When the Good Friday Agreement was signed in April 1998, the majority of people responded with praise and optimism. To outsiders, the Belfast Agreement seemed to offer a realistic chance of peace and stability in Northern Ireland. Most Republicans had demonstrated a commitment to exchanging paramilitary violence for political engagement. Major parties had come together to negotiate peacefully and sincerely. Each of the stakeholders had acknowledged the views of the other; each had made important compromises and concessions. The final document furnished Northern Ireland with political institutions that offered a reasonable prospect of stability and success. Those with a deeper understanding of the issues were more cautious and pragmatic. Drafting the Good Friday Agreement was an achievement work celebrating – but working together, implementing its standards and maintaining the peace posed an even greater challenge.

The world applauds

International reactions to the Belfast Agreement were commendatory and optimistic. Pope John Paul II welcomed the agreement, urging Northern Irelanders to “take the path of peace together” and “turn their backs on hatred and violence”. United States president Bill Clinton, who had played a personal role in finalising the agreement, called it Northern Ireland’s “best chance for peace in a generation”. Former British prime minister John Major heaped praise on his successor Tony Blair and Irish taoiseach Bertie Ahern, saying “I don’t care about their political labels. I just care that they have done it and I want their achievement to thrive”. George Mitchell, the American whose leadership helped secure the agreement, reported that he had “been in politics for 30 years and never have I felt this sense of gratification and responsibility”.

This adulation was accompanied by cautious realism – and indeed some pessimism. Many were concerned that the agreement had been forged under stress and in poor spirit. Unionists and Nationalists had barely spoken to each other during negotiations; both sides had threatened to walk out of the talks; the final session had lasted a marathon 33 hours; there was no handshake or joint press conference to finalise the agreement. All involved understood the fragility of the Belfast pact. Its success would depend on the good faith and future actions of its stakeholders. George Mitchell, while pleased that agreement had been reached, was guarded in his hopes for the future. Mitchell noted a “presumption of bad faith” between Unionists and Nationalists and warned the agreement could collapse within 18 months if both parties were unable to work together. Speaking to the BBC, Mitchell posited several critical questions: “Will the assembly be able to get itself organised? Will it be able to operate as an effective legislative body? Will the North-South bodies work to the mutual benefit of north and south?”

There were even more grumblings within Northern Ireland. Unionists and Loyalists were split on whether the agreement was a positive step. David Trimble continued to support it but around half his colleagues in the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) expressed opposition or at least strong concerns. Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Ian Paisley, whose party abstained from the peace talks, denounced the agreement as “the mother of all treacheries”. He condemned Blair for orchestrating the agreement – and when Queen Elizabeth II voiced her support Paisley said “she has become a parrot”. Members of the UK Unionist Party (UKUP), another Loyalist party, described Trimble as a traitor. Unionist politician William Ross called the agreement “a full-blown surrender to IRA demands”. The agreement was also opposed by ultra-Republican groups. Founded in November 1997, weeks into the peace talks, the Real IRA rejected any negotiated peace and maintained its commitment to armed struggle. The Continuity IRA and a handful of dissidents in Sinn Fein expressed similar views.

Implementing the agreement

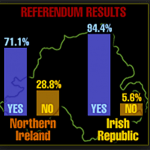

Implementation of the Good Friday Agreement required public endorsement by a joint referendum in Northern Ireland and the Republic. This referendum was held on May 22nd 1998. Voters in Ireland were asked to approve changes to Articles Two and Three of the constitution, which claimed sovereignty over Northern Ireland. These amendments were passed almost 94.5 percent of voters. In Northern Ireland, voters were asked to indicate ‘yes’ or ‘no’ whether they supported the Belfast Agreement. Most parties advocated supporting the agreement while only two parties, the DUP and UKUP, campaigned against it. Tony Blair, concerned that Northern Irelanders might vote down the Belfast Agreement, simplified it by making five core promises. More than 81 percent turned out to vote, a much higher figure than is usually the case. A total of 676,966 people, or 71.1 percent of turned out voters, chose to support the agreement. Mo Mowlam called the result “a resounding victory for all the people of Northern Ireland”.

A month later, on June 25th, Northern Irelanders went to the polls again, this time to elect their new Assembly. Almost 70 percent of registered voters turned out to cast a ballot. Unionists, as expected, held sway in the new Assembly. The UUP became the largest party, winning 28 seats. John Hume‘s Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) became the largest Nationalist party, finishing with 24 seats. Paisley’s DUP ended up with 20 seats and Sinn Fein 18, with minor parties holding the remaining 18. The new Assembly met at Stormont for the first time on July 1st. One of its first orders of business was to elect a First Minister and Deputy First Minister, as outlined in the Belfast Agreement. These roles went to UUP leader David Trimble and SDLP deputy leader Seamus Mallon respectively. The Assembly then set about planning executive ministries and deciding how they would be apportioned among different parties.

Sectarianism revived

At this point, it appeared Northern Ireland had reached a political milestone. On the streets, however, the situation remained tense. Sectarianism reared its ugly head during the July marching season, this time at Drumcree in Portadown, County Armagh. In February 1998 the British government, anticipating clashes between Protestant marchers and Nationalists, passed the Public Processions Act. This legislation established a seven-person Parades Commission tasked with overseeing and managing parade routes and activities, to avoid antagonising either community. On June 29th the Parades Commission banned the Orange Order from marching on its traditional but provocative route along Garvaghy Road. Thousands of affronted Orangemen and Loyalists headed to Portadown to protest the ban, while 2,000 police and soldiers erected barricades to prevent them entering Catholic areas. The protestors responded by occupying Drumcree Church, digging a trench and erecting barbed wire.

The events in Portadown sparked sectarian clashes and violence across Northern Ireland. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) recorded a total of 24 shootings during this period, though none were fatal. The worst incident occurred in Dunloy, a small village in County Antrim, 55 miles north of Portadown. On July 12th, the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne, Loyalists firebombed a house belonging to Chrissie Quinn. The resulting fire killed her children Richard, Mark and Jason, aged eight to ten. Quinn was Catholic but was raising her sons as Protestant. The murder of three young boys caused outrage across Northern Ireland and was condemned by several Protestants. The sectarian violence soon withered away, though scores of protestors remained entrenched at Drumcree.

The ultra-Republicans

The implementation of the Good Friday Agreement was also marred by Republican violence. The Provisional IRA’s July 1997 ceasefire cleared the way for peace talks – but it also outraged militant Republicans seeking to continue the armed struggle. Formed after the 1994 ceasefire, the Continuity IRA reactivated and launched a series of attacks through 1998. An even more deadly group formed in November 1997 as a Provisional IRA splinter group. The Real IRA began its operations in January 1998. Led by former IRA quartermaster Michael McKevitt, the Real IRA attacked security forces, government buildings and commercial targets, usually with car bombs or mortars. In August 1998 Real IRA operatives detonated a large car bomb in downtown Omagh, County Tyrone. As with similar Real IRA attacks detonation was preceded by telephone warnings – but these warnings were imprecise and confused, resulting in police herding civilians towards the bomb rather than away from it. The blast killed 29 people, making it the deadliest single terrorist incident of the Troubles. Despite widespread grief and outrage, the Good Friday Agreement held firm and the peace process continued.

Stalemate to devolution

“Whatever voters thought, it was clear that the British and Irish governments were only temporarily deterred in their efforts to implement the Good Friday Agreement. No atrocity, from the Canary Wharf bomb onwards, had deflected what became known as the ‘peace process’. A series of delays and suspensions, mixed with murders, civil disturbances, breaches of ceasefires and allegations of gunrunning… lead the two governments to view their chosen path as hopeless. As we now know, their perseverance led to a resumption of devolution in an apparently more stable form. [This] came to be widely regarded as the crowning achievement of Tony Blair’s controversial premiership and a triumph for Anglo-Irish cooperation.”

Graham Gudgin, academic

The terms of the Belfast Agreement required the Northern Ireland Assembly to devise a means for forming an Executive that was acceptable to all parties. Britain would defer devolution and maintain Direct Rule until this was achieved. The Assembly met through 1998 and early 1999 but failed to reach agreement on the composition of the Executive. The main stumbling block was decommissioning: Unionists refused to share the ministry with Sinn Fein until the IRA had laid down their weapons. Negotiations were also frustrated by disagreements over prisoner releases and occasional paramilitary attacks. Tony Blair set the Assembly two deadlines – April 2nd and June 30th 1999 – for forming an executive but no agreement was reached by either date.

In August 1999, with the Good Friday Agreement on the verge of collapse, George Mitchell returned to Belfast to thrash out a deal between Unionists and Sinn Fein. They reached an agreement on November 16th, after 11 weeks of talks. Mitchell’s plan involved appointing ministerial portfolios using the d’Hondt system. Named after a 19th-century Belgian mathematician, the d’Hondt formula allocates ministries to parties based on their number of seats. The first executive, for example, contained three UUP ministers, three from the DUP, three from the SDLP and two from Sinn Fein. These ministers were nominated by the Assembly and sworn in on November 29th 1999. With the Executive now finalised, the path was clear for Britain to finalise the devolution of power to Northern Ireland. This was marked with proclamations and ceremonies on December 2nd 1999, bringing more than 27 years of Direct Rule to an end.

1. The Good Friday Agreement attracted worldwide praise and a sense of optimism about Northern Ireland – though many knew implementing the agreement would be just as difficult.

2. The agreement triggered a split in the Unionist movement. It was condemned by Ian Paisley and the DUP, as well as the UKUP and some within David Trimble’s own UUP.

3. Joint referendums in May 1998 endorsed the agreement, Northern Irelanders voting 71.1 percent to accept it and the Republic voting 94.5 percent in favour of its changes.

4. A new Northern Ireland Assembly was elected and two First Ministers were chosen. They set about forming an Executive, amid rising sectarianism triggered by protests at Drumcree.

5. Disputes over decommissioning prevented Unionist acceptance of an Executive containing Sinn Fein members. This was resolved in late 1999, leading to devolution on December 2nd.

Tony Blair’s five promises on the eve of the referendum (1998)

Gerry Adams on the role of Sinn Fein post-Good Friday (1998)

Tony Blair addresses the Irish parliament on the Good Friday Agreement (1998)

© Alpha History 2017. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole and S. Thompson, “Implementing the Good Friday Agreement”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/implementing-good-friday-agreement/.