The Scissors Crisis was an economic problem that confronted Soviet Russia in the early to mid-1920s. It was a consequence of the New Economic Policy (NEP) of 1921, which stimulated recovery in Russian agricultural production. Under war communism, thousands of peasants abandoned the land in order to escape famine, grain requisitioning and the much-feared CHEKA. Under the NEP, which ended requisitioning and allowed Russians to buy and sell surplus produce, peasants returned to work the land. Improved weather conditions also helped, as the catastrophic droughts of 1920-21 were broken by more consistent rainfall. The 1922 and 1923 harvests were extremely successful. With more produce on the market, food prices more than halved between August 1922 and February 1923. By 1925 Russian agricultural production was in its best shape for more than a decade, grain production and livestock numbers approaching pre-World War I levels. The Soviet government helped by becoming the monopoly purchaser and distributor of grain and setting price levels. This prevented gouging and profiteering and kept food prices low.

While Russian agriculture was recovering, the industrial sector was progressing far more slowly. There were several reasons for this. Industrialisation required capital, expertise and infrastructure, all of which were in short supply in post-revolutionary Russia. Factories required a large amount of labour, however, seven years of war and miserable conditions had depleted the nation’s urban workforce. Many factories and manufacturing centres lacked both experts and unskilled workers; they also utilised inefficient practices that limited production and drove up costs. Inadequate supplies of essential raw materials such as oil, coal and steel also hampered production. Because of these factors and others, the industrial and manufacturing sectors recovered at a much slower rate than agriculture. Many manufactured commodities were short in supply and hard to locate. This scarcity was exploited by the Nepmen (merchants, traders and retailers who sold manufactured goods at a profit).

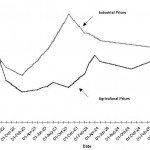

As demand for industrial and manufactured items increased, so did their prices. By late 1923 the cost of manufactured items had increased to almost three times their prices in 1913. In contrast, food prices were around 90 per cent of their 1913 levels. When shown on a line graph this widening price gap resembled a pair of scissors with the blades open, hence the name ‘Scissors Crisis’. But the Scissors Crisis was not just economic theory: it entailed real problems for ordinary Russians. Low food prices meant that farmers going to market received smaller sums for their crops; high commodity prices meant they could not afford to purchase manufactured goods. Without enough surplus cash to purchase equipment, machinery or building materials, Russian farmers could not embrace new methods or increase their productivity. Low crop prices were also a disincentive to production. Under war communism, many farmers saw no need to work hard when surplus grain would be seized by the state. During the Scissors Crisis, many farmers saw no need to work hard when surplus grain brought miserable prices at market.

“In 1923 the government reacted to the crisis by imposing price controls on urban products commonly consumed by villagers, and in the following year it resumed grain exports, thus raising food prices. In that way, it restored some equilibrium to rural-urban trade at the cost of urban consumers… But no foundation had been laid for long term growth, while party members were given economic reasons to resent the NEP, to add to the political ones.”

Geoffrey A. Hosking, historian

The Soviet regime responded to the scissors crisis by introducing policies to force down the price of manufactured goods. First, in 1923 it resumed exports of grain. This not only provided the regime with funds for infrastructure, it also reduced the amount of surplus grain in Russia and caused food prices to slowly rise. Moscow also tightened its grip on under-performing industries, setting ambitious production targets, cutting staff numbers in labour-intensive sectors and making production more cost-efficient. Stores and market holders who sold commodities at inflated prices were forcibly closed (more than 250,000 were shut down in 1923-24). Meanwhile, the Commissariat of Trade was given an expanded role as a distributor and retailer of consumer goods, reducing the impact of profiteering Nepmen. In other words, the Soviet government itself became involved in buying and selling manufactured items at more reasonable prices. These measures produced a gradual improvement in the situation. By April 1924 industrial prices had begun to fall and the blades of the ‘scissors’ were slowly closing. The Scissors Crisis was never finally resolved, however. Shortages of industrial and manufactured goods remained a constant problem under the NEP.

1. The Scissors Crisis was an economic problem, triggered by the New Economic Policy (NEP), that appeared in Soviet Russia in the mid-1920s.

2. As agricultural production rapidly increased, food prices fell. In contrast, shortages of industrial and manufactured goods caused their prices to rise.

3. The growing disparity between food and commodity prices, when drawn on a line graph, represented a pair of open scissors, hence the name of the crisis.

4. The real impact of the Scissors Crisis was felt by ordinary Russians, particularly the farmers, who received little in return for their surplus food crops and could not afford to purchase manufactured goods.

5. The Soviet government partially resolved the Scissors Crisis by introducing price controls, forcing down industrial costs, cracking down on profiteering traders and allowing the Commissariat of Trade to establish trading cooperatives.

© Alpha History 2014. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, John Rae and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

J. Llewellyn et al, “The ‘Scissors crisis'” at Alpha History, https://alphahistory.com/russianrevolution/scissors-crisis/, 2014, accessed [date of last access].