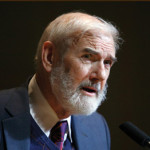

Historian: Jonathan Spence

Historian: Jonathan Spence

Lived: 1936-2021

Nationality: British-born American

Books: The Death of Woman Wang (1978), To change China: Western advisers in China 1620–1960 (1969), Mao Zedong (1990), The Gate of Heavenly Peace: The Chinese and their Revolution 1895–1980 (1982), The Chinese Century with Chin Annping (1996), Mao (1999), The Search for Modern China (2012).

Profession: Historian, academic, author, reviewer

Perspective: Unclear

Until his death in 2021, Spence was an acclaimed scholar of Chinese history, described by the Leigh Bureau as “the world’s foremost authority on Chinese civilization and the role of history in shaping modern China”. He has held professorships at Yale and visiting professorships in Beijing and Nanjing. His Chinese history course is one of the most popular undergraduate courses at Yale University.

Spence was also decorated by Queen Elizabeth II for his services to history and academia. He published prolifically on medieval and modern China. His output has been praised by both academics and general readers.

Spence’s 1982 study of the revolution, The Gates of Heavenly Peace, focused on China’s writers and intellectuals, and their fate under the communists. His 2012 book The Search for Modern China (2012) is a lengthy but unparalleled examination of 20th century China.

In historiographical terms Spence is difficult to pin down, taking a fairly balanced view and acknowledging the political, social and cultural ‘uniqueness’ of China. With regard to Mao Zedong, Spence expresses the view that Mao was a ‘Lord of Misrule’, a man of contradictions who succeeded in spite of his failures. “Mao’s beginnings were commonplace, his education episodic, his talents unexceptional,” wrote Spence, “yet he possessed a relentless energy and a ruthless self-confidence that led him to become one of the world’s most powerful rulers”.

Quotations

“Opposition to the Qing had found a new focus in the elected assemblies of local notables that had been founded in every province on orders from the court… the assembly-men soon seized new prerogatives for themselves… and began to push for the convening of a national parliament and the right to wield full legislative power.”

“Sun’s followers had infiltrated the Qing armies… the Qing government’s clumsy attempt to solve [the railway issue] by nationalising the railways became a further volatile focus for provincial anger.”

“[The rape of Nanjing] by the Japanese on December 7th 1937 brought a literal and symbolic end to any myths of Guomindang power in their own capital city.”

“Mao was not involved in the planning [of the Long March]… it was a nightmare of death and pain.”

[“[The Zunyi Conference] gave a major boost to Mao’s prestige and it is to this time that one can date his move toward a commanding position within party leadership.”

“Mao in Yan’an could hail the war with ‘enthusiasm’, partly because his base area was well insulated from the most desperate areas of fighting.”

“Mao’s completion of the Long March, and the factional battles he had fought there, had brought him a leadership position in the Party, but it was by no means unchallenged… If Mao was to become the accepted leader of his Party, he not only had to win on the battlefield and have successful policies for rural and urban revolution, he also had to be able to hold his own as a theorist.”

“As Chen Boda was thus helping Mao construct an edifice of ideological dominance, Mao was also struggling with the task of keeping Yanan a viable economic and political base.”

“Those who baulked were punished. Random violence became common, and the ‘struggles’ became deadly for many in what was euphemistically known as the ‘rescue’ campaign’, supervised by Mao’s growing teams of security personnel.”

“Totally new in all its senses and its language, it [the Constitution of the Communist Party] stated with absolute directness: ‘The Chinese Communist Party takes Mao Zedong’s thought – the thought that unites Marxist-Leninist theory and the practice of the Chinese revolution – as the guide for all its work, and opposes all dogmatic or empiricist deviations.’ Marxism was now signified: the leader was the sage.”

“Under this system [of work units] many hardworking peasants indubitable got richer, while others were pushed to the margins of subsistence.”

“This harsh counter-offensive [the Anti-Rightist campaigns] destroyed hundreds of thousands of lives.”

“Both the Hundred Flowers movement and the launching of the Great Leap show Mao more and more divorced from any true reality check… and he himself seemed to care less and less for the consequences that might spring from his own erratic utterances.”

“By 1960 famine began to strike large areas of the country. Peng Dehuai was kept out of sight, his criticism ignored… The Maoist vision had finally tumbled into nightmare.”

“Mao did not precisely orchestrate the coming of the Cultural Revolution, but he established an environment that made it possible and helped to set many of the people and issues in place.”

“The number of victims from the uncoordinated violence of the Cultural Revolution is incalculable, but there were many millions. Some of these were killed, some committed suicide. Some were crippled or scarred emotionally for life.”

“[Mao’s meting with Richard Nixon in 1972 was] an extraordinary shift in policy by Mao… and is proof of the extraordinary power that Mao knew he had over his people. But it is one of the last times we can see that power being utilised to the full.”

With the exception of material under Quotations, content on this page is © Alpha History 2018.

Content created by Alpha History may not be copied, republished or redistributed without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This website uses pinyin romanisations of Chinese words and names. Please refer to this page for more information.