Weimar cabaret was a feature of late 1920s Germany, which has become known for its high living, vibrant urban life and the popularisation of new styles of music and dance. Having previously lived under an authoritarian government, where entertainment and social activities were tightly regulated, many Germans thrived on the relaxed social attitudes of Weimar. The influx of American money and the economic revival of the mid to late 1920s encouraged celebration, spending and decadence. According to some historians, this extravagance may have been driven by a realisation that this prosperity was both artificial and temporary. Many Germans spent big and partied hard, aware that both the economy and the government were destined to fail. The late Weimar era was marked by liberal ideas, new forms of expression and hedonism (pleasure-seeking). Weimar music, dance and entertainment were criticised by radicals on both sides of politics. The socialists believed it represented the wastefulness of capitalism; right-wing groups and reactionaries claimed it was evidence of weak government, resulting in moral decay and corruption.

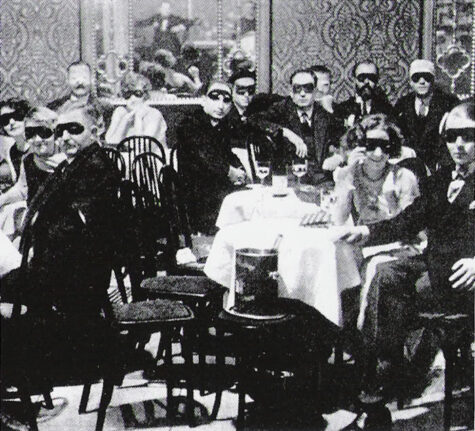

The late Weimar era, or ‘Golden Age of Weimar’, was particularly known for its cabarets. Most cabarets were restaurants or nightclubs where patrons sat at tables and were entertained by a procession of singers, dancers and comedians atop a small stage. Cabaret was, in fact, a French invention that dated back to the 1880s. Perhaps the most famous of all French cabarets, the Moulin Rouge, was notorious for allowing lewd dancing and employing prostitutes as dancers and waitresses. The German form, Kabarett, was at first more conservative and low-key. Berlin’s first cabaret nightclub dated back to 1901, however during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II, German cabarets were not permitted to perform or promote bawdy humour, provocative dancing or political satire.

After World War I cabarets became enormously popular across Europe – and nowhere were they more popular than Germany. The Weimar government’s lifting of censorship saw German cabarets transform and flourish. Entertainment in the cabaret of Berlin, Munich and other cities was soon dominated by two themes: sex and politics. Stories, jokes, songs and dancing were laced with sexual innuendo. As the 1920s progressed this gave way to open displays of nudity, to the point where most German cabarets had at least some topless dancers. Some cabarets were patronised by gay men, lesbians and transvestites; once forced to conceal their sexuality, they seized upon the liberality of the cabaret scene to openly display and discuss it. The reactionaries and wowsers loathed it, of course. The Austrian writer Stefan Zweig condemned Berlin’s cabaret scene, and the effect it was having on the nation’s social fabric:

Berlin transformed itself into the Babel of the world. Germans brought to perversion all their vehemence and love of system. Made-up boys with artificial waistlines promenaded along the Kurfiirstendamm … Even [ancient] Rome had not known orgies like the Berlin transvestite balls, where hundreds of men in women’s clothes and women in men’s clothes danced under the benevolent eyes of the police. Amid the general collapse of values, a kind of insanity took hold of precisely those middle-class circles which had hitherto been unshakeable in their order. Young ladies proudly boasted that they were perverted; to be suspected of virginity at sixteen would have been considered a disgrace in every school in Berlin.

The cabarets also provided Germans with an outlet for political views and criticism. A good deal of the stand-up comedy on cabaret stages was done by ‘political humourists’, who ridiculed all points along the political spectrum. Their mockery, parody and satire were ‘anything goes’; no leader, party, policy or idea was spared. Some of it was personal rather than political: Friedrich Ebert was mocked for his weight, while the appearance and mannerisms of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler were ridiculed during the late 1920s. But some cabaret performers asked more substantial political questions. One asked ‘How socialist is the Social Democratic Party?’ while another queried whether Germany was really a republic or was still being run by aristocrats and industrialists. Many comperes and comedians harked back to the ‘good old days’ of imperial Germany: when taxes were low, bread was cheap and meat was plentiful. Cabaret songs often contained a political subtext. Mischa Spoliansky’s popular tune, It’s All A Swindle (1931), was a typical example:

Politicians are magicians

Who make swindles disappear

The bribes they are taking

The deals they are making

Never reach the public’s ear

The left betrays, the right dismays

The country’s broke – and guess who pays?

But tax each swindle in the making

Profits will be record-breaking

Everyone swindles some

So vote for who will steal for you.

1. After decades of restrictive, authoritarian government, Weimar was a period of social liberalisation.

2. In post-1924 economic revival saw many seek new forms of leisure and entertainment, like Kabarett.

3. German cabaret entertainment revolved around themes of sexual liberation and political criticism.

4. The cabarets followed no political line: any party or leader was subject to criticism or mockery.

5. Many feared the impact the ‘cabaret culture’ was having on German society and public morality.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “Weimar cabaret”, Alpha History, 2014, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/weimar-cabaret/.