Germany’s involvement in the outbreak of World War I is well documented. In the years prior to 1914, Kaiser Wilhelm II and his government adopted policies, both foreign and domestic, that contributed to rising tensions in Europe. German militarism, nationalism and imperialism – along with the Kaiser’s personal and diplomatic belligerence – all fuelled the mood for war. Every sinew of German socio-politics screamed for war. German industrialists had equipped the Kaiser’s army with a host of deadly new weapons: artillery, machine guns, chemical weapons and flamethrowers. German admirals had taken receipt of new battleships, cruisers and submarines. German strategists had drawn up ambitious war plans that promised the conquest of France in just a few weeks. Nationalists talked of expanded German imperial control and influence in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. German newspapers thundered against the bully-boy tactics being used by the ‘old empires’ of Britain and France.

In another time, the national leader might have sought to defuse this belligerent mood. But Germany’s Kaiser, Wilhelm II, was unworldly, ambitious, impatient and eager for confrontation. Where other heads of state might have said little or nothing, Wilhelm talked tough about German interests and intentions. In June 1914 Franz Ferdinand, an Austrian archduke who was heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was gunned down by Serbian radicals in the streets of Sarajevo. Rather than encouraging a measured and careful response, the German Kaiser gave the Austrians tacit approval for an invasion of Serbia. If Serbia’s allies, the Russians, became involved, the Kaiser promised to intervene. One historian later called this ‘the kaiser’s blank cheque’ for war – though it should be noted that Wilhelm’s position was supported by most German civilian politicians, even moderates in the Social Democratic Party (SPD).

When war did erupt in late July 1914, Germany initiated its famous Schlieffen Plan: a long-standing strategy to invade France via neutral Belgium, thus avoiding heavy fortifications along the French border. The plan succeeded for a time before stalling then ultimately failing. Instead of marching into France and capturing Paris within a month, Germany’s invading forces became bogged down in northern France. Defensive warfare replaced rapid advances, leading to the evolution of the Western Front – a 450-mile long network of trenches, minefields and barbed wire, running from the Swiss border to the North Sea. In the east, German forces were hurriedly mobilised to withstand a Russian advance into East Prussia. They succeeded in pushing the Russians out of German territory, though this too led to the development of another front.

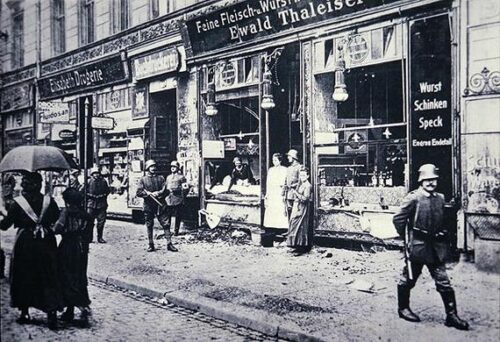

The war raged for almost four more years. By 1915 all major combatants, Germany included, had implemented a condition of ‘total war’. German military might, backed by the nation’s industrial sector, held its own on both the Western and Eastern Front. But within Germany, the civilian population became affected by isolation, blockades and shortages. Germany was not only sandwiched between enemy combatants – the Russians in the east, the British and French in the west – her coastline was also blockaded. In late 1914 the Allies took the unusual step of deeming food to be “contraband”; shipments of food headed to German ports were therefore subject to naval attack. The blockade halted German trade and imports, forcing the nation to rely on its domestic production of food. But this had also fallen significantly, due to agricultural labour being conscripted into the army or redeployed to essential wartime industries.

Geoff Layton, historian

By mid-1916, the German people were feeling the strain of two long years of total war. The civilian government, led by the ineffectual chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg, had no real answers. Meat, potatoes and dairy products became difficult to obtain, while bread was often replaced by unpleasant ersatz substitutes, made from bran or wheat husks. As both the chancellor and Reichstag dithered, the General Staff began to dictate domestic policy. This period, known by some historians as the ‘Silent Dictatorship’, saw Generals Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff assume control of civilian as well as military matters. The junta seized control of the press and propaganda, imposed food rationing and ordered compulsory labour for all civilian males of adult age. In August 1916 they introduced the Hindenburg Program, which sought to double munitions production by relocating agricultural workers into factories. Ludendorff also forced through the reintroduction of unrestricted submarine warfare against Allied ships – a policy that helped trigger the United States’ entry into the war.

In July 1917 the Reichstag, hitherto supportive of the war effort, responded to the deteriorating situation by passing a resolution calling for peace. This forced the resignation of chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg; he was replaced by unimportant men who served as puppets for Hindenburg and Ludendorff. By the winter of 1917-18, availability of food in German cities was critically low. The British naval blockade of German ports had halted food imports, while Hindenburg’s reallocation of agricultural labour had a detrimental effect on domestic production. Germany may well have sought a peace deal in mid- to late-1917, if not for two revolutions in Russia. The collapse of the Russian tsarist government in February 1917, followed in October by the overthrow of its liberal successor, the Provisional Government, spelt the end of Russia’s involvement in World War I. The Eastern Front war was now drawing to a close, allowing Germany to concentrate its forces on the Western Front. To the German High Command, the war that in early 1917 seemed as if it might drag on forever, now appeared winnable.

1. Germany and its Kaiser played a leading role in the tensions that contributed to the outbreak of World War I.

2. Germany’s initial strategy involved an attack on France through neutral Belgium, drawing Britain into the war.

3. By 1916, with the war in stalemate, Germany found itself surrounded, blockaded and short of food and supplies.

4. Control of Germany passed to its military leaders, who redeployed labour to the war effort, with dire effects.

5. Revolutions in Russia in 1917 ended the war on the Eastern Front and reignited the German war effort.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “World War I and Germany”, Alpha History, 2014, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/world-war-i/.