The design and implementation of the Weimar constitution began in late 1918, with the abdication of the Kaiser and the collapse of the monarchy. The new government, headed by chancellor Friedrich Ebert and the SPD, believed Germany should become a democratic republic. This reflected their own political values. Though Ebert and his cohort were nominally socialist, in reality, the SPD was dominated by moderates who favoured gradualism and progress rather than radical change. They also believed that transforming Germany into a representative democracy was important for the peace process. If the victorious Allies could see genuine and lasting signs of political reform, Germany would fare better in the ensuing peace treaty.

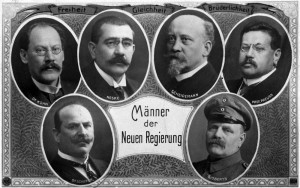

In November 1918, Ebert and his cabinet decided to convene elections for a national assembly, which would be tasked with formulating a new political system. These elections were held on January 19th 1919, just a few days after the suppression of the Spartacist uprising in Berlin. The SPD returned the most votes of any single party, its representatives filling 38 percent of seats in the assembly. Other parties with significant representation included the Catholic Centre Party (20 per cent), the liberal German Democratic Party (18 per cent) and the right-wing German National People’s Party (11 per cent). With Berlin still at risk of renewed violence, the National Assembly met in the town of Weimar on February 6th. Within a week, the assembly had formed a coalition government comprised of the SPD and other left-wing or liberal parties. Ebert was elected as the Weimar Republic’s first president, with Philipp Scheidemann as his chancellor.

The Weimar National Assembly convened for almost 18 months. During this time it completed two major tasks: the drafting of the Weimar constitution and the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles. Neither of these proved easy or popularly accepted by the German people. The broad framework for a constitution came from Hugo Preuss, a little-known lawyer who was rushed into Scheidemann’s cabinet as minister for the interior. Preuss suggested a political system modelled on that of the United States. It would be federalist but must ensure the continuation of a single German nation; it would be democratic but would contain strong executive powers for dealing with emergencies. Above all, the new constitution would be liberal: it would protect the rights and liberties of the individual.

The draft constitution was prepared in the spring of 1919. Some of its key features included:

There were flaws. The constitution had no stirring preamble that laid out a vision of a democratic Germany. The proportional voting system contributed mightily to the political fragmentation of Weimar. The electoral law that followed [the constitution] authorised representation in the Reichstag for every party with 60,000 votes. The powers granted to the president in emergency situations were too extensive. But the flaws in the constitution had less to do with the political system it established than with the fact that German society was so fragmented. A less divided society, and one with a more expansive commitment to democratic principles, could have made it work.

Eric D. Weitz, historian

Federalism. The Weimar constitution recognised the seventeen German states and allowed for their continuation. Law-making power would be shared between the federal Reichstag and state Landtags. The national government would have exclusive power in areas of foreign relations, defence, currency and some other areas.

The Reichstag. The German parliament (Reichstag) was elected every four years, or sooner if the need arose. All German citizens aged 20 or more would be permitted to vote in Reichstag elections, regardless of status, property or gender. All elections would utilise a secret ballot. Reichstag deputies would be chosen using a system of proportional representation, meaning that parties would receive seats in proportion to their total votes.

The Chancellor. The broad equivalent of a Westminster-style prime minister, the Chancellor was responsible leading the government of the day. The Chancellor was chosen, appointed and dismissed by the President and led a cabinet of ministers. The Chancellor did not have to be a sitting member of the Reichstag, though to pass legislation they certainly required support within the legislature.

The President. The German President was elected by the people and served a seven-year term. The President was head of state and was not part of the Reichstag. In principle, the president was not intended to exercise much power or personal prerogatives, other than the appointment of the chancellor and ministers. However Article 48 of the constitution granted the president considerable powers in the event of an ’emergency’, allowing him to rule by decree and override the Reichstag, to suspend civil rights and to deploy the military.

This constitution made the Weimar Republic one of the most democratic and liberal political systems of its time. It provided for universal suffrage, contained a limited bill of rights and offered a proportional method of electing the Reichstag. But this was to prove a risky experiment, giving such an expansive liberal democracy to a nation and a people who had previously known only rigid monarchic and aristocratic rule. This view is echoed by historian Klaus Fischer, who suggested it was “doubtful whether such a democratic constitution could work in the hands of a people that was neither psychologically nor historically prepared for self-government”. Even Hugo Preuss, the man who drafted much of the constitution, wondered aloud whether such a progressive system should be given to a people who “resisted it with every sinew of its body.”

1. German politicians met in the city of Weimar to form a new government since street-fighting made Berlin unsafe.

2. They drafted, accepted, debated and approved one of the most liberal constitutions in the world at that point.

3. It replaced the king with a president, who was not part of the Reichstag, though he could exercise emergency powers.

4. The Reichstag was retained as a parliamentary body, though its electoral system allowed minor parties to win seats.

5. The nation was effectively ruled by a chancellor, who operated within the Reichstag but was appointed by the president.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The Weimar Constitution”, Alpha History, 2014, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/weimar-constitution/.