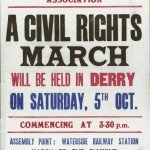

By late 1967 the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland had grown and intensified. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) began to organise anti-discrimination protests. These demonstrations were frequently blocked by the Northern Ireland government, an action that only reinforced NICRA’s claims of discrimination and deepened resentment. In August 1968 members of NICRA met with delegates from the Derry Housing Action Committee (DHAC) and planned a protest march for October 5th. On October 1st the Apprentice Boys of Derry, a Protestant group, provocatively scheduled a march of their own – at the same time and along the same route. This provided the government with a pretext for banning the NICRA march; it did so on October 3rd. NICRA proceeded with the October 5th march regardless. It was attended by around 1,000 people, including several members of the British and Northern Ireland parliaments. The march began peacefully but when participants defied police orders to disperse, Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) officers cleared them with baton charges and a water cannon. At least 77 civilians and four policemen were injured. A subsequent inquiry into the events of October 5th reported that:

“It appears… on the evidence that at this stage batons were used by certain police officers without explicit order, although this is denied by the police. We regret to state that we have no doubt that both Mr Fitt and Mr McAtteer were batoned by the police, at a time when no order to draw batons had been given, and in circumstances in which the use of batons on these gentlemen was wholly without justification or excuse.”

From marches to mayhem

The brutal dispersal of the October 5th NICRA march triggered three days of rioting across Derry. On October 9th approximately 2,000 university students marched through central Belfast in protest; this march was blocked by Loyalist demonstration. These marches gave rise to two new civil rights organisations: the People’s Democracy (PD) and the Derry Citizens’ Action Committee (DCAC). On October 16th around 1,400 students from Belfast’s Queens University marched through the centre of the city to rally outside City Hall. Nationalist Party MPs also protested the government’s one-sided handling of the crisis by withdrawing from the Northern Ireland parliament. From late October through to December protest groups organised a series of civil rights marches, rallies and sit-ins in Belfast and Derry. These demonstrations were banned by the government on November 13th. In contrast, Orange Order and Loyalist marches were deemed to be ceremonial rather than political, so were permitted to continue. Civil rights groups continued to defy the government ban but their marches were broken up by an increasingly violent RUC. These police actions were carried out under the auspices of the Special Powers Act that prime minister Terence O’Neill had promised to abolish.

On November 22nd O’Neill attempted to defuse the tensions over civil rights by proposing a package of reforms. Among the changes suggested were the replacement of the local administration in Derry; new guidelines for housing allocations, based on a needs-based points system; the creation of an independent ombudsman to investigate discriminatory or corrupt housing allocations; reforms to local government voting rights; and the repeal of the 1922 Special Powers Act, which gave the government and police sweeping powers to maintain public order. But while O’Neill’s proposals appeared a step in the right direction, they proved counter-productive. Most Unionists rejected the reforms, considering them a stepping stone towards Catholic infiltration of the government. Nationalists also expressed discontent, claiming the reforms – particularly the suggested changes to local government voting rights – were not extensive or meaningful enough. NICRA’s leadership rejected O’Neill’s proposed electoral reforms, calling for “one man, one vote”. One civil rights campaigner declared that “accepting a milder form of discrimination is still accepting discrimination”.

O’Neill pleads for calm

“And then we came to Burntollet Bridge, and from lanes at each side of the road a curtain of bricks and boulders and bottles brought the march to a halt. From the lanes burst hordes of screaming people wielding planks of wood, bottles, laths, iron bars, crowbars, cudgels studded with nails, and they waded into the march beating the hell out of everybody… Before this onslaught our heads-down-arms-linked tactics were no use whatever, and people began to panic and run.”

Bernadette Devlin, politician

O’Neill attempted to sell his plans for reform while trying to restore order. On December 9th he appeared on television and declared that “Ulster stands at the crossroads… What kind of Ulster do you want? A happy and respected province in good standing with the rest of the United Kingdom? Or a place continually torn apart by riots and demonstrations and regarded by the rest of Britain as a political outcast?” O’Neill’s impassioned speech was well received and contributed to a month-long reduction in protests and rioting. Violence ignited again in January, however, following a series of marches and protests. On New Year’s Day 1969 around 40 members of People’s Democracy began a four-day civil rights march from Belfast to Derry. The number of marchers increased to several hundred as the procession moved west. On January 4th the marchers were attacked in Burntollet by around 200 Loyalists armed with sticks, clubs and stones, an ambush described by Bernadette Devlin. Numerous marchers were injured and 13 required hospitalisation. It soon emerged that a company of RUC officers assigned to accompany the marchers had done little to protect them. The march continued but there was more rioting and violence when the procession entered Protestant areas of Derry.

Terence O’Neill responded to the events of January 4th by issuing a statement urging calm, though it was less tolerant and conciliatory than his earlier remarks. Four days later O’Neill travelled to London to brief British ministers on the worsening situation. He also convened an official inquiry, overseen by Lord Cameron, to investigate the causes of the growing unrest. But O’Neill’s hold on power in Northern Ireland was now fragile. His reforms had widened divisions within his own Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), leading to the resignation of deputy prime minister Brian Faulkner and health minister William Morgan in late January 1969. O’Neill attempted to strengthen his position by calling a snap election for February 24th. The UUP won 36 seats, much more than any other party, but it lacked a decisive majority to proceed with the reforms. O’Neill was almost defeated in his own electorate, Bannside, by hardline Unionist and conservative Christian Ian Paisley, who secured almost 39 percent of the vote. Following O’Neill’s reelection Loyalist paramilitary groups bombed infrastructure around Northern Ireland, disrupting Belfast’s supplies of power and water. These incidents undermined confidence in O’Neill’s government, which had come to be seen as weak and indecisive. On April 28th Terence O’Neill resigned as prime minister, succumbing to demands from Loyalists and members of his own party.

1. The Northern Ireland civil rights movement intensified through 1968. Groups like NICRA organised rallies and marches in 1968, however these marches were often declared illegal by the Unionist government.

2. In October the RUC broke up a NICRA march in Derry with baton charges and water cannon, injuring 77 people. This heavy-handedness triggered days of rioting and a government ban on future civil rights marches.

3. Loyalist marches, in contrast, were deemed to be ceremonial rather than political, so were allowed to continue. Nationalists also accused the RUC of failing to take action against Loyalist violence.

4. In November 1968 prime minister Terence O’Neill announced a series of social and electoral reforms, designed to ease tensions. These reforms outraged Loyalists and failed to satisfied Nationalists.

5. As tensions continued to rise, O’Neill made an impassioned plea for unity. Protests, marches and violence flared up again in January 1969. The worsening situation contributed to O’Neill’s resignation in April 1969.

BBC News: Police break up NICRA civil rights march in Derry (October 1968)

Taoiseach Jack Lynch on the causes of the unrest in Derry (October 1968)

Terence O’Neill: “Ulster stands at the crossroads” (December 1968)

Bernadette Devlin on the Loyalist ambush at Burntollet (January 1969)

Terence O’Neill calls for an end to marches and violence (January 1969)

A joint communique on reforms in Northern Ireland (March 1969)

© Alpha History 2017. Content on this page may not be republished or distributed without our express permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use.

This page was written by Rebekah Poole and Jennifer Llewellyn. To reference this page, use the following citation:

R. Poole and J. Llewellyn, “From civil rights to civil unrest”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/civil-rights-to-civil-unrest/