At the dawn of the American Revolution, colonial society had experienced a century of growth and transformation. The fragile settlements planted by British pioneers in the early 1600s had expanded into 13 discrete, self-managing provinces occupying the eastern seaboard. Colonial economies grew and prospered, bringing rapid population growth and standards of living superior to those of most Britons. By 1763, the 13 colonies, while not without problems and inequalities, were filled with young, busy and thriving communities.

Population

It is difficult to accurately gauge population numbers in the 13 colonies because neither the British nor colonial governments conducted regular censuses until the 19th century. The consensus among historians suggests is in the 1760s, around 1.8 million people of European origin lived in British North America.

The population of the colonies had grown rapidly since their settlement in the early to mid 1600s. At the turn of the 18th century, the total population likely numbered around 250,000 people. It increased cumulatively by 30-35 per cent every decade thereafter, reaching 1 million souls sometime in the early 1740s.

By 1760, Virginia was the most populous of the 13 colonies with approximately 340,000 residents, though 40 per cent of this number were African American slaves. More than half the white European population lived in the four largest colonies: Massachusetts (220,000 people), Pennsylvania (183,000) Maryland (162,000) and Connecticut (142,000).

Historians have speculated on why colonial populations grew so rapidly over the course of a century. The lure of available land, higher wages and better opportunities in North America were undoubtedly factors. A greater abundance of food, lower population density and better living conditions also meant higher birth rates and lower infant mortality.

Demographics

Only about 58 percent of residents in the 13 colonies were of English heritage – the rest were a conglomerate of Irish, Scottish, German, Dutch and other European nationalities. These colonists shared their eastern portion of the American continent with the French to the west and north-west, and the Spanish to the south.

Living among the British colonists were approximately 500,000 slaves. Kidnapped from the west coast of Africa and sold into unpaid servitude in America, these African Americans and their descendants existed as the chattels (property) of those who purchased them to exploit their unpaid labour. On the fringes of white settlement and beyond the frontier lived tens of thousands of Native Americans, each belonging to one of almost 500 tribal groups.

One notable demographic feature of the 13 colonies was youthfulness. The immigration of younger adults, combined with high birth rates and fecundity, meant the median age in most colonies was just 16 or 17. In the New England colonies, almost one-third of the population was aged under 21. People aged over 70 were comparatively rare, as few as one or two people per hundred in some counties.

Another feature of early colonial society was a preponderance of males, a product of early emigration patterns. In the early 1700s, some regions contained only two women for every three men. There was frequent commentary about ‘women shortages’, particularly in the southern colonies, which struggled to attract female immigrants. This gender inequality dissipated over time as natural birth rates increased.

Towns and cities

Though more than 2 million Europeans and African Americans lived in the 13 colonies, most did so in small towns or isolated communities. Colonial America had few cities, and the places that considered themselves such were very small by today’s standards. America’s largest city, New York, had approximately 25,000 residents. Boston, later to become the crucible of the revolution, had somewhere in the region of 12,000.

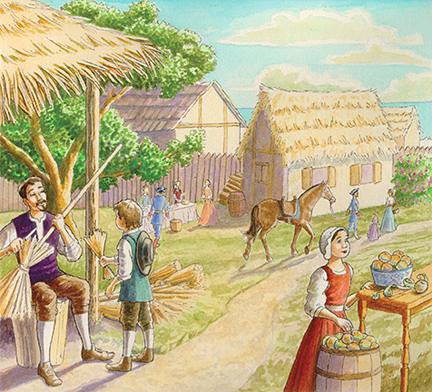

American cities were centers of trade and shipping more than industrial production. Most American colonists lived as farmers and planters, either in rural communities, small villages or on the distant frontier. Because of their isolation, these local communities became largely self-reliant and self-sufficient. Travel between American towns and villages was difficult and sometimes dangerous due to treacherous roads, unpredictable weather and the threat of hostiles.

For this reason, many Americans had not travelled more than a couple of dozen miles from their hometown. As a consequence, many communities and individuals grew to be insular, suspicious of outsiders and wary of outside interference. They feared Native American tribes, slave escapes and uprisings, the French and Spanish, travelers from other colonies – in some cases, even the city dwellers of their own colony.

Living standards

As mentioned above, living conditions in the 13 colonies were generally superior to those in Britain. Despite some early difficulties, as colonial settlements grew and acclimatised, they were able to hunt, grow or farm ample quantities of food, making malnutrition and starvation rare.

By the 1700s, colonial food production was well established. Corn, a hardy and versatile crop easily grown in a variety of conditions, became a staple grain. Depending on climate and location, it could be supplemented with wheat, rye, oats and other grains. For protein, colonists relied on domestic farm animals, hunting wild game and fishing.

In general, American colonists became better fed, more resistant to common diseases and healthier than their European counterparts. Historians have calculated that their calorific intake was significantly higher. Military records of the time suggest that American recruits were healthier, sturdier and taller than those born in Europe.

Of course, this did not make American colonists impervious to all diseases. Typhus and dysentery both took their toll on early colonial settlements. Malaria was particularly prevalent in the marshy southern colonies. Outbreaks of yellow fever, diphtheria and syphilis claimed hundreds of lives, though they tended to be localised.

“Figures on adult heights indicate an exceptionally high level of nutrition among the colonial population, especially regarding access to protein-rich red meat… Based on what is known of colonial diets, it would appear that they were fully adequate concerning calorie intake… and probably provided a balance of vitamins.”

Thomas L. Purvis, historian

Religion

Most American colonists belonged to, or at least identified with, a branch of Christianity. Religion was a significant influence in most aspects of colonial society, including its political decision-making (the separation of church and state, while often spoken of, was rarely upheld). In general, religion was a more dominant force than in Britain – particularly in conservative New England, where magistrates enforced strict rules about activities on the Sabbath.

In the 1600s, the two largest religions in the colonies were Anglicanism (the Church of England) and Congregationalism, a religious movement started by the Puritans who landed in Massachusetts in 1620. Elsewhere, one could find groups of Catholics in Maryland, Quakers in Delaware and New Jersey, as well as religiously diverse communities in Rhode Island and Pennsylvania. The colonies also had a small Jewish population and several synagogues in New York, Philadelphia and Newport.

Colonial religion underwent a significant transformation during the Great Awakening between the 1720s and 1750. It began as a response to Enlightenment ideas and declining interest in religion, sparked by Protestant leaders who worked to reform and revive spirituality in the colonies. The outcome of the Great Awakening was greater individual participation in defining and practicing religion and the growth of newer Protestant denominations, such as the Baptists and Methodists.

The Great Awakening, coupled with rapid population growth, fuelled a sharp increase in the number of churches in British North America. In 1700 there had been 374 churches, 257 of them Anglican or Congregationalist. By 1750, the tally had increased to almost 1,500 but with sharp increases in the numbers of Presbyterian (233), Lutheran (138) and Baptist (133) churches.

Women

Colonial American society was deeply patriarchal. In the first century of settlement, the role of women was limited to carrying out the duties of wife, mother, housekeeper and host. This was onerous enough, given that most household items had to be made, refined or cleaned by hand.

As the colonies evolved, some women in the more affluent classes actively participated in the work or business of their husbands. When Daniel Custis died in 1757, his wife Martha (later Martha Washington) actively took over the management and commercial operation of his tobacco plantation, then one of the largest in Virginia.

Despite sometimes playing an important role in colonial society, women enjoyed few rights. Girls and young women in wealthier families received only a restricted education focused on religion, deportment or the fine arts, such as music. Lower-class women received little or no education at all.

Adult women were not entitled to vote, hold office or sue. Property rights for women were also limited. In the case of Martha Custis, the ownership of the sizeable Virginia estate which she had inherited from her late husband and managed after her death, passed to her new husband, George Washington, after their marriage.

1. Colonial society was marked by rapid population growth, almost from its inception in the early 1600s. From 1700, it increased by around one-third every decade.

2. This was the product of high immigration rates and better standards of living. This meant that colonial society was, on average, much younger and contained a higher ratio of men.

3. Most Americans lived in smaller towns, villages or rural communities and did not travel much behind them. As a result, their interests were more local.

4. Religion was a pervasive influence in colonial society, particularly after the Great Awakening which produced a revival in religious activity and denominational changes.

5. Women enjoyed limited education and few rights, though as colonial society evolved some came to participate in the work and businesses of their husbands.

Citation information

Title: ‘Colonial society’

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/americanrevolution/colonial-society

Date published: July 15, 2019

Date updated: November 20, 2023

Date accessed: April 19, 2024

Copyright: The content on this page is © Alpha History. It may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.