

The political future of Northern Ireland may be shaped by changing demographics. Ulster’s Catholic population, with its higher birth rate and lower levels of emigration, is growing more rapidly than its Protestant population. These changes can be seen in census outcomes. In 1961, the last national census before the Troubles, 34.9 per cent of Northern Irelanders identified as Catholic. By the 2011 census, that figure had risen to 40.8 per cent. Even more revealing, in 2011 49.2 per cent of children in Northern Ireland were being raised as Catholics, compared to 36.4 per cent raised as Protestants or non-Catholics. The number of people identifying as atheists or “no religion” has also risen significantly. Catholics now form the majority of Northern Irelanders under the age of 35. If these trends continue the majority of all people in Northern Ireland will identify as Catholic by 2035.

What does this mean for Northern Ireland’s political status? This is less certain. Historically, more than 90 per cent of Catholics have voted for Nationalist or Republican political parties, such as the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) or Sinn Fein. This is no guarantee that future generations of Northern Irelanders will support a unified Ireland. Indeed, many young Catholics have shown a willingness to support the status quo. In the 2016 Life and Times poll, 66 per cent of young Northern Irelanders surveyed said they preferred to remain part of Great Britain while only 19 per cent favoured reunification with Ireland. Interestingly, a majority of Catholic respondents (44 per cent) supported retaining British sovereignty while only 35 per cent wanted to unify. Whether these views change over time or are affected by other developments, such as Great Britain’s 2016 decision to exit the European Union, remains to be seen.

1. Since the Troubles have abated, Northern Ireland has become a stable, peaceful and prosperous country, aided in part by growing levels of tourism.

2. Northern Ireland’s homicide and crime rates have fallen and are comparable to those elsewhere. Unemployment has also fallen, though youth unemployment remains high.

3. Northern Ireland’s state of peace is to a large extent based on separation. Its society remains fundamentally segregated, particularly in housing and education.

4. Paramilitary groups still exist and occasionally carry out acts of violence, however they are unlikely to regain their Troubles-era size and firepower.

5. Northern Ireland’s young people demonstrate an intolerance for sectarian views and prejudices, building hope that these attitudes will fade away with time.

An assessment of paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland (2015)

© Alpha History 2017. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole and S. Thompson, “What next for Northern Ireland?”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/what-next-for-northern-ireland/.