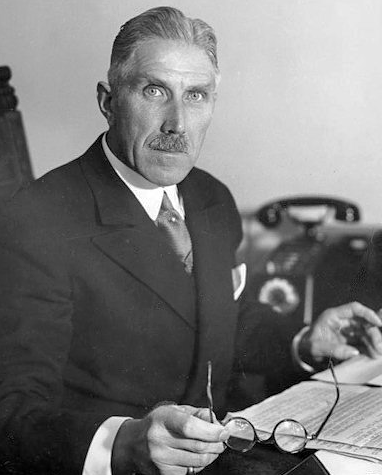

Franz von Papen (1879-1969) was a German military officer and politician, best remembered for his role in bringing Adolf Hitler to the chancellorship. Born to a family of Catholic aristocrats in Westphalia, Papen joined the military as a cadet, graduating with a commission in 1897. Elitist and militarist by nature, Papen was loyal to Wilhelm II and entirely supportive of the Kaiser’s war plans. Papen travelled to the United States as a military attaché in mid-1914 but was later expelled for planning and supplying acts of sabotage against American war industries. He returned to Germany and spent the rest of the war commanding combat battalions on the Western Front and in the Middle East. After the war, Papen joined the Catholic Centre Party and sat in the Prussian legislature. In the mid-1920s he broke with members of his own party, outraged by their coalition with the Social Democratic Party (SPD), and supported Paul von Hindenburg. Papen served as chancellor for five months in 1932 before convincing Hindenburg to appoint Hitler to the role. In these extracts from his memoirs, published in 1953, Papen offered his views on the problems and failures of the early Weimar Republic:

On the demise of Imperial Germany:

“The world I had known and understood had disappeared. The whole system of values into which I had integrated myself and for which my generation had fought and died had become meaningless. The Kaiser’s Empire and the Prussian monarchy, both of which we had regarded as permanent institutions, had been supplanted by a largely theoretical republic. Germany was defeated, ruined, her people and institutions a prey to chaos and disillusionment.”

“In the tumult of the post-war period, the duty of all conservative forces was to rally under the banner of Christianity, in order to sustain in the new republic the basic concepts of continuing traditions. The Constitution approved at Weimar in 1919 seemed to many a perfect synthesis of Western democratic ideas. But the second paragraph of its first article proclaimed the false philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau: ‘All power derives from the people’. This thesis is diametrically opposed to the teachers and traditions of the Roman Catholic Church… Now we had to accept the proposition that the State was the ultimate factor in our affairs, and its institutions, both administrative and parliamentary, the final repository of authority.”

On the Allies and post-war Germany:

“The grave errors and injustices contained in the Versailles Treaty can only be explained by the state of hysteria engendered in the Allied powers by years of hate-filled and untrue propaganda. Wilson’s Fourteen Points were greeted with immense relief in Germany. We were all convinced that the United States, having proved the decisive factor in the victory of the Allies, would play the principal part in the peace negotiations… We wished for nothing better than to build a new world, as equal partners, conferring with other nations on our mutual difficulties. We still believed in Germany’s historic mission as the stabilising factor in Central Europe. The competition and rivalries… seemed a thing of the past. We no longer represented a danger to anyone.”

“Both the Central and State governments suffered from the same constructional fault. Legislative powers were confined exclusively to a single chamber and there was no higher authority to provide for their correction and revision… There was also the problem of a highly artificial electoral law… I was particularly opposed to the list system of voting. It was praised as the most democratic in the world [but] under this system we finally had over 30 parties… Any eccentric, or group of eccentrics was almost sure of getting at least one member into Parliament on the reserve list of votes. The consequent splintering of representation amounted to the suicide of democracy.”

On the hyperinflation of 1923:

“People abroad have very little conception of the magnitude of this disaster. At the end of the inflation, I can remember how wages and salaries had to be paid daily because the money received retained only a fraction of its worth at the end of another 24 hours. The Central Bank was unable to print money fast enough and many cities issued their own currency so that it became impossible to continue any ordered financial policy. It took a billion marks to purchase what one mark had bought before, and this meant that all savings, mortgages, pensions and investment incomes were completely worthless, and those without material belongings lost their entire capital. Those who had contributed to the many war loans lost the most. The middle classes, the artisans, pensioners and officials were proletarianised in the process. The industrious workman who had acquired a little property and substance had the basis of his economic existence destroyed and became a recruit to class warfare. This revolution in the social order provides the clue to the attraction of Marxist ideologies and of Hitler’s programme, born in these difficult days.”