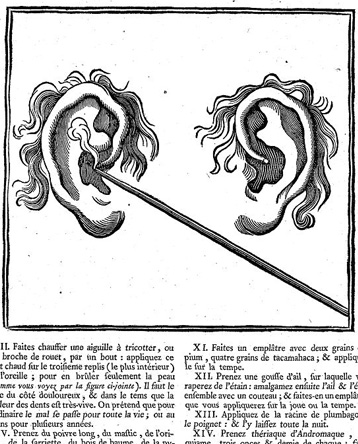

Noel Chomel (1633-1712) was an estate manager and parish priest from central France. In 1709, three years before his death, Chomel published his lifelong collection of handy hints, recipes and medical receipts. The Dictionnaire Oeconomique, as it was titled, became one of the most popular household almanacs of the 18th century. Over the next 70 years it was reprinted numerous times in several languages, including French, German and Dutch.

The first English edition was translated and updated by Cambridge botany professor Richard Bradley and published in London in 1725. This edition contained advice on everything from cooking to card games, from making soap to managing livestock. Many of its medical remedies called for the use of dead animals and excrement. For example, for “those who piss a bed”:

“Take some rat or mouse turd, reduce it into powder and putting about an ounce of it in some broth, take it for three days together. It is an excellent remedy for this imperfection. There’s [also] nothing better for persons who piss in their sleep… than to eat the lungs of a roasted kid [or] to drink in some wine a powder made of the brain or testicles of a hair…”

For an anal fistula, a “hollowy oozy ulcer in the posteriors”:

“Take a live toad, put it into an earthen pot that can bear the fire, cover it so that it cannot get out, surround it with a wheel fire and reduce it into powder… Lay this powder upon the fistula, after you have first washed it with warm wine or the urine of a male child.”

Lastly, for severe or bloody dysentery:

“Take the powder of a hare, dried and reduced into powder, or the powder of a human bone, and drink it in some red wine. Gather the turd of a dog that for the space of three days has gnawed nothing else but bones, dry it and reduce it into powder, and let the patient drink it twice a day with milk.”

Source: Noel Chomel & Richard Bradley, Dictionnaire Oeconomique, 1725 ed. Content on this page is © Alpha History 2019-23. Content may not be republished without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use or contact Alpha History.