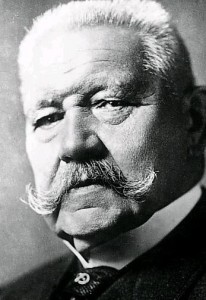

Paul von Hindenburg was born in 1847, the son of a Prussian aristocrat and his commoner wife. Like other scions of the Junker elite, the young Hindenburg was sent for a military education at cadet schools. In 1866 he was shipped off to the Austro-Prussian War, where he experienced battle before his 19th birthday. Hindenburg also served in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) and as an adjutant attended the ceremony that formally unified Germany in 1871. In 1903 he was promoted to the rank of general. In 1911 the 64-year-old Hindenburg left the military, intending to retire to his sizeable land holdings in Prussia. But he was recalled after the outbreak of World War I and sent to fortify East Prussia against a Russian offensive, a mission he had completed by September 1914.

In late 1914 Hindenburg was given his own army and put in charge of the Eastern Front, where he achieved several notable victories. These successes saw Hindenburg become enormously popular in Germany, where he acquired a reputation as both a brilliant military tactician and an inspirational leader. But his reputation was overstated and possibly undeserved, since many of Hindenburg’s notable successes were largely the work of subordinates, like Erich Ludendorff. In contrast, the Western Front failures of chief of staff Erich von Falkenhayn left his reputation in tatters. Hindenburg was promoted to field marshal and, in August 1916, he replaced von Falkenhayn as commander-in-chief. For the rest of the war, Hindenburg and Ludendorff ruled Germany as de facto military dictators – deciding military tactics, determining economic policy and bypassing the civilian government.

In October 1918, with Germany’s defeat imminent, Hindenburg left the army a second time. The following year he appeared before a commission of inquiry into the war, where he fuelled the Dolchstosselegende (stab in the back legend) by telling the Reichstag that he believed the German army had not been defeated on the front, it had been undermined and betrayed in Berlin. Politically, Hindenburg remained committed to rule by the Prussian monarchy; he loathed socialism and the SPD and expressed doubts that democratic parliamentary government could ever succeed in Germany. By 1920 he had disappeared from public life again, beginning his retirement as a wealthy Prussian aristocrat.

“His cross-party nomination [in 1925] was presented as an antithesis to Weimar’s parliamentary bickering and social discord. Carefully suppressing the political bargaining that had secured his nomination, the right portrayed Hindenburg as a symbol of national unity towering above the party strife, a ‘man who leans neither left or right, not towards the monarchy and not towards the Republic, but only knows his duty to serve the state and the people’. In emphasising the theme of national unity the right-wing campaign could build upon the Hindenburg myth. The motifs of loyalty, duty and sacrifice also featured equally prominently.”

Anna von der Goltz, historian

The death of Friedrich Ebert in February 1925 thrust Hindenburg back into the spotlight – and into Weimar political life. The old general was lobbied by former military colleagues, particularly Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who urged him to run for the presidency, chiefly to keep it out of hands of the SPD or Catholic Centre Party. Though he initially said no, Hindenburg eventually agreed to stand. His path was cleared when the DVP candidate, Karl Jarres, stepped aside and allowed Hindenburg to take his place. In the April run-off election, Hindenburg was backed by the four main right-wing parties (the DVP, DNVP, BVP and NSDAP). He was also supported by the majority of the German press, which promoted his personal conduct and decency, his status as a war hero and his reputation – deserved or not – for strong and intelligent leadership. Hindenburg won 48 per cent of the vote and narrowly defeated the Centre Party candidate, Wilhelm Marx (45 per cent).

Hindenburg’s election caused shock waves around Europe, where Hindenburg was still reviled for his role in World War I. Paris and London were horrified at Hindenburg’s election as head of state of a supposedly a democratic republic. Some interpreted it as a revival of German authoritarianism and the first step towards the implementation of a military dictatorship. But while Hindenburg would have welcomed the return of the monarchy, he had no intentions of betraying the constitution. For much of his nine years in the presidency, Hindenburg acted as a benign, apolitical and non-interventionist head of state. He remained aloof from party politics and bickering; he did not interfere in policy formation, and in most cases, he acted on the advice of his ministers. Hindenburg’s commitment to constitutional and democratic processes was not easy to maintain, given that he was surrounded by an inner circle of advisers who were mostly anti-democratic. It is to Hindenburg’s credit that he was able to resist their attempts to undermine and sabotage the republic – at least until late 1932.

1. Hindenburg was a career military officer of Prussian aristocratic birth who was recalled to service in 1914.

2. His Eastern Front success earned him fame and adulation, though his own part in this was exaggerated.

3. After the war, Hindenburg retired from public life – but not before perpetuating the ‘stab in the back’ legend.

4. After the death of Friedrich Ebert, Hindenburg agreed to stand for the presidency. Supported by right-wing parties and the press, he was a narrow victor in 1925.

5. As president, Hindenburg acted with dignity and caution. He distanced himself from party politics and sought to uphold the constitution and republic.

© Alpha History 2018. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The presidency of Paul von Hindbenburg”, Alpha History, 2018, accessed [today’s date], http://alphahistory.com/weimarrepublic/paul-von-hindenburg/.